Why the government’s plans to reach net zero don’t add up

The UK Government has published further details about its strategy for decarbonising the economy. But, as Esin Serin and Bob Ward explain, doubts remain about whether it is sufficient to reach the statutory target of net zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050.

Boris Johnson’s Government was humiliated in July 2022 by a High Court ruling that it had not fully complied with the terms of the 2008 Climate Change Act when it published its Net Zero Strategy in September 2021 ahead of the COP26 United Nations climate change summit in Glasgow.

The Strategy claimed that it “sets out clear policies and proposals for keeping us on track for our coming carbon budgets, our ambitious Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), and then sets out our vision for a decarbonised economy in 2050”.

In particular it stated that it “set out a delivery pathway showing indicative emissions reductions across sectors to meet our targets up to the sixth carbon budget (2033-2037)”.

Coming up short

The Sixth Carbon Budget requires the UK’s annual emissions of greenhouse gases to total no more than 965 million tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent for the five-year period between 2033 and 2037. This translates into a 78% reduction in average annual emissions compared with the 1990 baseline year.

However, the Government had already been warned that the Net Zero Strategy was insufficient when the statutory Climate Change Committee published its annual progress report in June 2022. It stated: “The UK Government now has a solid Net Zero strategy in place, but important policy gaps remain”.

This was confirmed by the ruling the following month on the three legal challenges brought by Friends of the Earth, ClientEarth, the Good Law Project and Jo Wheatley, which concluded that the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy had not provided sufficient details about how the Government would reduce emissions in line with the Climate Change Act and the statutory carbon budgets.

A promising new strategy?

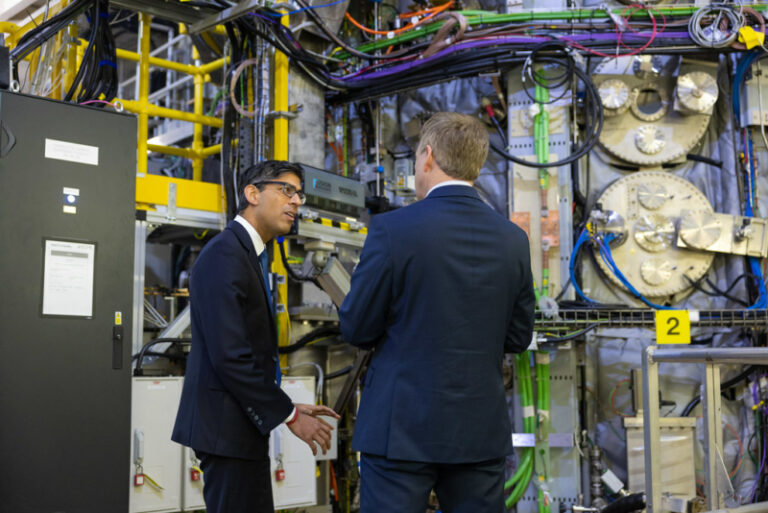

Rishi Sunak’s government published Powering Up Britain along with several other documents on 30 March 2023, hoping to prevent a further adverse ruling from the High Court.

The main document states that it “sets out how the government will enhance our country’s energy security, seize the economic opportunities of the transition, and deliver on our net zero commitments”. It outlines many existing policies as well as a few new ones.

But the accompanying Carbon Budget Delivery Plan acknowledges that even with “new and early stage proposals and policies”, the UK would still exceed its statutory Sixth Carbon Budget by 199 million tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent.

However, it asserts: “We are confident that Carbon Budget 6 can be met through a combination of the quantified and unquantified policies identified”.

Some of the key “new” policies that are included in Powering Up Britain had been announced or leaked in the previous days and weeks.

Perhaps the most eye-catching announcement was an investment of up to £20 billion in the early deployment of carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS), which was included in the Spring Budget presented by the Chancellor of the Exchequer on 15 March 2023.

It stated: “This unprecedented level of funding for the sector will unlock private investment and job creation across the UK, particularly on the East Coast and in the North West of England and North Wales. It will also kick-start the delivery of subsequent phases of this new sustainable industry in the UK, taking advantage of the country’s natural comparative advantage in CCUS.”

In his speech, the Chancellor said that this investment “will support up to 50,000 jobs, attract private sector investment and help capture 20–30 million tonnes of CO2 per year by 2030”. However, it is unclear over what period the £20 billion will be provided, with some media reports suggesting it would be 20 years, and the sum did not appear in any of the departmental budgets laid out by His Majesty’s Treasury.

Powering Up Britain notably lacked any significant new policies to substantially accelerate and increase the deployment of renewable power or energy efficiency measures. The plans also failed to respond to a letter from nearly 700 members of the research community to Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, calling on him to use the new net zero strategy to rule out any new UK onshore or offshore development of oil and gas.

Financing flaws

Perhaps the biggest weakness of the Government’s new strategy is the absence of an ambitious and explicit investment strategy to mobilise public and private finance in support of the transition to a net zero economy, notwithstanding the 2023 Green Finance Strategy that was published alongside Powering Up Britain.

The Independent Review of Net Zero led by Chris Skidmore MP, the former Energy Minister, placed an overarching investment strategy at the top of its list of 129 recommendations when it was published in January 2023. It stated: “Government should publish an overarching financing strategy covering how existing and future government spending, policies, and regulation will scale up private finance to deliver the UK’s net zero-enabled growth and energy security ambitions”.

The review had been commissioned in September 2022 by Jacob Rees-Mogg, the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in Liz Truss’s Government, who was seeking to appease critics of net zero policies.

But the review concluded: “Net zero is the growth opportunity of the 21st century”. It warned: “We must move quickly. We have heard from businesses that economic opportunities are being missed today because of weaknesses in the UK’s investment environment – whether that be skills shortages or inconsistent policy commitment. Moving quickly must include spending money.”

From leader to laggard?

The Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, was challenged when he appeared before the House of Commons Treasury Select Committee on 29 March 2023 about the risks of the UK failing to respond adequately to the massive investments in net zero infrastructure and technologies by the United States through the Inflation Reduction Act and by the European Union through its Green Deal.

He promised the Committee that the government would respond more fully to these developments in the Autumn Statement later this year. He acknowledged the need to “mitigate those risks”, but argued: “That does not necessarily mean matching subsidy for subsidy, but it means making sure that the overall package that means people choose to invest in the UK remains attractive.”

It is not clear if the new net zero strategy will satisfy campaign groups and the High Court, or whether it will be sufficient to maintain the UK’s international leadership on climate change.

This commentary was first published by the LSE British Politics and Policy Blog on 21 April 2023.