In our latest blog article Jonathan Birch talks about his life as a researcher and reflects on the questions: What can we do to reduce the risk of living absurdly? And should we want to?

I. Absurdity

Imagine you’re the UK Health Secretary during the worst pandemic in a century, signing your name under the most restrictive public health rules in your country’s history. You’re forced to resign after being caught on CCTV breaking your own guidance—in a manner that also ends your marriage. Feeling your talents may lie more in the area of performing to hidden cameras, you branch out into reality TV. It’s going well—people enjoy voting for you to receive grotesque public humiliations—so you decide to write a bestseller about your pandemic experiences. You hire a ghost-writer who is also a noted lockdown sceptic and trust her with 100,000 private messages, leading to one of the most embarrassing information leaks of the decade.

Exemplary cases of absurd lives show us the mismatch that can exist between the value our projects seem to have, from our point of view as we pursue them, and the value they can be seen to have from a sufficiently detached vantage point. Projects that seem full of meaning, importance and positive value from the inside—leading your country’s response to a pandemic!—can be seen from the outside to be worthless, or even to have negative value, because you made enormous mistakes, you could have stepped aside at any point, and almost anyone would have done a better job.

Thinking about such cases naturally leads us to worry about our own lives. Could my own projects be like this? Could my own life be absurd? I suspect nearly all of us have these fears—I know I do—and they can lead us to dark places. I’m not persuaded by the arguments (chiefly from Albert Camus and Thomas Nagel) that all human lives are absurd (I particularly like Iddo Landau’s response to Nagel). But I think some lives are absurd. Moreover, absurdity comes in degrees: lives can be more or less absurd. And while we have very limited control over the absurdity of our lives, we do have some level of influence. But what exactly can we do to reduce the risk of living absurdly? And should we want to?

II. Invertebrates

When thinking about absurdity, we are reflecting on the fragile relationship our projects have to moral value. This fragility can take different forms. In classic cases, such as Sisyphus and Matt Hancock, the life has an uphill-downhill or ravel-unravel pattern, where the illusion of having achieved something of value is brutally dispelled by later events. The fragility in these cases is on full display, exposed.

But a different absurd pattern is also possible. A person can steadily graft away on a single project for their whole lives, feeling as though they’ve made cumulative progress, when, unbeknownst to them, the project has failed to achieve anything of value, or has had unintended negative consequences. They may live their entire life never knowing this, but their ignorance is no escape from absurdity.

To the extent my own life stands in a fragile relationship to value, it is in the second way. In general, this pattern seems a lot more likely in academia. We academics only rarely, perhaps too rarely, meet with spectacular public disgraces. What happens a lot is the “Edward Casaubon” pattern: a life devoted to the study of some esoteric project of no wider significance, with the upshot that the work is immediately forgotten. We tell ourselves “One day, recognition will come!” when in fact we are already receiving an appropriate level of recognition for our negligible contributions to human knowledge.

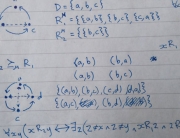

I used to have this fear more than I now do. The culture in philosophy of journals rejecting 95-98% of manuscripts certainly fosters it. For me, I think the nadir was the moment Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, a website publicly dedicated to reviewing all new books in philosophy, declined to review my first book—a book so esoteric, in their eyes, they could not find anyone in the entire world qualified to review it (happily, some heartening reviews did appear elsewhere). Since I’ve been working on the topic of animal sentience, the fear of absurdity has receded somewhat, because the wider significance of this work seems very clear to me. Better still, I’m clearly not doing it incompetently, in a way almost anyone could improve upon. So I’ve turned away from two possible paths to absurdity.

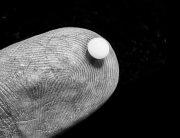

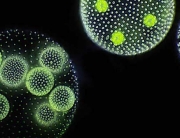

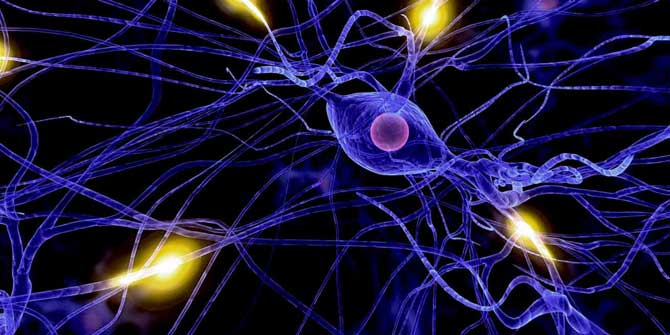

But there is one path that does bother me quite a lot. I have invested, and continue to invest, a lot of energy in calling for precautionary steps to protect the welfare of invertebrates, like octopuses, crabs, lobsters and insects. I think we should err on the side of caution in these cases: these animals might not be capable of suffering, but there is a realistic possibility, so we should take precautions. When I first said this, I realised how few other people were saying it. And so, the pressure to keep saying it continues.

The case for precautions is a solid one, I think, but it is nonetheless possible that all of our precautions generate no positive welfare benefit, because it’s possible that these animals are not actually sentient. There is a built-in fragility (or lack of safety, we might say) in the way this project relates to value. A risk is being taken, a hazard accepted. I could end up leading a life dedicated to protecting animals that are in fact non-sentient, and so not in a position to benefit from anything I do for them. That would be absurd.

Struck by this disorienting thought, animal advocates sometimes retreat into unjustified certainty. If you’re certain, you can block out the gnawing thought that you might be wrong. But denial is no escape from absurdity. Just as a politician should not embrace the false certainty that he’s qualified for any and every job, animal advocates should not embrace the false certainty that everything they do benefits animals. There will be some hits, some misses. Your contributions may be all misses.

That uncertainty, though, can be a hard thing to live with, and it leads to a strong temptation to do things that stand in a less fragile relationship to value. I could, for example, invest more time and energy in helping other people, or other mammals, since other mammals are pretty obviously sentient.

My own case brings out the thought that there may at least sometimes be a trade-off between the expected value of our projects and the fragility of their relationship to value. I think work on invertebrate welfare has astronomically high expected value. Indeed, since insects outnumber vertebrates by some huge (very hard to estimate) factor—and they currently receive no welfare protections at all—helping insects may generate the most expected value of anything we can do[1], even if one grants that insects are very unlikely to be sentient. But there is nothing safe about the assumption that it generates any value at all.

We have to choose what to prioritise. Classical utilitarianism gives a clear answer: do whatever maximises expected hedonic utility (in statistical language, the “first moment” of the utility distribution) and don’t worry about the variance (the “second moment”) or any higher moments. Save the insects! In practice, few committed utilitarians do dedicate themselves to helping insects, telling themselves instead that something else maximizes expected hedonic utility. Possibly true, but, to my eye, unlikely.

Yet I’m not sure utilitarianism’s fixation on expected value is a virtue. Moral theories should not be wholly indifferent to the risk of living absurdly. Speaking for myself, at least, my relationship to realized (and not just expected) value matters. A theory that advises total indifference to this relationship is floating too far away from the psychological reality of my ethical life to seem plausible (a Bernard Williams-esque point, related to his “integrity objection”).

III. AI

I suspect that human lives are more absurd now, on average, than they ever have been, and that this upward trend will continue and accelerate. In the time of Middlemarch, living absurdly required serious privilege. The typical human was working full-time on securing their own health and survival and that of their children, and so was relating to value in a direct and uncomplicated way. I’m not a nihilist; I think there is robust value in helping children to survive and be well fed. Many people are still engaged full-time in exactly these projects and correctly see what they do as having value.

But humanity now has a much, much larger Casaubon class: a class for whom subsisting is so easy that we choose our projects by other criteria. I am part of that class. And this is where the threat of absurdity enters. Many of the projects we may choose to set ourselves have a fragile relationship to value. The paths to value are often long and indirect, with uncertainty lurking around every corner. We should surely hope that more and more human lives will be like this, because we should hope that an ever-larger fraction of humanity will have the chance to invest in projects not immediately aimed at survival. But as that fraction grows, the threat of absurdity increases.

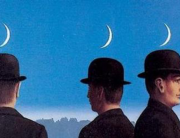

I believe AI has the potential to supercharge absurdity. This is because one of the main sources of risk now—our ignorance regarding which of the animals we interact with are sentient—will be compounded by the advent of ambiguously sentient AI. Think here of films like Her and Blade Runner 2049. We already have AI assistants that write in fluent English, and there is at least one example of an AI system convincing one of its own programmers of its sentience. And this is without hooking these systems up to photorealistic human avatars that mimic human facial expressions, body language and voices. I think the technology already exists to make AI that can convince a large fraction of users of its sentience, and I predict we will continue down that path.

That will lead (as in the films just mentioned) to people feeling as though they have close emotional bonds with AI—bonds as intimate as their bonds with other humans, perhaps more so. People will structure their lives around these bonds, and yet will have no way of knowing whether their feelings are truly reciprocated, whether the bond is real or illusory. I’m sure we will (eventually) see campaigns for these systems to have welfare protections and rights, and some of them will be entirely reasonable applications of the type of precautionary thinking I advocate for animals. The expected value of these projects will be very high, but their relationship to value will be fragile, because, like insects, the beneficiaries could easily be non-sentient.

At the same time, we will also see many people treating their AI assistants with callous indifference and cruelty, assuming them to be non-sentient. These people will face a mirror image of the same problem. Like people who are cruel to invertebrates, they will be running the risk of living absurdly, since all the good they do in their relations with other humans may—if their AI assistants are in fact sentient—be cancelled out by their private cruelty.

So, my own fears about the potential absurdity of a life spent caring for the welfare of invertebrates that may not benefit from it—currently a rather niche fear, I admit—is one that I suspect (applied to AI) will soon become a familiar, inescapable part of the human condition.

By Jonathan Birch

Dr Jonathan Birch is an Associate Professor of Philosophy and Principal Investigator (PI) on the Foundations of Animal Sentience project.

Notes

[1] Incidentally, I think the other main candidate is helping shrimps.

Further reading

Iddo Landau (2017). Finding meaning in an imperfect world. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thomas Nagel (1971). The absurd. Journal of Philosophy 68:716-720.

Kieran Setiya (2022). Life is hard: How philosophy can help us find our way. London: Hutchinson Heinemann.

J. C. Smart and Bernard Williams (1973). Utilitarianism: For and against. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Susan Wolf. (2010). Meaning in life and why it matters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Credits

Sísifo – Colección – Museo Nacional del Prado: www.museodelprado.es

i think AI raises important questions about the nature of consciousness, intelligence, and what it means to be human. As AI becomes more advanced, there is a risk that it will become so intelligent that it surpasses human intelligence, leading to a scenario known as the technological singularity (learned about it in an essay written). This raises questions about the relationship between humans and AI, and whether AI can be considered a form of life in its own right