Why the fate of the Amazon is a growing issue for investors in sovereign bonds

Investors have recently added their voices to the chorus of concern about the fires in the Amazon rainforest. The 80,000 fires in the Brazilian Amazon this year have coincided with the climate crisis and the accelerating loss of nature rising towards the top of the financial agenda. In response, 246 investors with US$17.5 trillion in assets have signed a global statement that calls on the companies they own to eliminate deforestation from their supply chains.

Investors are demanding that companies disclose and implement zero deforestation policies with quantifiable and time-bound commitments, establish transparent monitoring and verification systems for supplier compliance and report annually on deforestation risk exposure and management.

The investor statement is another sign of the growing willingness of investors to use their voice to press for improved environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices. It sends a market signal that reinforces the actions by companies such as VF Corp (parent to brands including Vans, Timberland and North Face) and H&M, which have announced they will no longer purchase leather from Brazil. On the financial sector side, KLP – Norway’s largest pension fund – has also announced the possibility of divesting from commodities traders operating in Brazil that are contributing to deforestation.

Importantly, the investor statement is clear that it is supporting efforts from Brazil’s own private sector to promote sustainable practices in the Amazon. The Brazilian Business Council for Sustainable Development (CEBDS) has issued a statement defending deforestation control to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and the Brazilian Coalition on Climate, Forests and Agriculture called in September 2019 for a halt on deforestation on public lands.

Linking ESG factors to sovereign debt risk

To date, investors’ focus has been mostly on the links between the stocks and shares they own and deforestation. But there are examples of investors accelerating efforts to understand how sustainability factors impinge on the $66trn market for the sovereign debt issued by governments. For instance, Nordea Asset Management has quarantined its purchases of Brazilian sovereign debt.

In September 2019, the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) issued the first guide to how ESG factors can be integrated into sovereign debt risk, building on research and analysis by signatories to the PRI. Earlier this year, for example, BlueBay Asset Management and Verisk Maplecroft published research that highlighted how markets are not yet pricing environmental or climate change risks into the prices of sovereign bonds. In fact, markets seem to incentivise economic expansion at the expense of natural capital in those countries with higher natural resource stock, which could mean such markets are being set up for an abrupt repricing in relation to climate change. The PRI guide recommends investors undertake in-house country-level research and develop materiality frameworks that can highlight red flags like this and define the need and process for engagement.

Credit rating agencies are also working on linking climate risks to the vulnerability of sovereign bonds, with actions being taken by each of the ‘big three’. For example, as early as 2014, S&P Global Ratings, defined climate change as a megatrend for sovereign credit risk, affecting countries’ creditworthiness through diverse channels and with poorer and lower rated sovereigns to be affected the hardest. Moody’s Investors Service has developed a heat map identifying that small, agriculture-reliant sovereign issuers are most susceptible to climate change and has highlighted that ESG factors can affect sovereign credit ratings in multiple ways. And Fitch Ratings has published relevance scores for public finance and global infrastructure ratings.

However, environmental factors still feature low in credit rating opinions themselves – and these efforts have not yet extended to deforestation.

Why investors in sovereign bonds should act on deforestation

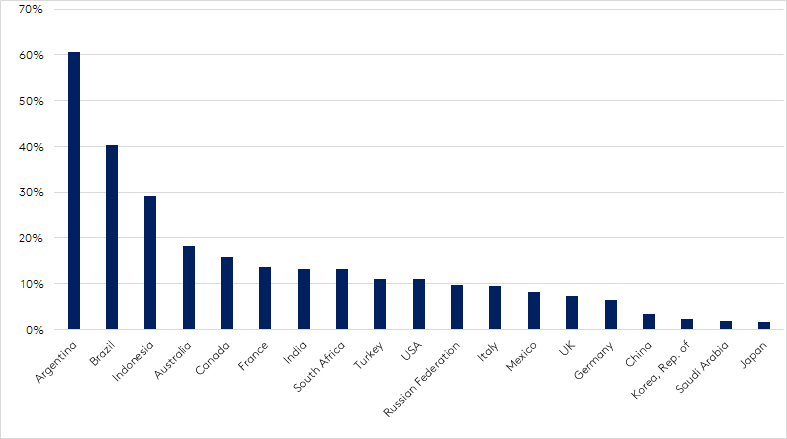

Investors should start by recognising the potential connections between agri-business, natural capital loss, such as deforestation and reduction in water availability, and the value of sovereign bonds. For example, in terms of agricultural trade Argentina and Brazil are the two G20 nations most dependent on nature-based exports, many of which have historically been linked to deforestation (see Figure 1). As sustainability expectations rise in capital markets, it will be important for investors to trace the chain of impact between these keystone sectors in the economy and the future health of sovereign bonds.

There is a question mark over the legality of the deforestation that preceded the fires this year and investors should monitor this situation. Brazil has a relatively strong regulation designed to curb the loss of natural capital, but its monitoring and enforcement is insufficient. Further, analysis suggests that deforestation has increased significantly under President Bolsonaro’s government. Rule of law and institutional effectiveness should be criteria for both credit rating scores and investor frameworks for evaluating sovereign bonds.

Avoiding catastrophic damage to the global economy is another reason for action. As a G20 nation, Brazil is a focus of investor efforts to put in place the policies that are needed to deliver the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change. Although investors are often nervous about getting involved in what could be seen as political debates, dialogue between investors and issuers of sovereign bonds is happening and, increasingly, is including expectations on sustainability performance.

A new set of forecasts, commissioned by the PRI and known as the Inevitable Policy Response (IPR), are helping inform action. They include a prediction that by 2030 deforestation will be largely eliminated as a result of national and bilateral payments to support nature-based solutions to the climate crisis. Carbon dioxide removal will be essential to achieve climate targets and afforestation, reforestation, restoration of degraded land, soil carbon sequestration and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage are the only options with understood sequestration potential and that could deployed at scale. The question for investors is whether Brazil’s sovereign bond ratings are aligned with the shock that these disruptive climate measures will bring.

Three steps sovereign investors can take

- In-depth evaluation of the health of sovereign bonds from countries impacted by deforestation.

This could involve an assessment of the quality of environmental governance as well as more quantitative analysis of how deforestation could impinge on a country’s credit risk over the next decade – the period covered by the IPR forecast. Investors could develop their assessments in-house or collaborate with other organisations.

- Communicate the results of this analysis to the issuers of sovereign bonds.

Collaborative efforts would prove the most effective here; the Emerging Markets Investors Alliance (EMIA) is taking this approach. Investors might need to assess the need for, shape of and vehicles for engagement with sovereign debt issuers. Depending on the answers they receive, investors could alter their asset allocation.

- Signal willingness to invest in sovereign bonds dedicated to regenerating a country’s natural capital.

Globally, the green bond market has been expanding strongly and by July 2019 12 countries had issued green sovereign bonds. Brazil has recently called on rich country governments to pay billions to protect the Amazon. A complementary approach would be for Brazil to issue a green sovereign bond, with the proceeds ring-fenced to curb illegal fires, halt deforestation and support sustainable development in the Amazon. Chile recently issued its own sovereign green bond and earned the lowest rate of interest in its history. For Brazil, a sovereign green bond focused on ending deforestation would mobilise capital markets behind positive action and ensure that the Brazilian government would have ‘skin in the game’. Investors need to show they would be willing to invest.

The Grantham Research Institute and Planet Tracker are collaborating on in-depth research examining the links between natural capital and sovereign bonds, focusing initially on Argentina and Brazil. They will publish their results in early 2020.

Alexandra Pinzón is a Policy Fellow at the Grantham Research Institute; Matthew McLuckie is Director of Research at Planet Tracker; Nick Robins is Professor in Practice – Sustainable Finance at the Grantham Research Institute; Gabriel Thoumi is Director of Financial Markets at Planet Tracker.

This commentary is based on a briefing that has been published by Planet Tracker with support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through the Finance Hub which was created to advance sustainable finance.