Liam Kofi Bright, currently at Carnegie Mellon University, joins LSE Philosophy in September. We thought we’d celebrate his imminent arrival with some questions.

Q: Firstly, can you tell us a little bit about your philosophical background and interests, and about what brought you to LSE Philosophy?

A: My experience of philosophy begins when I was growing up in South London, long before I entered university. Since my parents were committed socialists we often discussed current events around the dinner table, focussing on their moral and political significance in light of wider history. What’s more, we had a number of philosophical books lying around at home. As a teenager I remember reading and being deeply moved by CLR James’ The Black Jacobins, Machiavelli’s The Prince, and Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. I did not always, mind you, come away with the most sophisticated understanding of the material. I think at one point I read St Thomas More’s Utopia and started seriously wondering whether we could divide up the nation’s sheep in the way More suggested! This latter work also connected to my Catholic faith; Catholicism raises its own philosophical questions, which in the glorious early days of web 2.0 I would argue about on internet forums. I also went out of my way to find philosophical texts to read. Probably the most revealing story I can share in this context is that my personal form of teenage rebellion consisted of telling my dad I was going to the library to revise for exams, but then actually reading St Augustine’s Confessions and Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling along with various works of science fiction… if you’re reading this – sorry dad! (This also speaks to how well stocked my local public library was.) Finally, my 6th form college also, thankfully, offered a philosophy AS level for me to take. So by the time I was applying to university I was pretty set on studying philosophy, though at that point the thought hadn’t entered my mind that philosophy was the sort of thing one could do for a living.

It was when I was pursuing my undergraduate philosophy degree at Warwick (I believe the LSE had rejected me!) that it first struck me that I could be a professional philosopher. Due to a close relationship with the resident logician, Walter Dean, I had developed an interest in mathematical philosophy. I hoped to do a PhD in philosophical logic, and had apparently got into Melbourne when a series of unfortunate events intervened and prevented me from attending. In the face of this set back I somewhat naively concluded that that was the end of my hopes of being a philosopher, and set about looking for work outside the academy. This was 2010, with the crash a very recent memory, so the market wasn’t great – I ended up working as an accountant in a prison. I really didn’t like the job one little bit, in part (but only in part) because it was so dull. Word reached me through the grapevine that one of my professors from Warwick – Kai Spiekermann – had moved to London to take up a post in the LSE’s Government Department, so I reached out to him via email to ask if he knew of any intellectual activities I could take part in around London. He recommended that I attend meetings of LSE’s Choice Group, so I did, and was reminded of how much I loved the discussions and debates of abstract philosophy. On the basis of this experience I ended up pursuing and receiving a scholarship to obtain an MSc in the Philosophy of Science in the LSE philosophy department.

With this in hand I went off to the states to do a PhD at Carnegie Mellon. The atmosphere at CMU is pretty similar to that at LSE. In both departments people have aspirations to use mathematical tools to engage with scientific and social issues of philosophical interest. Personally, after conversation with my now-advisor Kevin Zollman, I became especially interested in using the tools of game and decision theory to study the social epistemology of science, which means I focus on understanding the social institutions of science and how they affect our ability to produce and disseminate knowledge. So, in a way, this represents a pleasingly Hegelian synthesis of my journey – from the very applied socio-political interest of my youth, passing into very abstract mathematical interests upon being introduced to university philosophy, with the tension resolved by using mathematical tools to study social arrangements. After I finish up this PhD it will be back to the LSE to take up an Assistant Professor’s position, which is a lovely role for me. For one thing, it will allow me to return to my home town… that is, if one counts anything north of the river as really in the same town. But for another, it is nice to return to an institution where I know the departmental culture is really aligned with my own interests and values.

Q: Can you tell us a bit more about your interest in social epistemology and about the role of philosophy in understanding the social structure of science?

A: I’m interested in social epistemology just because I find its questions fascinating, and believe them to be important in a world where science is such a large and influential social endeavour. As to what philosophy contributes, that is an interesting question in itself. Many fields are involved in the study of science and its institutional workings – history and sociology especially, but one can also find psychologists, economists, anthropologists, and mathematicians and statisticians, writing detailed and insightful works on the social structure of science. Seeing how these various inquiries can be drawn together and amalgamated is itself intriguing, and I have gained much insight into the workings of science, as well as wonderful intellectual collaborators, through the kind of interdisciplinary contact fostered by social epistemology.

As far as philosophy goes, social epistemology is unusually open to applied research. Often in philosophy it is perceived as rather low prestige to directly concern oneself with policy proposals or practical affairs. But in social epistemology it has never been the case that we aim only to interpret science, there is always an eye to changing it. This is in part because a lot of the work from people in other fields studying science is centered around proposals to make science work more ethically or efficiently. For instance, there are ongoing projects to see what effects various funding regimes have had on encouraging humane and innovative work, or to see what effects different peer review systems have on the reproducibility of published research. This naturally draws us into the activity of formulating and evaluating policy proposals for the improvement of science. Making good policy proposals involves not just understanding the facts on the ground, though that is vital. One also needs a good grasp of relevant normative principles, and when one is considering potential policies one needs the tools and skills available to reason in a disciplined fashion about ways the world is-not-but-might-be. A philosophical education involves much more emphasis on normative theory (in both ethics and epistemology) than other fields will typically provide. What is more, reasoning is especially fraught when one seeks to connect claims about what is to claims about what ought be, and so the kind of logical fastidiousness that philosophical training encourages can be useful. Our training in the production and evaluation of normative argumentation is thus especially useful in a field so centered around policy proposals for the betterment of science.

I think social epistemologists also have something distinctive to contribute to philosophy of science more broadly. Philosophers of science have long been interested in providing conceptual analyses of core notions in scientific practice, and trying to see how they fit into an overall theory of what it takes for inquiry to go well. This leads us to ask questions like: how is it that scientific theories can successfully explain the phenomena we observe?, and what kind of relationship does data have to bear to theory in order that it may rightly be said to confirm that theory? Studying the social institutions and practices of science and scientists brings to the forefront some under-explored notions which then raise questions that are similar in spirit to those just mentioned. So in social epistemology of science we ask such questions as: how can multiple streams of data be amalgamated to form a coherent evidence base, and what happens when the teams who produced the original data had quite different presuppositions and working methodologies? Should prestige or social standing play such a large role in the organisation of science, or is the drive for social esteem making our inquiry less reliable? Relatedly, how can we best promote honesty by scientists even when they have incentives to be dishonest? Data amalgamation, scientific credit, and scientific honesty are all issues which gain their importance from the fact that science is a social enterprise, and the full complexities of these issues has only been made clear to us by working with other scholars of science. The traditional questions of philosophy of science are pertinent to these problems, and can themselves be better understood with these in mind. For instance, social epistemologists of science, especially those working in the feminist tradition, have done a lot to help us understand how the presence of methodological and theoretical diversity in science contributes to our ability to confirm theories and hypotheses.

Q: Can you tell us about your interest in Africana philosophy and the work of W. E. B. Du Bois?

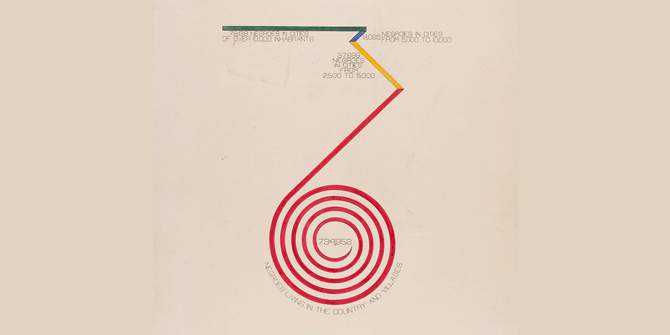

A: A large part of how I came into philosophy was through works in what I would now recognise as the Africana tradition. It is hard to define precisely what this tradition is, and in particular there has been some meta-philosophical dispute as to whether Africana philosophy is philosophy produced by folk from the African continent and diaspora, or work that is somehow especially concerned with the experiences of African people (inclusive of the diaspora) but not necessarily produced by people of recent African descent themselves. I will not attempt to settle this here, though I recommend interested readers check out this podcast series, because in my case work that would meet either definition has been formative for me. Black Jacobins especially encouraged me to think that there was much to be learned by studying the political experience of the African diaspora, and how our thinkers have reflected on that experience. Anyone working their way through the Africana intellectual tradition will eventually discover W. E .B. Du Bois, and when I finally did I was immediately inspired. Here was somebody interested in the political experience of the African diaspora, who developed theories of democratic government attuned to this, but also used the tools of quantitative social science to study social life, and engaged in philosophically sophisticated reflections on his own methods of study. His interests very much mirrored my own, and due to his skill in developing his ideas I’ve found that responding to him – even, perhaps especially, where I disagree – has been incredibly fruitful for me. For what it is worth, this post’s featured image is an example from some of his innovative work in data visualisation, a nice discussion of which can be found here.

For instance, Du Bois seems to me one of the clearest thinkers on the relationship between the social organisastion of science, its position in a democracy, and the kind of methodological or epistemological consequences this ought to have. Over the years he developed a sustained argument in favour of what philosophers now call the value free ideal, which is roughly the idea that scientists should not be influenced by non-epistemic values in key aspects of their work. Philosophers of science nowadays largely reject the value free ideal, so thinking through Du Bois’ reasons in its favour helps challenge what may otherwise become merely received wisdom. It also helps illuminate the broader social significance of this debate in ways that are nowadays not as often appreciated. (It’s worth noting that, what is more, later in his life when he changed his mind on this score, Du Bois anticipated the inductive risk argument, which is now taken by many to be the decisive argument against the value free ideal!)

While I will continue to work through Du Bois’ philosophy, it should be noted that he is not the only Africana philosopher that I would encourage others to seek out. To name just two more by way of illustration, I have found that Ida B. Wells‘ stark illustrations of human evil, arguments concerning the meaning and importance of genuine rule of law, and methodological practices in carrying out social research, are all deep wells of philosophical insight. The Ghanaian philosopher Kwasi Wiredu is also a far ranging thinker whose work defies easy summary, but suffice it to say that I have found much of value in his ideas about truth and meaning, the role of consensus in democratic politics, and what the project of decolonisation really entails. The Africana tradition in philosophy is under-appreciated, and students will find many novel ideas and arguments of great value if they take the time to actually explore what it has to offer.

Q: Can your work on the social epistemology of science be applied to professional philosophy itself, and particularly to the under-representation of Africana philosophy/philosophers?

A: Plenty of the work I have done involves studying institutions and cultural features of science that are shared with professional philosophy. After all, many scientists and philosophers are working in the same sort of academic environment. So, for instance, I have studied whether or not scientists seeking professional glory encourages more fraud than would be found if scientists were concerned only to let the truth be known through their publications. In my work on this I looked mainly at debates about the role of the journal publication system in setting scientific standards. Where at one point I drew upon a case study it was from the history of biology. But philosophers just as much as scientists are concerned about their reputations, and likewise can be concerned to see the truth known about their topic matter of interest. So, my suspicion is that in so far as my argument was successful in the case of science it should likewise go for professional philosophers. I use this example from my own work in part because I first got thinking about how to understand fraud in science by wondering whether or not philosophers might fake the results of their thought experiments, as was suggested in jest here. So this is a case where I began by wondering about professional philosophy, was moved by this to examine the sociological literature on fraud in scientific practice, and eventually produced an argument which I believe should go as well for philosophy as science. Our common institutional setting induces social-epistemic similarities between philosophy and science, despite the cultural or methodological differences between us.

In general, I am less confident my work has much to say about why it is Africana philosophy and philosophers are under-represented in professional philosophy. If my work is relevant to this topic it would be by way of some quite indirect chain of reasoning. However, I suspect that the under-representation of Africana philosophy and philosophers does not have an informative and philosophy-specific explanation. Mainly it is black folk doing Africana philosophy. One does not tend to find many black folk in high prestige professions in the UK or USA, and professional philosophy is no exception to this general rule. Relatedly, activities which are culturally coded as black tend to be perceived as low prestige by the rest of society. Again, Africana philosophy is no exception. So I suspect that explaining why there are not many people doing Africana philosophy in the profession would reduce to the general social questions of why there are not many black folk in high prestige professions, and why people perceive the kind of things that black people do to be low prestige. These are deep and difficult historical and sociological questions. I would advise that people read Charles Mills’ The Racial Contract as a good place to begin in answering them.

I think I have done more work in the other direction, using Africana philosophy to explore topics in social epistemology and philosophy of science! My work on fraud mentioned above, for instance, is related to my work on Du Bois’ philosophy of science. I (along with coauthors) have also drawn heavily upon Du Bois’ scientific work in a paper that gives a defence of multi-methods approaches to the social sciences. I (again along with coauthors) also have a paper on causal reasoning that is based upon the work of Crenshaw and others from the black feminist tradition. On my more optimistic days I hope that by such work as this I might convince people to give Africana philosophy more of their attention, and thus indirectly encourage more people to themselves become Africana philosophers.

Q: Finally, what do you think is the relevance of philosophy?

A: If all has gone to plan, my previous answers have gone some way to addressing this! Social epistemology of science can help scientists organise their activities to better achieve their goals, and reflect on the desirability of those goals themselves. This is because philosophical training teaches some of the skills necessary to responsibly consider normative questions, and evaluate arguments that are put forward in favour of various schemes and ideals. Evaluating arguments and responsibly considering questions about what we ought to do is useful more generally. This is not just for the particular questions facing science policy makers. Faced as we are with a barrage of claims from well meaning idealists and cynical hucksters alike, this is a highly relevant skill set for any citizen in a democracy who would take part in their own government. We in philosophy can hence do our research and teaching with the goal in mind of aiding people in navigating the epistemically and ethically complex waters of our shared challenges. I should note that this is drawing on Kristie Dotson’s conception of philosophy from a position of service, which is the idea that we as philosophers do our work in order to make our knowledge and skills available to people whose projects we wish to aid or advance. I see a lot of what we do in philosophy as in service to the projects of various institutions of democratic society, and the citizens who inhabit those institutions.

I also spoke above about the role of Augustine et al in my youth. That they played this role was not, I think, all that idiosyncratic to me. As far as I can tell there has never been a society on earth which did not set aside some of its time and resources to considering questions about the nature of the universe we inhabit, or the ethical duties which confronted its members or itself as a corporate body. At the least, there are always some people who see some good in considering these questions and reflecting on the various answers that might be offered to them. Philosophy thus seems to be one of those basic cultural goods which many people value for its own sake. Its production is thus akin to art or sport in its worth to those who choose to engage with it. Just as it is a worthy social goal to give more people more opportunity to encounter and participate in the arts, or more opportunity for leisure and play, so too it is a basic and self-justifying goal to give more people access to philosophy, as something intrinsically valuable that might enrich their lives. Seen from this perspective, where philosophy is one of life’s simple pleasures, it is rather odd to wonder about philosophy’s relevance. Relevance to what? One may just as well ask: what is the relevance of eating shortbread biscuits with tea? Despite the eternally breathless Crisis of the Humanities articles one constantly sees in the press, I have never worried that ours will be the first society in all of history to simply stop engaging in these kind of valuable activities. The only real question is how we shall distribute access to these cultural goods. I hope to live in a society that equitably extends the possibility of partaking in the joys and consolations of philosophy.

Liam Kofi Bright is a PhD student in philosophy, currently studying at Carnegie Mellon University. He works on the philosophy of science and social epistemology. He’s looking forward to returning to his native London this autumn to start his role as an assistant professor at the London School of Economics, working in the department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method.

Featured image: Public Domain, cropped from the original

Really interesting interview and I thought your segment on Chike Jeffers and Peter Adamson’s podcast was great, e.g. really clear. And though I have immense admiration for Dubois I think I go with the modern philosophers of science re. the possibility of value neutral science (even though as a physicist slogging it out in the salt mines I desperately wanted to believe in it !). I look forward to checking out some of your work.