How many green jobs are there in the US?

According to a new report from the International Renewable Energy Agency there are 10.3 million renewable energy jobs globally – a 5.3 % increase since 2017. The latest report on the makeup of the US energy sector work force also revealed that renewable energy employment is growing. During 2016, the US solar workforce increased by 25% and the number of employees in the US wind energy industry increased by 32 %.

Whilst these reports indicate that the number of employees in green jobs is growing they look at only at the energy and electricity-generation sectors. In the US the electricity-generation sector is relatively small at around 5% of the total workforce.

In our latest research we used data on the US job market to estimate how many green jobs there are in the rest of the US workforce and, for those jobs which are not green, how the transition to a low-carbon economy could affect them.

1 in 10 US workers already carry out green tasks in their jobs

The US Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) estimate that in 2011 2.6% of the US workforce were employed in the production of green goods and services. These jobs reduce fossil fuel usage, decrease pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, involve recycling materials, increasing energy efficiency or the development of renewable energy sources.

However, in our recent paper in the journal Energy Economics, we estimated that the actual number of people in jobs already supporting the green economy could be much higher.

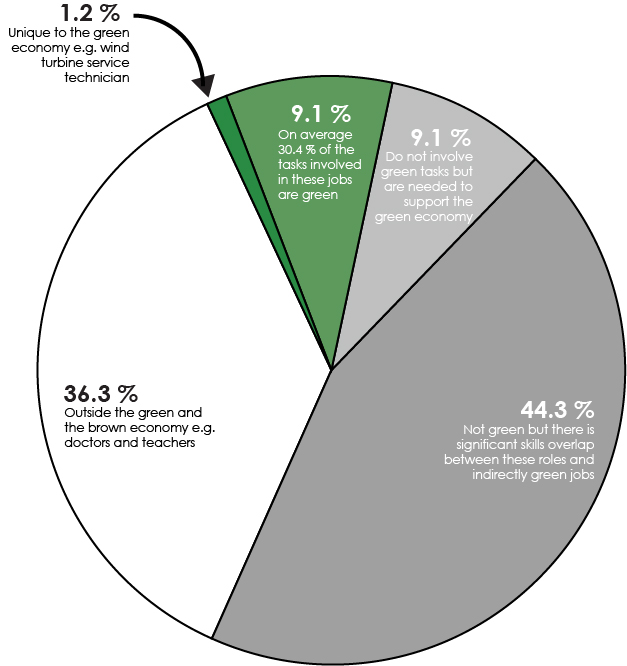

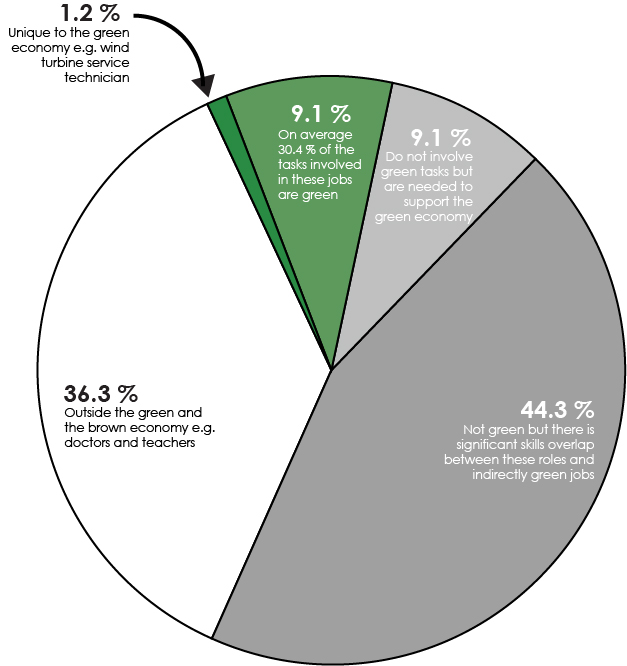

Using data from BLS from 2014 and from the US department of Labour’s Occupational Network Database (O*NET) we found that there is a spectrum of green jobs. Most estimates of green jobs only include occupations which are unique to the green economy, for example wind turbine service technicians or solar photovoltaic installers. When we looked at the O*NET data we found that there are many occupations which involve some green tasks but are sometimes excluded from estimates of green jobs.

We found in our analysis that 1.2% of US jobs are unique to the green economy. On average, 59.4% of the tasks involved in these jobs are ‘green tasks’ as defined by data we used from the O*NET dataset, which looks at the types of tasks involved in 858 (out of 974) US occupations and how often the tasks are carried out.

An additional 9.1% of the workforce are doing green tasks in their jobs but less often, for example workers who are urban and regional planners or refuse and recyclable material collectors. On average, 30.4% of the tasks carried out in these jobs are green.

When we included all jobs in which workers are currently undertaking at least one green task per year we estimate that 10.3% of current US jobs are ‘green’.

What proportion of the US workforce is green?

Another 9% of workers could already support the green economy

Our analysis highlights that a further 9.1% of the US workforce are in jobs which will be necessary to support the green economy but which do not directly support green tasks. We call these ‘indirectly green jobs’.

For example, financial analysts might forecast or analyse financial costs of climate change, identify environmentally-sound financial investments, and recommend environmentally-related financial products. These jobs do the behind-the-scenes work that contributes to green economic activity.

It is not easy to say how many of the workers in this category are currently supporting the green economy. However, we can say that these workers should be able to transition to working in jobs which support the green economy with little retraining since they will not need any new skills.

How much retraining will the rest of the workforce need to work in the green economy?

The retraining needed for many workers to work in the green economy could be much more limited than expected.

Our analysis showed that another 44.3% of US workers already have the transferable skills needed to contribute to the green economy. With limited retraining they could take up indirectly green work. For instance, retail workers could transition to work in retail for green products (for example solar panels, or sustainably produced goods) and coal workers could transition to jobs in the solar photovoltaic industry due to overlapping skills.

This type of job movement could fuel a rapid increase in the workforce to support the green economy. In the longer term the ‘greening’ of the labour market will require transitions to directly green jobs which are unique to the green economy (e.g. environmental engineer, recycling operator) which represent a wider skills gap and may require specific training.

And of course there are jobs which will not be effected by the low-carbon transition. 36.3 % of US jobs, for example doctors and teachers, will remain the same after the low-carbon transition.

The ‘greening’ of the US labour market will be less disruptive than the IT revolution

The labour market will change as the US economy becomes greener, and the changes could be broad. In the late 1980s the labour market underwent another significant shift during the IT revolution. Studies have shown that information and communication technologies accounted for up to a quarter of the growth in demand for highly educated workers during the period 1980 and 2004 across eleven developed countries. Our analysis indicates that while some retraining is needed, the greening of the workforce in the US will not be as disruptive as the changes under the IT revolution.

There is lots of potential for growth in the green workforce if career moves are strategically managed. Some ideas might be to encourage people planning a job change to apply for green jobs. Employers could help workers get experience of green work environments through job rotation or collaboration with green workers. This could help them learn to use their existing skills in a new way.

Karlygash Kuralbayeva is a Fellow in Environmental Economics at the Department of Geography and Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science and an Associate at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. The views expressed in this commentary are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Grantham Research Institute.