Harnessing the UK’s strengths for green growth

Esin Serin and Pia Andres set out evidence on the UK’s sectoral and technological strengths to assist policymakers as they consider how to allocate support across the economy in a way that maximises green growth opportunities.

Green industrial policies have been on the rise in recent years. Countries are using such policies to develop domestic capabilities to tap into growing global markets for green technologies and services as the world tries to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. With the UK progressing its own green industrial policy agenda, policymakers need to understand where best to allocate support.

Importance of a targeted approach in the UK context

While not a ‘magic cure’, evidence suggests supporting green sectors and technologies can be growth-inducing for an economy. For example, the International Energy Agency has found that 10% of global GDP growth in 2023 was attributable to the manufacturing, deployment and sales of clean energy technologies. Policymakers looking to implement industrial policies to drive green growth need to appreciate their local context and act with a hard-headed understanding of the sort of economy they are dealing with. For the UK this means a tight fiscal position, a productive but small manufacturing base, and a relatively small domestic market. These factors imply the UK would be best served by a targeted approach to allocating support that is informed by a comprehensive understanding of the technologies and sectors in which the country has existing or latent strengths.

The Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) and the Grantham Research Institute at LSE have been working together for several years[i] to shed light on the UK’s strengths relevant for capturing green growth opportunities by analysing data on trade and innovation activity. In our current work[ii] we are pulling together evidence on how a set of selected technologies stand to contribute to national objectives such as reducing emissions, enhancing energy security, capturing growth opportunities through firms serving growing domestic and global demand, creating jobs across the country, and delivering benefits to consumers. As well as their relevance for decarbonising the economy, we have evidence from our previous work that our selected technologies contain areas of existing strength for the UK. These technologies are:

- Tidal stream energy

- Carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS)

- Offshore wind

- Advanced nuclear

- Green hydrogen

- Grid flexibility and smart systems

- Buildings (including heating, cooling and building fabric)

By making the various trade-offs involved in the allocation of public support more visible, this work has potential to assist policymakers to make more informed choices when designing green industrial policies.

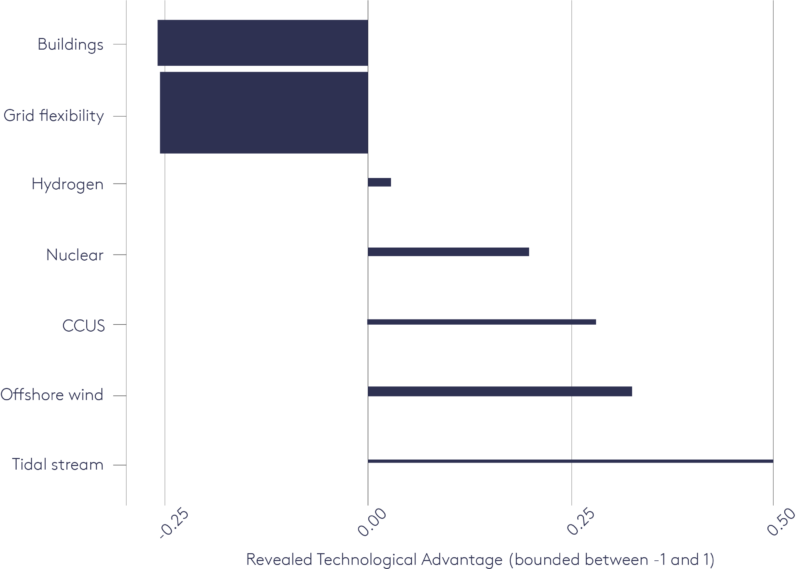

Indicative strengths: tidal stream energy, CCUS and offshore wind

Our assessments so far point to tidal stream, CCUS and offshore wind (particularly Floating Offshore Wind [FLOW]) as potential priority areas for green industrial policies in the UK. These are the UK’s top three strengths in innovation (see Figure 1) measured by patent data – a forward-looking indicator of growth opportunities that could be available if investments were made in a timely manner to translate technological specialisms into strong domestic supply chains. The three technologies already feature prominently in the Government’s clean energy ambitions, and their strong position within the UK’s technological capabilities is consistent with our earlier findings from 2022.

Figure 1. The UK’s Revealed Technological Advantage in selected technology categories, 2016–2020

Notes: Revealed Technological Advantage (RTA) compares a technology category’s share in the country’s total patenting to that technology category’s share in global total patenting. Positive values suggest that the UK is specialised in a particular category. Technology categories are adopted from our previous work in Curran et al. (2022) with some adjustments made to best reflect current technology areas of interest. Bar widths reflect global patenting volume in the given category.

Source: CEP and Grantham Research Institute analysis (work in progress)

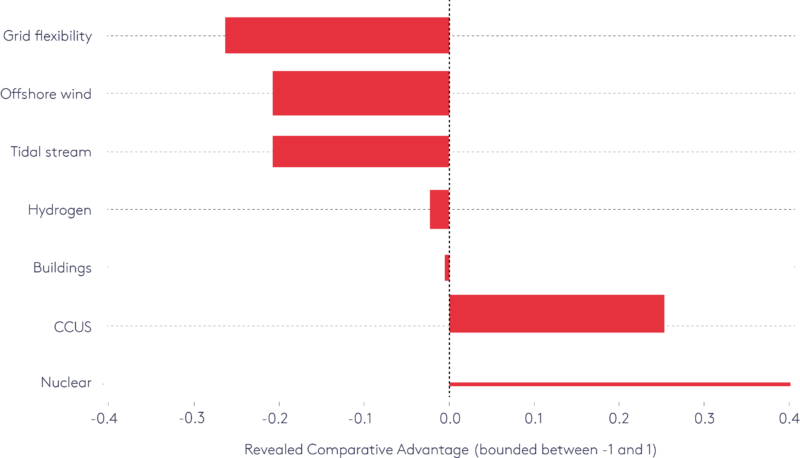

Turning to trade data, the UK has comparative advantage overall in exporting products relevant for CCUS but not offshore wind or tidal stream energy (see Figure 2). CCUS and tidal stream energy are both newly emerging sectors in which investments made now can help translate the UK’s innovative strengths into export capabilities. Offshore wind, on the other hand, is an established sector that presents a different story. The fact that the UK’s specialism in innovating in this area is not matched with a specialism in exporting relevant products, despite it being a global leader in deploying the technology, suggests certain supply chain opportunities have been missed. A more strategic approach to building supply-side capabilities could have led to more of such opportunities being captured, and is now necessary if the UK is to remain relevant in this ever-growing market.

Figure 2. The UK’s Revealed Comparative Advantage in selected technology categories, 2018–2022

Notes: Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) compares a product category’s share of a country’s exports to that product category’s share in global exports. Positive values suggest that the UK is specialised in a particular category. Product categories are adopted from our previous work in Curran et al. (2022) with certain adjustments and additions, drawing on the Green Transition Navigator and relevant technology reports from the 2019 UK Energy Innovation Needs Assessments. Bar widths reflect global trade volume in the given category.

Source: CEP and Grantham Research Institute analysis (work in progress)

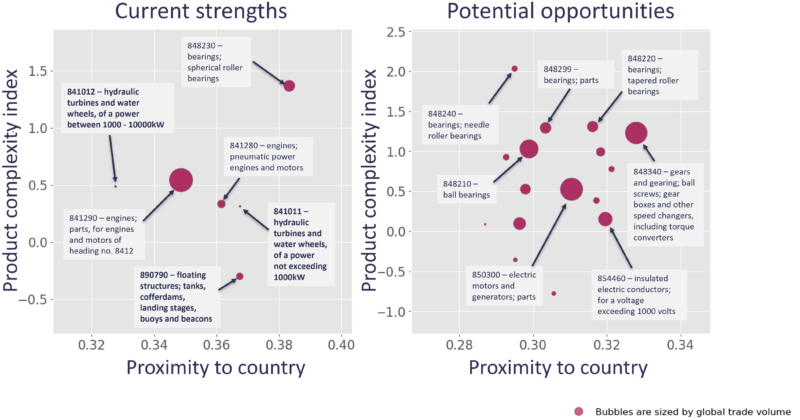

Furthermore, looking at the UK’s comparative advantage in a broad technology or product category (where each category is a grouping of relevant specific technologies or products) can mask important nuances and variations. For example, while the UK does not have revealed comparative advantage overall in offshore wind or tidal stream categories, it does have it in certain products within them such as floating structures and hydraulic turbines (as highlighted in Figure 3 below), which could represent high-value manufacturing opportunities.

Size of the potential pie and wider benefits to unlock

Both CCUS and offshore wind are already enjoying rapid growth in demand internationally, with earlier stage FLOW presenting a particular opportunity for opening up new markets by extending the application of the technology to deeper waters. Demand for tidal stream technologies is likely to be smaller and concentrated in a narrow set of regions around the world, but the UK could arguably capture a greater share of the global market given it starts from a clear position of leadership on deploying relevant technologies.

Beyond opportunities to be captured from international markets, there are various other ways the three technologies can contribute to a sustainable and inclusive economy in the UK. Investing in CCUS, offshore wind and tidal stream technologies is likely to generate jobs in the offshore economy, aiding a smoother transition away from oil and gas. Furthermore, investing in scaling up and further innovation in these technologies can enable technology cost reductions, in turn reducing costs for society. This can either be in the form of lower and less volatile energy bills, or as a reduction in the overall cost of the transition, which would in turn reduce the cost pass-through experienced by consumers from a whole range of products and services.

Making industrial policies forward-looking

Successful industrial policymaking would not only look at what an economy is already good at but also recognise and nurture areas in which it is well placed to become so – and evidence suggests this is most likely to be areas related to current specialisms. Providing indicators of relatedness, such as those introduced by Hidalgo et al., can therefore help policymakers target areas of ‘latent’ comparative advantage. Alongside this, indices such as the Product Complexity Index (a proxy for technological sophistication) enable products to be ranked in terms of their potential spillovers to the rest of the economy. For example, we have identified various types of bearings, gearing and parts of electric motors and generators within products relevant for tidal stream energy that rank highly on technological sophistication and represent latent comparative advantage for the UK (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The UK’s current strengths and potential opportunities relevant for tidal stream energy, 2018–2022

Notes: Each bubble corresponds to a specific product relevant for tidal stream energy defined by a six-digit code in the Harmonised System (an internationally standardised system to classify traded products). Product descriptions are shortened for the purposes of the chart. The horizontal axis displays country-to-product proximity (a measure of relatedness that is predictive of the probability of a country developing comparative advantage in a given product in the future). The vertical axis shows Product Complexity Index (a proxy for technological sophistication). The left-hand chart shows the products in which the UK has Revealed Comparative Advantage (i.e. ‘current strengths’). The right-hand chart depicts those in which the UK currently does not have a comparative advantage, but where it could build specialisation in the future (i.e. ‘potential opportunities’). Bubbles are sized by the global trade volume of the given product.

Source: CEP and Grantham Research Institute analysis (work in progress)

Such indices only present one part of the story, however, which should be interpreted with care and in combination with other indicators such as potential market size. Moreover, unrelated diversification – which some research suggests is a good strategy at medium to high levels of economic complexity – may require industrial policy support to a greater extent than related diversification does. Such bets are riskier, but could potentially offer higher rewards, and should therefore be considered as part of a portfolio of sectors to target.

What this all means for the new government

The Labour Party has long linked its approach to growth with net zero, adopting a mission to make Britain a “clean energy superpower” in its election manifesto. Within its first month in government, it has established Great British Energy and the National Wealth Fund as key institutions to support its vision for an active state that captures the complementarities between net zero and growth objectives. More work is now needed to operationalise these mechanisms as effectively as possible, ensuring that they allocate public support in such a way as to crowd in investment in domestic capabilities that maximise the country’s ability to capture green growth opportunities. Our evidence on the UK’s existing and latent strengths in the net zero economy can be particularly valuable to ministers and policymakers to this end.

Indeed, the three technologies – CCUS, floating offshore wind and tidal stream energy – we find as strong contenders for prioritisation are frequently cited by government as technologies of interest. This calls for a deeper understanding of the UK’s associated supply chain capabilities to be able to design relevant support most effectively. Such support for specific sectors and technologies under the Government’s new industrial strategy will need to recognise and address the specific market failures at play and be complemented with effective ‘horizontal’ policies, including on skills and long-term investment in innovation. In the face of fiscal challenges, the Government will also need to make the most of policy levers that do not imply significant spending, such as removing planning or other regulatory barriers and facilitating market coordination. The Industrial Strategy Council that the Government has committed to establishing will be important to facilitate a strategy that serves the country’s long-term growth and productivity objectives, and make it enduring through parliamentary cycles.

Final word

Designing effective green industrial policies requires juggling multiple objectives and navigating a large amount of uncertainty by weighing potential risks and opportunities, drawing on the best available evidence. Only by being up to the challenge and embedding these policies in an overall growth strategy will the UK have a solid chance to grasp ‘the growth opportunity of the 21st century’. We hope our work can assist this effort by strengthening the evidence base, with our full results due to be published later in 2024.

[i] Past outputs from the collaboration between CEP and the Grantham Research Institute include broad assessments of the UK’s green capabilities across a range of technologies and detailed assessments of specific technologies like zero-emission vehicles, carbon capture, usage and storage and tidal stream energy. Our work combines original in-house analysis with literature review.

[ii] The project team for the current work includes Pia Andres, Ralf Martin, Florian Munch, Maxwell Read, Esin Serin and Arjun Shah. Input from Anna Valero and John Van Reenen at earlier stages of the project gratefully acknowledged.