Have you ever wondered why doing ‘what you ought’ has to be so hard? LSE Professor Lea Ypi from the Department of Government offered a promising answer during her talk ‘How capitalism undermines freedom’ organised by LSE’s Cohesive Capitalism programme. According to Professor Ypi, it is capitalism itself that shackles us by imposing ‘structural’ constraints on our freedom. In our new LSE Philosophy blog post, PhD student Vita Kudryavtseva examines this proposal more closely.

Structural constraints

Professor Ypi works with the negative conception of social freedom, meaning that freedom is understood as the absence of actual (or highly likely) constraints on the agent’s actions. Ypi puts forth the idea that capitalism engenders a special kind of constraint on the agent’s freedom, the so-called ‘structural constraint’. Say, if the terms of your employment agreement preclude you from sharing with the world your groundbreaking discovery that can save millions of lives, you are unfree to act as you ought. On Ypi’s account, it is irrelevant whether anyone bears moral responsibility for imposing the constraint. Similarly, it matters not whether the constraint is arbitrary or well-justified. Anytime you are prevented from “doing the right thing” by a social or legal norm, this norm counts as a structural constraint on your freedom. Full stop.

To be clear, Ypi’s primary concern is not whether a socio-economic system prevents us from getting our way once in a while. Rather, she is interested in how structural constraints interfere with our moral choices. She argues that they do interfere in a very specific way: an agent knows the “right thing” to do and yet is prevented from doing it. Thus, the structure messes with an agent’s ability to lead a moral life, yet it does not completely corrupt the agent’s moral compass, forcing her to lose sight of the “right thing” entirely.

Central to Ypi’s thesis is the idea that these constraints undermine the freedom of all agents, regardless of their position on a social ladder. The powerful and the powerless, the oppressors and the oppressed – everyone feels the brunt of structural constraints, albeit to a varying degree. Ypi motivates this point with a story of a chance encounter with an oligarch at a dinner party. Here, I take a few liberties to reconstruct the story for our purposes.

The tale of a remorseful oligarch

There was once an oligarch from a small but feisty country. He was noble at heart and of reflective disposition. The oligarch felt deeply for the plight of his workers and wished for nothing more than to increase their pay. In fact, he considered this to be absolutely the ‘right thing’ for him to do! However, when a dinner companion asked why the oligarch wouldn’t just go ahead and raise the wages, his eyes grew moist and with a soft chuckle he said: “My dear friend, my hands are tied – the market is the Beast! So, if I were to pay my workers more, my business will soon decease…” (He was also a bit of a rhymer). The moral of the story is clear enough: even oligarchs are not free from the structural constraints of the very structure that elevated them. Before we assent to the idea of the oligarch’s structural unfreedom, let us probe this issue a bit further. In what follows, I build upon Ypi’s example for further analysis.

Oligarch’s unfreedom examined

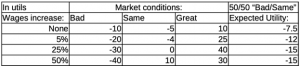

Now, imagine how this conversation could go forth if the dinner companion, just like us, finds the oligarch’s explanation a bit incredulous. For instance, she may point out that “paying workers more” can be accomplished in a number of different ways. It is quite a bold claim to say that every possible action to this end is foreclosed to the oligarch. “How do you know that there is nothing you can do?” she presses. “Oh…” – the oligarch responds – “Of course, I’ve got my guys to run the numbers. Look, here’s the analysis:

The truth be told,” – he continues- “I think the “great” market conditions ain’t happening. I see things getting worse or staying the same at best… Even with a healthy helping of moral goodness offsetting some of the financial losses, I’d be a fool to raise wages right now.”

“Wait a minute, but all this really ‘proves’” – the guest counters – “is that it is not the best choice for you right now – a very contingent fact. When I am waiting for a bus, I am not ‘unfree’ to ride a bus just because it hasn’t come yet. Assuming buses run at all, I am free to ride one once it comes. Markets are just like buses. Assuming they ‘run’ at all, it is in their nature that profit margins change, good times come and go, and when some products fail, the others take their place.”

Irritated, the oligarch interjects – “Fine, then, what would you have me do? There is nothing I can think of!”

Freeing the Oligarch

Well, here’s a couple of things she could have him do:

(i) Adjust time horizon

Assuming the oligarch really cares about ‘paying his workers more’, and considers this important, he has a good reason to construe his decision situation differently. Caring about something is a persistent attitude. (Frankfurt, 1982) The cares give rise to desires such as to see what we care about thriving or to promote its happiness. (Shoemaker, 2003) In this particular case, caring about ‘paying workers more’ straightforwardly occasions the desire to increase workers’ pay. Importantly, because of the persistent nature of the care, the Oligarch can anticipate that these desires will pop up time and again. Therefore, the Oligarch should represent the decision situation not as a one-time, isolated choice – (a) “How can I raise workers’ wages right now?” – but as a longer time horizon decision – (b) “How can I ensure fair compensation over time?”. Just like when you know you care about a particular theatre and want to see their multiple performances every season – ‘Consider becoming a member!’ – rather than hustling for a ticket every single time.

(ii) Adjust possible actions

There is another striking inadequacy in the Oligarch’s representation of his decision situation – his overreaching, powerful agency is nowhere to be found! His story about being at the mercy of market forces is fit for a small coffee shop owner on a busy street, but not for an oligarch, the captain of the industry, the wielder of political power par excellence. One way to understand the instrumental value of agency is by looking at the set of actions that a decision-maker could take. For example, in an organisational structure, the position of a CEO corresponds to one set of possible acts and that of a line manager to a different, presumably narrower set. Similarly, an oligarch can do a whole lot more than simply “increase wages X%” as a way of fulfilling his desire “to pay his workers more”.

Combining (i) and (ii), the Oligarch can develop a more astute representation of his problem. He could, for instance, consider such actions as changing the ownership structure of his business to increase the workers’ share, providing free training and education, enacting minimum wage laws, and so on. While it is hard to tell what kinds of actions are really within his reach, what should be clear is that these examples are more becoming of his stature and the importance he places on economic equity.

Coda

Where does this discussion leave us? Ypi’s account of unfreedom asserts that structural constraints preclude everyone, even the powerful actors, from “doing the right thing”. To maintain that every possible action for the sake of a moral end is indeed foreclosed to an agent, we have to have some sense of what these actions are, what their consequences are, etc. – in other words, we need a ‘decision representation’.

Importantly, this problem is specific to Ypi’s account of ‘structural constraints’ as it does not arise in straightforward cases of agential domination. For instance, in the often-cited example of slavery, we don’t need to know what actions a slave can perform because a master can arbitrarily block any of them. Hence, a slave is dominated by a master. Domination by ‘structure’, on the other hand, does not operate in the same way, as social and legal norms impede only some but not all of the agent’s actions.

What I hope to have shown in my limited critique of Ypi’s proposal is that in the oligarch’s case, the simplistic decision representation is inadequate and thus this case does not suffice as a justification for the thesis. Hence, we are still left wondering whether capitalism’s structural constraints really stifle our moral selves.

By Vita Kudryavtseva

Vita Kudryavtseva is a PhD student at the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Her research ares are decision theory (uncertainty), philosophy of probability, philosophy of imagination, and social ontology.

Notes

Frankfurt, Harry (1982). “The Importance of What We Care About”. In: Synthese 53.2, pp. 257–272

Shoemaker, David W. (2003). “Caring, Identification, and Agency”. In: Ethics 114.1, pp. 88–118

Connect with us

Facebook

Twitter

Youtube

Flickr