What can corporate actors learn from climate change litigation?

Catherine Higham and Joana Setzer summarise how climate litigation is affecting the private sector, drawing on their recent report, Global Trends in Climate Litigation: 2021 snapshot

In May of this year, climate change litigation made global headlines in the wake of an unprecedented judgment issued by the Hague District Court in the case of Milieudefensie v Shell. The court ordered Shell to enhance the ambition of its greenhouse gas emissions reduction efforts, requiring the company to set – and meet – companywide emissions reduction targets of 45% below 1990 levels by 2030. While this case was the first of its kind, it is also part of a growing global body of climate change litigation, which is playing an increasingly critical role in the domestic implementation and enforcement of the Paris Agreement.

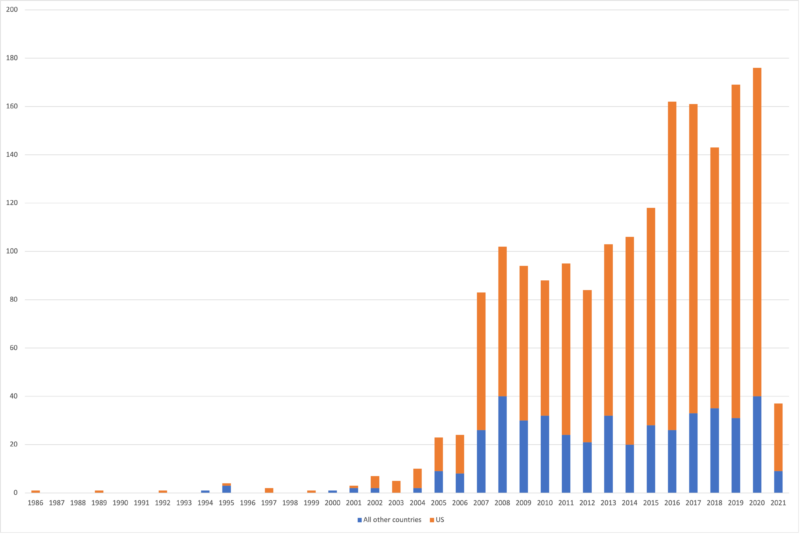

Globally, the cumulative number of climate change-related cases has more than doubled since 2015 (see Figure 1 below). Just over 800 cases were filed between 1986 and 2014, while over 1,000 cases have been brought in the last six years. Among these, cases of ‘strategic’ litigation – cases filed with the express aim of achieving a wider societal goal – have been on the rise. While most litigation continues to be filed against governments, a small but growing group of cases also targets the private sector.

Figure 1. Number of climate litigation cases, 1986 to 31 May 2021

Note: Due to the high volume of litigation in the US, US and non-US data are shown separately.

Source: Authors based on CCLW and Sabin Center data

Direct and indirect litigation against private actors

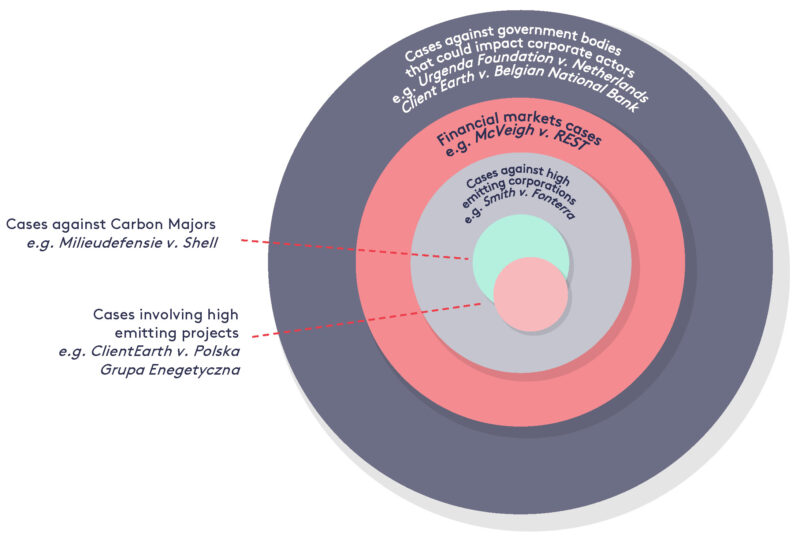

The body of climate change cases is increasingly diverse, with new strategies and arguments being deployed and developed all the time. In this context, it is crucial for corporate actors to understand the range of cases that may impact them. Historically, cases seeking to influence corporate behaviour in the climate context have consisted of cases against the companies with the highest historical emissions (i.e. the Carbon Majors), and cases challenging potential high emitting projects and developments.

Many of these cases focus on the direct and value chain emissions associated with certain activities, often seeking to draw a direct causal link between those emissions and a given set of climate impacts. These cases are pictured in the centre of Figure 2 below. While historically these cases have focused on oil, gas and cement companies, often integrating claims challenging disinformation and greenwashing, we are also now starting to see litigation against other types of companies with a high carbon footprint (such as those in the meat and dairy industry), pictured in the next ring out. However, these ‘direct cases’” are far from the only cases that may seek to influence corporate action.

Finance in focus

We have identified two other key types of litigation that could have major – if indirect – impacts for business practices. Firstly, we see a growing number of cases involving actors from the financial services industry. Such cases ultimately seek to influence emissions trends by increasing the cost of capital for high emissions activities. Early examples of this type of litigation focused primarily on the disclosure of climate-change related risks and their relevance to investment decisions, often drawing on the recommendations and guidance produced by the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). This line of cases involves claims by shareholder activists against specific companies, as well as cases against asset managers such as pension funds.

However, as Colombo has argued, recent cases such as McVeigh v. Retail Employees Superannuation Trust (REST) appear to mark a move beyond cases focused on disclosure to cases focused on due diligence. In McVeigh a pension fund subscriber argued that in failing to adequately manage climate risk, the trustees of the fund had neglected to carry out the duties of care, skill and diligence owed to the Trust’s beneficiaries. The case ultimately settled as a result of REST’s decision to align its investment portfolio with the goals of the Paris Agreement and adopt a target of net-zero emissions by 2050, but preliminary rulings from the court, coupled with the Trust’s subsequent actions, clearly demonstrate the ‘salience’ of the arguments put forward.

The impact of ‘climate commitments cases’” against governments

The other group of cases that may have far-reaching impacts for business involves legal challenges to governments, which seek to challenge either a lack of ambition or a lack of implementation for climate goals (pictured in the outer ring of Figure 2). In our report we identify over 100 such cases, which often centre on climate commitments or targets, building on the emerging consensus around global temperature limits represented by the Paris Agreement and reinforced by the publication in 2018 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of the Special Report on 1.5 Degrees, as well as the growing popularity of the concept of ‘net-zero’.

More than half of this group of cases (37) build on the approach taken in the landmark case of Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands, which was the first piece of litigation to successfully challenge the adequacy of a national government’s overall approach to reducing emissions. Whether successful or not, such cases may often result in increased government ambition, and correspondingly in increased regulation focused on private sector emissions.

Figure 2. Direct and indirect cases affecting the private sector

Source: Authors

Looking forward: the challenge of net-zero

The Shell case discussed above represents one of the first clear judicial determinations that the 1.5°C temperature limit, referred to in Article 2.1(a) of the Paris Agreement, and generally understood as requiring the global community to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century, should be used to inform legal standards of conduct in the absence of explicit legislation. Crucially, in confirming Shell’s legal responsibility to align its operations with global efforts to meet this goal, the Court emphasised the need for Shell to reduce both its direct and value chain emissions. This emphasis on the need for companies to have concrete and credible climate policies encompassing both the net-zero goal and value chain emissions is likely to be a key element of how climate law and litigation affect the private sector in the short term.

A similar case is already ongoing in France, and since the publication of our report new cases modelled on Shell have now been threatened against auto manufacturers and the oil and gas industry in Germany. Meanwhile, Australia has also seen potentially precedent-setting litigation on net-zero filed in recent months: a case against gas company Santos filed by the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility is challenging the company’s claims to have a clear and credible plan to reach net-zero on the grounds that it constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct.

Conclusions

Climate change litigation continues to grow and diversify, spreading to increasing numbers of jurisdictions and areas of law. This growth and diversity reflect the increasing urgency with which the climate crisis is viewed by citizens around the world and the growing understanding of the role all actors – including businesses and investors – will need to play in the transition to a net-zero global economy.

This commentary has also been published by the LSE Business Review.