We are happy to share a very special blog post by Ariana Razavi, winner of our LSE Philosophy Peace Prize 2023.

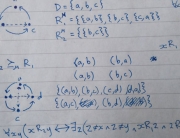

Introduction by Professor Jonathan Birch: It’s a pleasure to introduce winner of the LSE Philosophy Peace Prize, Ariana Razavi. The aim of the competition was to encourage students to reflect, in the form of a blog post, on how philosophy can help promote peace. Ariana Razavi’s winning entry thoughtfully discusses two epistemic conditions for peace at the core of Kant’s project in his 1795 essay, “Perpetual Peace”: knowledge of a universal human nature and knowledge of cosmopolitan connectedness. The piece takes a distinctive view on a topic that is usually approached through the lens of normative ethics rather than epistemology. I fully agree that many areas of philosophy—including epistemology—are relevant to the question of how to build a peaceful world.

What would it take to build a peaceful world? This is undoubtedly, in part, a political question; one that has been primarily attempted to be understood through a political lens and actualised through political means. But like many political questions, and social phenomena more broadly, examining the underpinnings of peace may reveal that it has epistemic foundations. In other words, there may be knowledge conditions for global peace, not just political conditions.

In recent weeks, I have found myself revisiting Kant’s Perpetual Peace – perhaps because of my Middle Eastern origin, perhaps simply in search of solace. And from this reading, I have been attempting to extrapolate some potential knowledge conditions, the fostering of which may be able to give a glimpse of a path to peace – initially on a smaller scale than Kant envisioned, perhaps, but peace nonetheless.

In Kant’s political writings, the idea of peace and a cosmopolitan view of social organisation – broadly, that there should exist a global community that overrides smaller-scale boundaries – are fundamentally inseparable. This leads to the thought that the epistemic foundations of peace may be closely related to the epistemic foundations of cosmopolitanism. In this short piece, drawing primarily on Perpetual Peace, I will explore two knowledge conditions for peace that are, at some level, intertwined.

Let us begin with the first knowledge condition – knowledge of a universal human nature, or of an overarching human identity. This concerns the conscious recognition that there exists something inherent to humanity that is shared across all human beings. Identifying some such common feature is a critical foundation for peace, an idea implicit in Perpetual Peace.

Thinking in the Kantian framework, the essentially human quality involves the capacity for reason, which is directly linked with the capacity for morality. An acute awareness and enduring consciousness of these human capabilities affect how we cognitively perceive other human beings: that is, primarily as beings with a similar nature to that of our own. This view, that Kant endorsed, was contra the “polygenist” narrative, held by many of his contemporaries, that different races were different species – thereby blocking the very notion of a shared sense of humanity. Perpetual Peace serves as an explicit departure from both this widespread historical view as well as from his previous views on the subsidiary status of non-white races.

This knowledge of a universal human nature is crucial to foster a conception of human identity, an inherent link between each individual and every other individual, that is strong enough so as to make nationality subsidiary to our common humanity. This is implicit in Kant’s idea of a ‘Cosmopolitan Right’ which refers to the right each human being has to visit every region of the earth, and is a ‘means for social intercourse’ – in other words, an ‘attempt to form community with all’ (a phrasing I particularly like, borrowed from Kant’s Metaphysics of Morals).

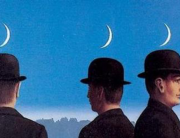

The second epistemic condition for peace, then, is knowledge of cosmopolitan connectedness. This is a condition extrapolated from the following passage from Perpetual Peace, referring again to the Cosmopolitan Right, which entails ‘the common possession of the surface of the earth, to no part of which anyone had originally more right than another; and upon which, from its being a globe, they cannot scatter themselves to infinite distances, but must at last bear to live side by side with each other.’

What I glean from this passage, ultimately, is the underlying fact that we as humanity share the ‘surface of the earth’; we have a common possession of the world. This fundamentally connects us all, not only as joint holders of a common human nature, but also as joint stewards of a common physical world. It further diminishes the significance of national boundaries and fosters a knowledge of connectedness to other parts of the world, to those living differently from us. For Kant, this finds expression in a ‘universal republic’, a world commonwealth, which at its core serves to undermine national identity, thereby emphasising the common human identity – the importance of which we have established.

While examining Kant’s Perpetual Peace and the general epistemic underpinning of social and political phenomena is a timeless exercise, identifying, considering, and fostering the knowledge conditions that might assist with the creation of peace feels at the present moment more pressing than ever. I have come to realise, perhaps through writing this piece, that my Middle Eastern background should not have such a bearing on my urgent desire for peace – rather, instead, my humanity should.

By Ariana Razavi

Ariana Razavi is a student in the MSc Philosophy and Public Policy Programme at LSE Philosophy.

Further reading

Appiah, Kwame Anthony “Cosmopolitan Patriots” in Critical Inquiry 23/3, 2017, pp. 617-639. Available at: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/epdf/10.1086/448846

Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace. Translated by Jonathan Bennett, 2017. Available at: earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/kant1795.pdf

Kleingeld, Pauline and Eric Brown, “Cosmopolitanism” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2019, Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Available at: plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/cosmopolitanism

Kleingeld, Pauline “Kant’s Cosmopolitan Law: World Citizenship for a Global Order” in Kantian Review 2, 1998 , pp. 72-90. Available at: cambridge.org/core/journals/kantian-review/article/abs/kants-cosmopolitan-law-world-citizenship-for-a-global-order/485D8C4742BFFF5DC7664F109463B9CC

Connect with us

Facebook

Twitter

Youtube

Flickr