The head of the British army, General Sir Patrick Sanders, recently raised concerns over poor recruitment in the military. But as Jonathan Parry from LSE Philosophy and Christina Easton from Warwick University argue, there are deeper, moral concerns with military recruitment. Campaigning at schools, glamourising the work of the army in advertising, and drawing largely from a pool of the socioeconomically disadvantaged young all point to the need for military reform.

Amid ongoing conflicts and concerns that the British Army “continues to shrink before our very eyes”, there has been much recent discussion of how Britain recruits its military. Yet despite conversations about low numbers, diversity-boosting tactics, and conscription, the underlying ethical issues have largely been left untouched. While we are familiar with debating the ethics of how states use their militaries, we tend not to think too much about how states create their armed forces in the first place.

In a recent paper, we argue that the military is not just a job like any other. Alongside the physical and psychological risks, the military is a distinctively morally risky profession. Military personnel face an increased risk of participating in serious moral wrongs. As General Sir Michael Rose puts it, “No other group in society is required either to kill other human beings, or expressly sacrifice themselves for the nation.”

Alongside killing and maiming, participating in war involves destroying homes and livelihoods, forcing people to flee their homes, and many other horrors. When the use of armed force is unjustified, its participants are involved (however blamelessly) in carrying out serious moral wrongs. And even when a military operation is justified, participation still involves the risk of committing war crimes and inflicting disproportionate or unnecessary harm.

Committing (or helping others to commit) unjustified homicide leaves a deep mark on a person’s life – as well as often causing psychological harm. If we care about others, we should care about whether their lives are tarnished by wrongdoing. This involves avoiding exposing others to excessive moral risks and equipping them to deal with the risks that they do face.

When we reflect on our country’s recruitment practices, one question we should ask is how they magnify, concentrate, and distribute moral risk within our community. Of course, all forms of recruitment involve moral risk exposure. But British recruitment practices are particularly objectionable on this front.

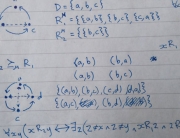

The UK is an international outlier in terms of the youth of its recruits. Young people can join from their sixteenth birthday and may sign up five months earlier. No member of the EU recruits this young, and the UK is the only permanent member of NATO to do so. This has attracted significant criticism, including from the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. Yet 23 per cent of British recruits in the 2021/2022 intake signed up before their 18th birthday (rising to 30 per cent for the army). Alongside the youthfulness of its intake, the UK military focuses its recruitment in areas of socioeconomic deprivation. Those recruited as minors are disproportionately enlisted from these areas.

Young people face an increased level of moral risk because they are more likely to be directed into combat roles. They are also less equipped for moral decision-making. Their brains are still in a process of development that continues until roughly age 25. The pre-frontal cortex – responsible for long-term planning, assessing risk, regulating emotion, and controlling impulsive behaviour – undergoes significant developments for nearly a decade after British children can join the military. This unfinished process of psychological development “leaves some adolescents particularly susceptible to making ill-judged decisions.”

Socioeconomic disadvantage can also aggravate moral risk. First, this demographic is more likely to have experienced childhood adversity, which research indicates increases the likelihood of making decisions based on emotive, rather than rational, reasons. Second, economic deprivation can itself have negative effects on decision-making. There is evidence that poverty imposes a “mental bandwidth tax”, which negatively impacts cognition and self-control. And third, socioeconomic deprivation is associated with educational and informational disadvantage. Three quarters of junior recruits assessed in 2015 had a reading age of 11 or below (with some as low as 5). Educational disadvantage plausibly correlates with a moral-risk disadvantage. Put bluntly: If a recruit cannot read, it will be harder for them to assess their employer’s moral track record.

A concern for moral risk also bears on the broader environment in which recruitment takes place. Potential recruits require relevant information and the capacity for critical deliberation. But the UK falls short in equipping its young people to assess the moral risks of a military career.

One worry concerns the involvement of the military (and related industries) in education. The number of cadet forces has dramatically increased in recent years, now reaching over 500 schools. The armed forces also have a presence in schools through visits, careers fairs and provision of educational resources. These have been criticised for presenting a one-sided picture of the military, emphasising the positives whilst ignoring the physical, psychological, and moral risks involved. One resource (now withdrawn) sent to all schools in 2014 described the “military ethos” as “a golden thread that can be an example of what is best about our nation and helps it improve everything it touches.”

Another concern stems from increasing calls for more patriotism and militarism in British education. For example, in 2012, the UK government launched an initiative to promote a military ethos in schools, fostering the values of “teamwork, discipline and leadership” via military-led projects. Since 2014, schools have been required to promote “British values”, and there has been a political drive for children to be taught to be “proud” of their history.

Whatever benefits these proposals may have, they also exacerbate moral risk. Cultivating pride in one’s country may require downplaying negative aspects of British history, clouding people’s ability to critically evaluate their state’s activities. Similarly, teaching the values of obedience and deference to authority seems inimicable to cultivating independent moral reflection, particularly regarding the military profession.

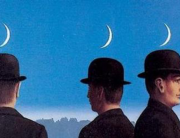

Analogous worries arise from the increasing celebration of, and reverence for, the military across wider society. For example, the emphasis of Remembrance Day has shifted in recent years from solemn reflection on the First World War to honouring all those who serve. Over the same period, Armed Forces Day events (described by one researcher as a “de facto military recruitment fair”) have been rebranded and expanded. These events have faced criticism for emphasising the positives of military service whilst discouraging critical reflection on military policy. Indeed, abstaining from participation in public events (or participating in alternative ways, such as wearing a white poppy) is increasingly cast as ungrateful and unpatriotic. This stifles debate and deliberation about the use of armed force, making it harder to think clearly about the rights and wrongs of military policy and the moral riskiness of the military profession.

Our arguments strengthen existing calls for reforms of military recruitment and service. Most obviously, raising the age of enlistment would be an important step in the right direction. Pollingindicates that the majority of British citizens support raising the recruitment age and researchsuggests that a transition to an all-adult military is economically feasible.

Another avenue of reform would be to require recruitment materials to acknowledge the moral seriousness of the profession and to limit the ways in which the military is permitted to engage with school students.

Military personnel should also be better compensated for the burdens – including the moral burdens – they bear. This could include better pay and housing, a supported pipeline to further education and training (as the US military provides), and improved leaving packages.

But the practical implications of a concern for moral risk are not limited to government policy. The task of creating and maintaining a public culture which avoids excessive moral risk – in which openness, deliberation and dissent are treated as public goods – falls on all of us.

By Jonathan Parry and Christina Easton

Jonathan Parry is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at the LSE.

Christina Easton is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Warwick. She received her PhD in philosophy from the LSE, where she was awarded an LSE-wide teaching award.

Credits

This article has originally been published on the LSE British Politics and Policy Blog of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

I cannot thank you enough for writing this article. I left the Army in 2020 as I began to realise the harm of being inside this system and what I had been part of. I am currently drafting a piece of writing about culture change in the Army and found your article as I was looking for some sources and statistics. It has given me a boost to share my thoughts more publicly. They may not be shared by those still serving but knowing there are people out there who might see what I see is bolstering. Thank you.

Hi Kirsty

Thanks for sharing this and good luck with your article.

Our full article is here and is open access: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/filling-the-ranks-moral-risk-and-the-ethics-of-military-recruitment/AECBBE88736D2AB01470BDB404E537BF

You might also find Robillard and Strawser’s book interesting as they share experiences of soldiers thinking about “moral injury” and share personal stories that you might find something in common with.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Outsourcing-Duty-Exploitation-American-Soldier/dp/0190671459

Also check out Hi Phi Nation’s podcasts on this topic! It’s excellent.

https://hiphination.org/complete-season-one-episodes/episode-two-moral-exploitation-jan-31-2017/