How can we mitigate the risks of future pandemics? Jonathan Birch looks at the role of human behaviour in the emergence of new zoonotic diseases.

The gambler’s fallacy

When you’ve just lost big in a game of chance, there’s a strong temptation to think: next time you roll the dice, that won’t happen again. Surely, you’re due some luck! This is known as the gambler’s fallacy. It’s a fallacy because, when you’re looking at a series of independent events (a series of rolls of the dice), it’s not true that losing big means you’re due some good luck. It doesn’t work like that – not when the events are independent.

I think the gambler’s fallacy is almost irresistible when we think about pandemics. We think the fact that a new disease has emerged from the natural world so recently, and caused such a terrible catastrophe, means that we’re due some luck. Surely we must be due a long reprieve before the next one. Surely we will have time to prepare.

Scientists have worried for a very long time about the risk of pandemic influenza. In the UK, we have large documents detailing our “pandemic influenza strategy”. We have groups of advisers who, until the current pandemic, were dedicated to preparing the country for pandemic influenza, such as the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling (SPI-M). It was regarded as the greatest risk to our country.

It’s almost irresistible to think that the fact we are living through a coronavirus pandemic means that risk has subsided, at least for a while. Surely we will get a reprieve. Surely we will not see pandemic influenza this year or next year. In fact, the probability of an influenza pandemic in the near future is virtually unaffected by the fact we’re currently having a pandemic caused by a different respiratory virus, a coronavirus – unless the experience of the coronavirus pandemic leads to a step change in the way we manage the risk of future pandemics.

Risk and proportionality

It’s a wide point of agreement that pandemics are serious risks, and that we should take precautions to try and reduce that risk. The idea that we should take precautions against grave risks, even when we are not sure they will materialise and when the science remains highly uncertain, is an idea often called the precautionary principle.

When we apply the precautionary principle to any risk, the precautions we take should be proportionate to the risk. They should do enough to bring the risk below a certain level: they should make it negligible or as close to negligible as can be reasonably achieved. But they should not be excessive. They shouldn’t go beyond the sort of precautions that can be reasonably required from people while respecting their basic human rights, and they should not create new risks that are as bad as (or worse than) the risk we are guarding against. Moreover, those affected should be compensated where reasonable, and especially when they are not themselves culpable for creating the risk.

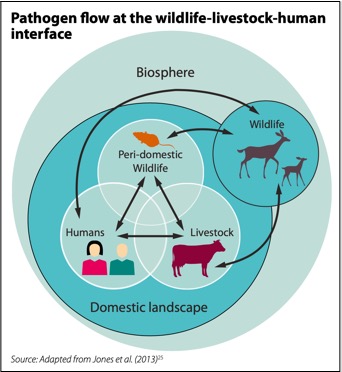

When it comes to pandemics, there needs to be a step change in how we think about proportionality. We have known about the risk for a long time. But the sort of steps we’ve regarded as proportionate to managing that risk have in fact been totally inadequate. The drivers of new zoonotic diseases (diseases moving from animal hosts to humans) are well known, and the most severe drivers are anthropogenic: they are forms of human behaviour (see the UN Environment Programme’s recent report). In particular, surging global demand for meat, plus intensive methods of meat production, substantially increase the risk of new zoonotic diseases emerging. It’s also widely recognised that the wildlife trade substantially increases the risk of new zoonotic disease.

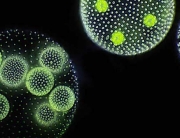

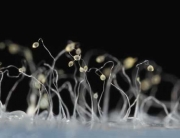

In short, human-animal interaction creates the risk, and the dense packing of genetically similar animals into small spaces exacerbates the risk. Intensive meat production, in which this kind of close-packing is the norm, creates a golden opportunity for a virus to move from a wild population into a large domestic animal population in which it can spread incredibly easily and evolve into a more pathogenic form. In theory, we could prevent this by hermetically sealing off the domestic populations from all wild animals – but this level of biosecurity simply isn’t realistic, especially with birds.

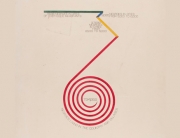

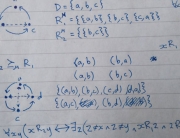

Fig 1.: Image from UN Environment Programme, “Preventing the Next Pandemic”, 2020.

H5N1

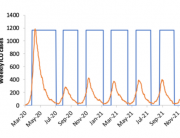

We’ve seen the risk steadily growing in the case of avian influenza – bird flu. H5N1, in particular, has been regarded since the early 2000s as one of the greatest threats to humanity.

H5N1 is a subtype of the influenza A virus. In birds, influenza A has “low pathogenic” strains that do not cause severe disease, and “highly pathogenic” strains associated with severe disease and death. In wild bird populations in which animals are spatially separated, we tend to find “low pathogenic” strains. This is unsurprising: we should expect a highly pathogenic strain that rapidly kills almost all the animals it infects to be outcompeted by less pathogenic strains that keep their hosts alive, because these less pathogenic strains can spread more easily.

By contrast, in populations of tens of thousands of close-packed, genetically similar animals with nowhere to go, a virus is not under a selection pressure to spare its host’s life. It is under a selection pressure to reproduce fast, and transmit fast, regardless of the cost to the host. So it should come as no surprise that highly pathogenic influenza strains have evolved in populations of close-packed domestic animals.

In those rare cases where highly pathogenic H5N1 has infected a human (and this has happened a few hundred times), it is estimated to have an infection fatality rate of somewhere around 60%: around 60 times worse than SARS-CoV-2. The world is spared, for now, because H5N1 cannot transmit between humans – just as, prior to late 2019, SARS-CoV-2 could not spread between humans.

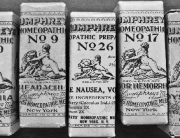

Fig. 2: Photograph by Matthew T Rader, MatthewTRader.com, License CC-BY-SA 4.0

Some proposals

When we have thought in the past about measures that are proportionate to the risk of pandemic influenza, we’ve tended to think small. We thought, for example: could we bring in rules to stop poultry farms being located close to swine farms (pig farms) to reduce the risk of the virus adapting to pigs (our fellow mammals), and then to us? This is a perfectly sensible step, but to my mind, falls short of what is proportionate to a risk that threatens the very future of our civilisation.

We need to be thinking about taking much stronger steps to reduce the risk of a future pandemic. There is a lot more that we can do that is still proportionate and reasonable to require of people, as long as we compensate those who are affected. In particular, we can seek to entirely eliminate the wildlife trade. China has already brought in a ban on the wildlife trade in light of COVID-19, but it only covers uses of animals for food: the trade in wildlife for other purposes continues. I think all countries should be seeking to ban all trade in wildlife and all live-animal markets.

But we need to think even bigger than that. I think we need to be looking to phase out intensive farming of animals for meat, for the sake of our own health. Realistically, this will have to happen gradually, not instantly, but I think it’s clear that it does have to happen. Instead of subsidising operations that are farming animals incredibly intensively and feeding an unsustainable demand for meat, governments need to withdraw those subsidies and instead subsidise plant-based food production.

My last proposal is that governments should incentivise changes in diet. They need to incentivise reductions in meat consumption. There are various other reasons why this is a good idea, but the need to prevent future pandemics is among the strongest reasons. We’ve seen global meat consumption rising and rising over recent decades to a level where the risk of carrying on like this is simply too great. I am suggesting here that governments step in to incentivise people, e.g. through tax incentives, to reduce their meat consumption. This does not have to involve incentivising people to become vegetarian and vegan. Governments could, for example, subsidise initiatives where one day of the week is a meat-free day.

There will be costs to all of these steps. Significant compensation will be appropriate for those affected but not culpable, which may include farmers and legal wildlife traders. But these costs are surely far, far lower than the costs of a future pandemic that has the potential to be many times worse than the one we’ve been experiencing over the past year.

Governments that take the steps I’ve suggested (banning the wildlife trade and live animal markets, moving towards ending the intensive farming of animals, ending subsidies of that industry, incentivising people to eat less meat) will be part of the solution rather than part of the problem. They will be able to say that they are taking meaningful steps to reduce the risk of future viruses jumping from animal hosts to humans. I imagine that would be something of a vote winner. And I think reducing that risk has to be, if not the priority, then a major priority when it comes to shaping the post-COVID world.

Dr Jonathan Birch is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at the LSE and Principal Investigator (PI) on the Foundations of Animal Sentience project. In addition to his interest in animal sentience, cognition and welfare, he also has a longstanding interest in the evolution of altruism and social behaviour.

Further reading

- Akhtar, A. (2021) LSE Festival 2021 | COVID-19 is the consequence of our cruelty to animals. LSE Covid-19 Blog. 5 March 2021.

- Cao, D. (2021) LSE Festival 2021 | To avoid more pandemics, we need to stop eating wild and factory-farmed animals. LSE Covid-19 Blog. 5 March 2021.

- Whitfort, A. (2021) LSE Festival 2021 | China should ban the farming of wild animals now. LSE Covid-19 Blog. 5 March 2021.