How do you hope to be thought of after you die? In his final post in this series, Luc Bovens looks at attitudes towards the dead.

People hope that others will hold certain attitudes towards them when they are gone. They hope to be missed, remembered and respected. There is some overlap between these categories. If one is missed, then one is being remembered. The fallen in a war are not respected unless they are remembered. But nonetheless, these attitudes are different. One may be remembered without being missed. One may be remembered without being respected or missed. Each of these attitudes is problematic and stands in an interesting tension with some of the hopes that we have discussed earlier. We will take up each in turn.

Being missed

The hope to be missed by loved ones is a curious hope. Grief is a powerful emotion that can deeply mar one’s life. “Parting is all we know of heaven – And all we need of hell,” writes Dickinson. Why would we hope for anything like this from our loved ones, especially considering that our hopes for the future typically include that they will do well.

Why would we want to be missed at all? When you leave a job you may hope that the company will fall apart without you. This may play into your sense of self-importance. It may be a kind of revenge: you feel that you were not respected and now they get what they deserve. But these are sad hopes, if not shameful hopes. Some such hopes may enter in at the end of life as well. I remember an obituary stating that it was the wish of the deceased that there be no meal after the funeral, since “people have had plenty of time to come and have a meal with me, I would have been more than happy to oblige, but nobody ever came.” People feel slighted in life and hope that they will be missed in death – and preferably missed with guilt-laden grief.

But is there not a healthy way of hoping to be missed?

Being missed, one might say, is a sign of being loved. And we hope that we were loved. This is a good explanation when we are uncertain of being loved. But what if we are confident that we are being loved? Why hope for the smoke when we know that there is fire anyway?

Being missed, one might say, is part and parcel of being loved. And so in hoping to be missed we are not hoping for a sign of being loved, we are simply hoping to be loved. It is still a strange thing to hope for. We don’t need to hope for everything that is part and parcel of the things we hope for. Academic job applicants hope to get jobs in academia, but they don’t hope for the piles of grading that is part and parcel of such jobs. World travellers hope for pristine beaches, breath-taking sights, and novel experiences, but they don’t hope for the long plane rides that are part and parcel of world travel. So why, in hoping to be loved, do we need to hope to be missed?

Furthermore, being missed need not even be a sure-proof sign of being loved or part and parcel of being loved. People love in different ways and they love different people in different ways. Grief after loss need not be a measure of love that once was. There is love that is able to let go and that barely grieves. There is a grief that is intense, not because of love for the deceased, but because it is intermingled with many other more and less healthy emotions.

By Wendy / CC BY-SA 2.0 (colour edited from original)

So, what would be wholesome hope in the way of future attitudes from loved ones? There is much wisdom in Christina Rossetti’s poem “Song”:

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing not sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

Rossetti asks that there be no expressions of grief upon her death from a lover. But she hopes that he will be like the grass on her grave – keeping a connection but standing strong and directed toward the world. Whether this is enhanced by missing her or not is of no import. The most we should hope for is that a kind of connection remains, which can find expression in a feeling of absence, but this feeling should be a feeling that enriches life. In other words, let us hope to be missed, just a little bit.

Being remembered

The hope to be remembered is close to the hope to make an enduring contribution. But it’s not the same thing. Here are a few questions to ponder.

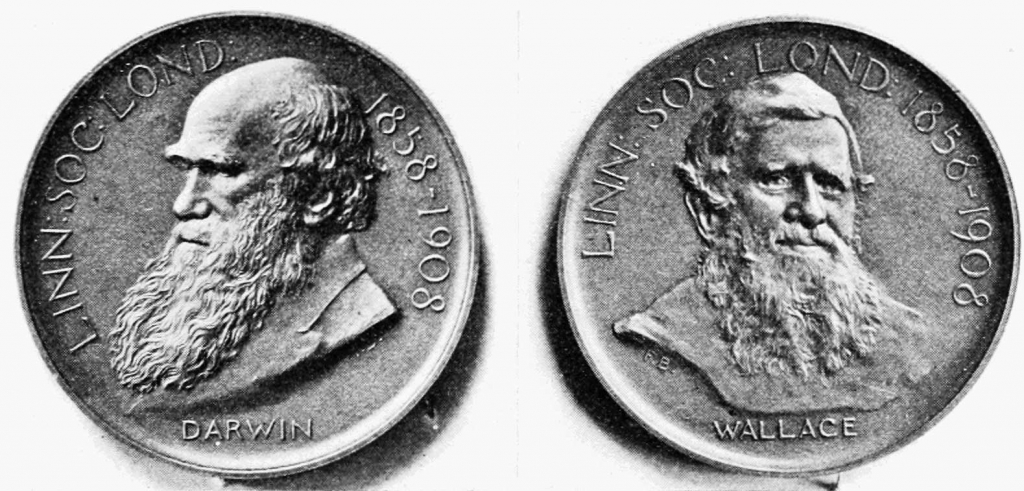

Both Alfred Russell Wallace and Charles Darwin came up with the core ideas of the theory of evolution at roughly the same time. Now suppose Wallace’s work did more for the theory of evolution than Darwin’s work, but Darwin is certainly more remembered than Wallace. Would you prefer to be Wallace or Darwin?

Suppose that you are Shakespeare on his death bed. A genie in a bottle gives you a choice. Either all of your work will remain preserved for posterity but the identity of the author will be forgotten and each of the plays will be signed off as “Anonymous”. Call this Shakespeare Anonymised. Or, half of your works will be preserved with your name properly attached to it, while the others will be lost forever. To make it harder, suppose that 90 per cent will be. Call this Shakespeare Redux. What would you choose?

If you only hope that your life is worthwhile on grounds of having made enduring contributions, then you should choose to be Wallace and you should choose to be Shakespeare Anonymised. If you choose to be Darwin or Shakespeare Redux, then you also hope that you will be remembered, over and above the hope of having made an enduring contribution.

The 1908 Darwin Wallace medal of the Linnaean Society.

Public Domain.

Why would one want to be remembered? We may think of ourselves as getting some kind of lease on life when our names live on in people’s minds and continue to be mentioned in conversations and written work. There is something very odd about this sentiment and Woody Allen appropriately mocks it: “I do not want to achieve immortality through my work, I want to achieve immortality by not dying. I don’t want to live on in the hearts of my countrymen, I want to live on in my apartment.”

Presumably we don’t just want to be remembered, we want to be remembered well, just as we want people to think well of us during our lives. What good does being thought of well do? During one’s life it matters because people will trust you and this provides for opportunities. But being remembered after one’s death does not provide any such benefits. It matters to be thought of well because it provides some limited evidence that one’s contributions are worthwhile. Sure, but why not just hope that one’s contributions are worthwhile? There is no point hoping for smoke when you can hope for fire.

So we need to give a different answer. Many people value being thought of well in itself. It is not of value because it provides opportunities or because it provides evidence. It is of value for what it is and that’s that. It is reasonable to think that being remembered posthumously has the same appeal.

And so a desire to be thought of well posthumously might make one hope to be Darwin rather than Wallace and Shakespeare Redux rather than Shakespeare Anonymised. It wouldn’t be my choice, but it is not a crazy choice.

Being respected

Diogenes asked that his corpse be set out to be devoured by the wild animals. Jeremy Bentham had his body embalmed and put on display in UCL. King’s College students stole the head in 1975 (and returned it) and there is a legend that it was used for an impromptu game of soccer.

Most people are not like Diogenes and they would rather not see their heads used as soccer balls. They hope that their bodies, bones, or grave sites will be treated with respect after they are gone. We are horrified when we hear reports of the corpses of US soldiers that were dragged through town in Mogadishu, the severed heads being displayed by ISIS, people urinating on graves, desecrating Jewish graveyards with swastikas etc.

There is an interesting tension at the heart of photojournalism that flares up regularly. It is an unwritten rule that there should be no frontal shots of corpses out of respect for the deceased as well as their loved ones. But the picture that shows a frontal shot is often so powerful that it has the potential to bring about social change – more so than more respectful pictures shot from other angles. And this puts photojournalists and newspaper editorial boards into a bind.

The picture of Alan Kurdi, the Syrian toddler whose corpse was washed ashore on 2 September 2015 in Turkey, was a case in point. There were two pictures – one shot in which he is washed up on the beach with his face toward the camera and one in which he is being carried away by an aid worker with his face hidden. Newspaper were split on which picture they should publish. Some refused to publish the frontal shot out of respect for the little boy and his family, but it was precisely this picture that affected public opinion and made a difference to worldwide refugee policy.

Larry Burrows, a photojournalist who was killed in Vietnam, puts the choice as a choice between “capitalizing on other people’s grief” and “penetrating the hearts at home of those who are simply too indifferent.” Burrows phrases the choice between respect for the loved ones of the deceased and affecting public opinion. One could also frame the conflict as a conflict between presumed hopes of the deceased. We may presume that the deceased have a hope that they will be respected which includes respect for the corpse. They may also have a hope that their death not be in vain – that it will do some good for causes that they believe in. And one would need to assess what is more important in particular cases.

Summing up, we have hopes that others will bear certain attitudes toward us when we are no more. Hoping to be missed stands in a tension with the hopes that our loved ones’ lives will not be marred by grief. Hoping to be remembered is subtly distinct from hoping for a worthwhile life on grounds of having made enduring achievements. And there is an interesting tension between meeting the deceased’s hope to be respected in death and the hope that one’s death may lead to some good.

By Luc Bovens

← The Last Hope Part 2

Luc Bovens is is currently Professor in the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method and will be moving to the Department of Philosophy in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in January 2018. His areas of research are moral psychology, philosophy of public policy, rationality, and formal epistemology.

Further Reading

- Luc Bovens “Secular Hopes in the Face of Death” In Rochelle Green (ed.) Theories of Hope: Exploring Alternative Affective Dimensions of Human Experience. Lexington Press. 2018.

- Dan Moller, “Love and Death,” The Journal of Philosophy 104 (2007): 301–16.

- David Rönnegard, “The Party without Me,” Philosophy Now, June-July 2015.

Featured image: Petras Gaglias / CC BY-SA 2.0 (colour edited from original)