A first global mapping of rights-based climate litigation reveals a need to explore just transition cases in more depth

Annalisa Savaresi and Joana Setzer have identified more than 100 climate cases that rely on human rights arguments to promote action on climate change – but also a growing body of ‘just transition’ cases that are questioning the distribution of the benefits and burdens that the drive to net-zero is creating. To better understand how the transition can be inclusive and respectful of human rights, this new frontier of litigation requires deeper exploration.

To develop a clearer and more comprehensive appreciation of the role of human rights law and remedies in the climate crisis, there is a need to consider all rights-based litigation concerning climate action. Yet to date, a focus on rights-based litigation that aligns with climate mitigation and adaptation objectives has dominated in the academic literature. We have previously referred to these cases as ‘near side of the moon’ cases, as they have become increasingly well-documented. Meanwhile, details of climate litigation that does not align with mitigation or adaptation have been neither systematically collected nor analysed – these are what we call ‘far side of the moon’ cases and they represent a significant gap in knowledge that requires further research.

The near side of the moon – cases aligned with climate action

We analysed 112 cases that relied in whole or in part on human rights arguments, brought up to May 2021. Comparing their characteristics with trends in general climate litigation reveals some striking peculiarities in rights-based climate cases.

Geographically, rights-based climate cases have been predominantly filed in Europe, followed by North America, Latin America, the Asia-Pacific and Africa. Most cases were recorded in regions endowed with regional human rights bodies that historically have been sympathetic towards the use of human rights complaints to pursue environmental objectives. Roughly 13 per cent of rights-based complaints have been lodged before international and regional human rights bodies. In general, most climate litigation cases have been brought in the US, followed by Europe and the Asia-Pacific, and only a very small number of the total number of climate cases (0.7 per cent) were filed before international bodies.

Chronologically, rights-based climate litigation is a recent phenomenon, featuring more prominently since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015. Many of the cases are thus still pending. Of the 57 that have been decided, 56 per cent have found against applicants and 44 per cent in their favour, and not all of the court victories have been attributable to successful human rights arguments.

Applicants in rights-based climate litigation are typically individuals and groups – the main rights-bearers in law. This stands in contrast with general climate litigation, where corporate actors have historically initiated most climate cases, challenging regulations or the withdrawal of licences and permits. Defendants in climate cases are typically states and public authorities, who are the primary duty-bearers in human rights law. However, a small but rapidly increasing number of rights-based climate cases are specifically targeting corporations, asking domestic courts and non-judicial bodies to interpret corporate due diligence obligations in light of human rights law and of the temperature goal enshrined in the Paris Agreement. These cases have attracted considerable attention, due to their ground-breaking nature and potentially revolutionary impacts.

What kinds of rights and strategies?

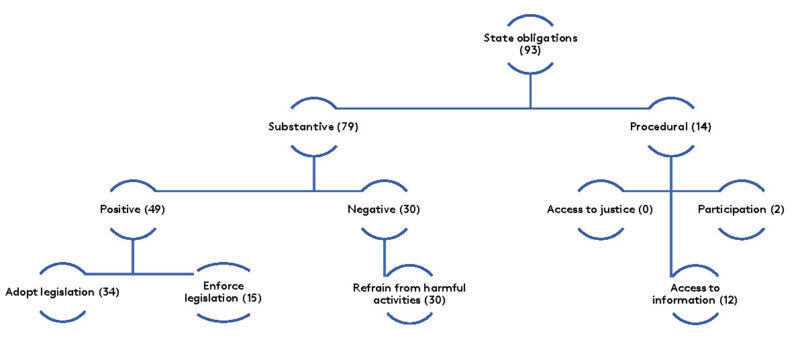

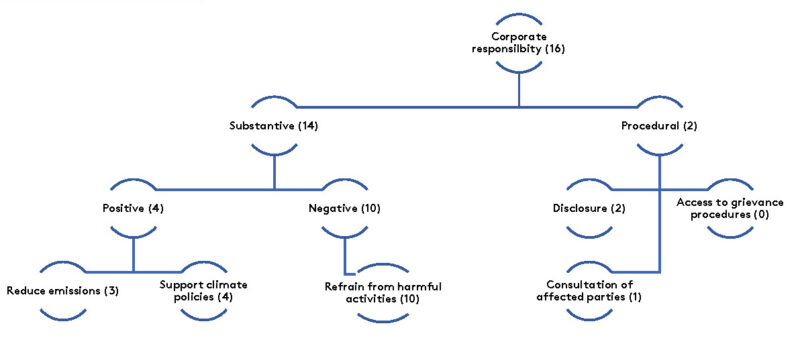

We have also identified the types of human rights most frequently invoked in rights-based climate cases against states (Figure 1) and against corporate actors (Figure 2).

Applicants in these cases often opt for a classic strategy in rights-based litigation: a demand for the fulfilment of substantive positive or negative obligation from states. Fewer cases rely on procedural human rights obligations.

Substantive positive obligations include asking states to take legislative and/or executive action to tackle environmental degradation that affects the enjoyment of human rights (e.g. Urgenda for mitigation and Torres Strait Islanders on adaptation) or demanding the enforcement of legislation (e.g. Leghari). In the case of Institution of Amazonian Studies v. Brazil applicants also requested the legal recognition of a newly articulated human right – the right to a stable climate system.

Substantive negative obligations include refraining from authorising activities or adopting policies leading to environmental impacts that violate the enjoyment of human rights (e.g. Nature and Youth and Greenpeace Norway v. the Government of Norway).

In rights-based climate cases brought against corporations, applicants typically argue that corporate actors have a positive duty to reduce emissions (e.g. Milieudefensie) or a positive duty to support, rather than oppose, climate policies and their enforcement (e.g. Carbon Majors inquiry). Applicants have also relied (sometimes simultaneously) on corporations’ negative duty to refrain from activities causing harm (the Carbon Majors inquiry being an example again here). Complaints relying on corporate procedural duties are scarce.

The far side of the moon – ‘just transition litigation’

There is a significant gap in our understanding of lawsuits in which human rights law and remedies are used to challenge measures and projects designed to deliver climate change adaptation and/or mitigation. In our paper we call these lawsuits ‘just transition litigation’, which we define as cases that rely in whole or in part on human rights arguments to question the distribution of the benefits and burdens of the transition away from fossil fuels and towards net-zero emissions.

Just transition litigation may marginally overlap with so-called ‘anti-regulatory’, ‘defensive’ or ‘anti’ climate litigation, but should be regarded as a self-standing type of litigation. Just transition litigation does not object to climate action per se, but rather to the way in which it is carried out and/or to its impact on the enjoyment of human rights. Examples include litigation targeting corporate actors and states for breaches of human rights obligations associated with the rights of Indigenous Peoples (e.g. ProDESK v. EDF). International human rights bodies have also received complaints challenging measures to reduce forest emissions and the construction of hydroelectric dams, alleging breaches of human rights in respect to culture, food, water and the rights of Indigenous Peoples, for example.

Applicants have also alleged breaches of the right to access to justice in the authorisation of wind farms (e.g. Fägerskiöld v. Sweden). Both the UK and the EU have been found to have breached their obligations under the Aarhus Convention for having adopted renewable energy laws and policies without adequate public participation.

This phenomenon of opposition to climate action on human rights grounds – which other scholars and databases have already identified but without analysing it systematically – is hardly a surprise. Fossil fuel-based economies may have created winners and losers but changing the status quo entails striking new equilibria between competing societal interests.Here, the notion of a ‘just transition’ has been invoked to highlight that the benefits of decarbonisation should be shared, and that those who stand to lose should be supported.

The rise of just transition litigation emphasises the importance of safeguarding both procedural and substantive rights, and of protecting individuals and groups from the arbitrary and unjust decisions of governments and corporations. Greater understanding of this litigation is necessary to appreciate the tensions associated with a transition towards zero carbon societies, and the ways in which they may be resolved through the adoption of a rights-based approach to climate change decision-making – as advocated for in the recent decision of the Human Rights Council to create a UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Climate Change.

Mapping the whole of the moon

As both climate legislation and litigation mature, an increasing number of rights-based litigation cases will focus on the enforcement of extant climate legislation and on the protection of procedural rights. Future human rights law and remedies will continue to be used to propel the energy transition away from fossil fuels, while also protecting those most affected by it. There is a need to explore the new frontier of just transition litigation to better understand how governments and corporations can address climate change and deliver net-zero emissions, and enact an energy transition that is inclusive and in line with human rights.

Webinar on 30 March 2022: This commentary summarises the main findings of the authors’ contribution to a special issue of the Journal of Human Rights and the Environment on rights-based climate litigation published on 28 March 2022. The special issue is being launched by the Center for Climate Change, Energy and Environmental Law (CCEEL) at the Law School of the University of Eastern Finland on 30 March, during which the authors will present their paper. Register here to join the webinar.

Annalisa Savaresi is an Associate Professor, Center for Climate Change, Energy and Environmental Law, University of Eastern Finlandand Joana Setzer is an Assistant Professorial Research Fellow in Governance and Legislation at the Grantham Research Institute. The views in this commentary are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Grantham Research Institute.