How climate laws create impact

Alina Averchenkova and Tiffanie Chan summarise their recent work on the impact of climate change framework laws that has drawn on case studies from the UK, Germany, Ireland and New Zealand in particular.

Many countries around the world have introduced climate laws, which establish the institutions to govern national climate change policy and direct action on climate mitigation, adaptation, disaster risk management and loss and damage. The term ‘climate framework laws’ refers to an important subset of climate legislation. These laws are passed by legislative branches of government and set out the strategic direction for travel for national climate change policy. They often contain national mid- or long-term emissions reduction targets or pathways, are multi-sectoral in scope and involve mechanisms for transparency and accountability.

As of October 2025, the Climate Change Laws of the World database, maintained by the Grantham Research Institute, records over 1,500 climate laws, including 75 climate framework laws across 69 countries.

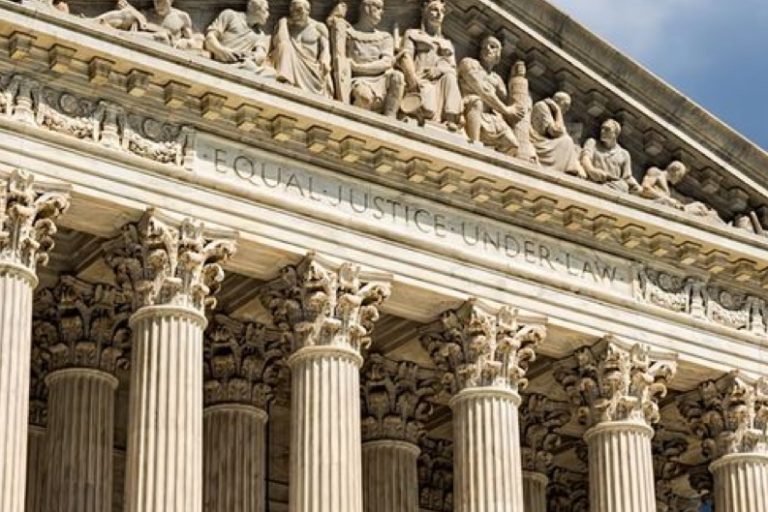

But do climate change laws create impact and in what ways? Research on the impacts of climate framework laws across the UK, Germany, Ireland, and New Zealand finds six key provisions through which these laws exert impact: (a) setting of targets and carbon budgets; (b) requirements to report, assess and review progress; (c) creation of economy-wide and sectoral plans and policies; (d) obligations to mainstream climate change considerations in public decision-making; (e) access to independent expert advice; and (f) processes for public participation.

These provisions can help drive a whole-of-government response, stronger accountability and enabling conditions for just transitions – see Figure 1.

Figure 1. How climate laws create impact

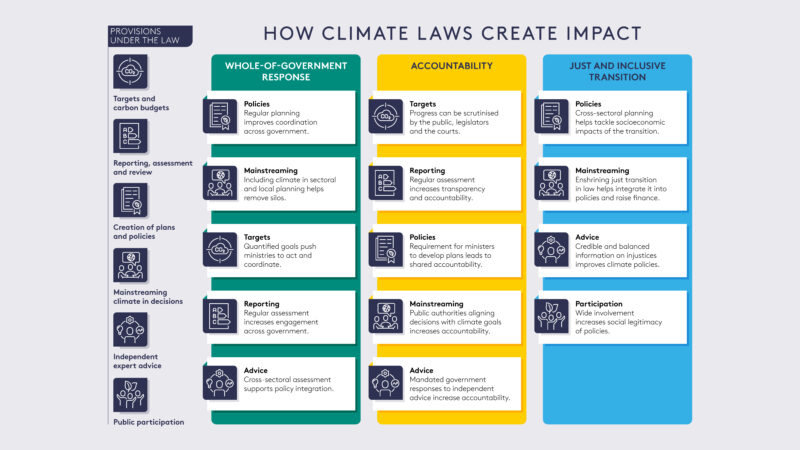

Daily decisions by public authorities can have positive or negative impacts on climate change (see Figure 2). They need a clear mandate and resources to understand the impacts of their decisions for climate outcomes. Climate laws can require public officials to align their decisions with climate goals, and the plans and strategies developed to meet them. The more specific these mandates can be made, the more likely they are to result in good decisions and synergies across government. A 2024 study of Ireland’s regulatory framework found that strong legally binding language requiring decisions by public bodies to be ‘consistent with’ the national climate action plan was associated with impacts on strengthening accountability and engagement from key sectors.

Figure 2. How can laws integrate climate change in decisions by public bodies?

The creation and strengthening of independent expert advisory bodies on climate change through climate framework laws were among the major impacts mentioned in all four countries studied (see Figure 3). Through provision of depoliticised and credible information, and assessment of progress and advice, they help improve the quality of the political debate, policymaking and accountability. However, the relative impacts of these bodies vary. This variation is influenced by the scope and clarity of their mandates, resourcing and capacity – in particular, the strength of the statutory requirements on government to consider and respond to their advice.

Research by the Grantham Research Institute assessing the first 10 years of the UK Climate Change Committee’s (CCC) operation provided empirical evidence of its role as a knowledge broker that offers trusted information to Parliamentarians across the political spectrum. We found that between December 2008 and May 2018 the CCC and its Adaptation Committee (previously the Adaptation Sub-Committee) were referenced in more than 850 Parliamentary interventions, with most political parties mentioning the CCC at least once.

In Ireland and New Zealand, expert advisory bodies have prompted increased engagement with challenging and novel policy issues. Due to being independent, they can approach debates from a different angle than governmental departments. For example, in both countries, they were instrumental in facilitating discussion on emissions in agricultural and forestry sectors. In Ireland, the Climate Change Advisory Council’s annual analysis of progress on climate action was described by interviewees as “a defence against even further slippage”. Its evidence was key to justifying an increase in the national carbon tax and an end to government subsidies for peat and coal burning.

Figure 3. Expert advisory bodies

Over 30 climate framework laws contain legally-binding emissions reduction targets. Enshrining targets, or target-setting processes, in law can strengthen oversight and political accountability, increased coordination between, and engagement from, ministries, as well as send signals to subnational and non-state actors (see Figure 4). Regular assessments of progress against targets increases the frequency of political debate on climate action and focuses scrutiny on specific policies to reach targets. Clear sectoral targets can help increase engagement and pressure on ministries not traditionally associated with climate change-related mandates. In New Zealand, although the climate framework law placed the primary responsibilities for action on the Minister for Climate Change, many New Zealand interviewees felt that the improvement in coordination flowed from the requirement to create an Emissions Reduction Plan, which must include sectoral policies and plans for achieving the targets.

Figure 4. How do targets deliver impact?

An ambitious climate law, particularly one adopted with cross-political party support, creates expectations, making it more politically difficult to reverse. However, a climate law alone cannot prevent backsliding from climate goals, but it can help create the foundations to provide sustained political pressure. Reliance on the legislation by the private sector and the threat of litigation by civil society groups are among the most important factors that may work against backsliding. By the end of 2024, 128 cases had been filed against governments globally – challenging the ambition or implementation of national or subnational climate targets and policies. Many of these challenges challenge the implementation of climate framework laws, with just over 40% of these decided ‘government framework’ cases successful before the courts.

It can be difficult to attribute impacts or effects on the real economy directly to a climate framework law, as the law operates alongside a vast array of sectoral (e.g. energy) laws and climate policies. However, there is increasing evidence that these laws are an effective tool for addressing the central governance challenges around weak cross-sectoral coordination, political short-termism and piecemeal approaches in policy planning, and weak accountability for implementation.