What is climate change litigation?

Different ways climate change litigation is defined

There are many ways to define climate change litigation, which is often referred to as simply ‘climate litigation’, but one point all definitions have in common is that cases must relate to climate change in some way. How direct and substantial this connection is generally indicates whether climate litigation is being defined along broader or narrower terms.

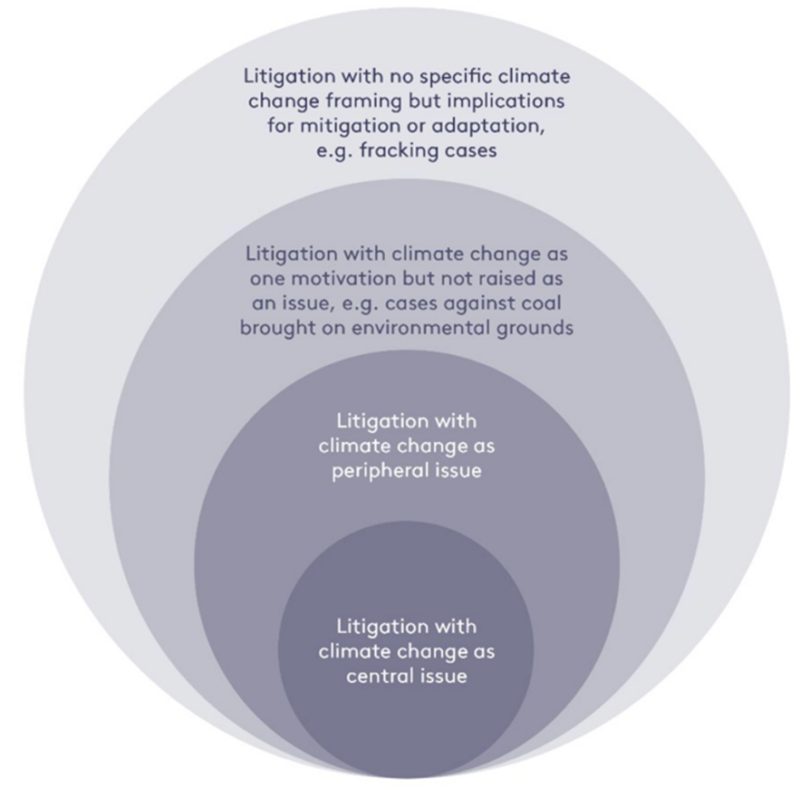

One way to visualise these definitional parameters is through Peel and Osofsky’s (2020) diagram of concentric circles (Figure 1 below). At the centre sits the narrowest definition: litigation that features climate change as a central issue in the case. An example of this is a case recently heard before the European Court of Human Rights, where applicants challenged the adequacy of Switzerland’s national climate policy response. Under the broadest interpretation in this conception is litigation that may hold implications for mitigating or adapting to climate change but that is not ‘framed’ along such terms (the outer circle). Examples include challenges to excessive gas flaring or industrial air pollution, where reducing emissions generated by the challenged activity is not a motivating factor for bringing the case but would be positive for the climate.

Figure 1. Visualising the definitional parameters of climate litigation

Source: Peel and Osofsky (2020)

Broader definitions have been criticised for creating ambiguity regarding which cases fall within scope. As climate change has economy-wide impacts, and many human activities influence climate change, a very broad approach could include almost any case in the world. Extracting any meaningful insights from such a large and heterogenous body of cases would be very challenging. On the other hand, narrower definitions may create regional imbalances in the corpus of climate cases. Cases filed in high-income countries of the Global North often tend to feature more explicit climate change arguments than those filed in emerging markets and developing economies in the Global South. Reframing definitional parameters around a typology of adaptation-related climate risks (such as droughts and flooding) could more accurately capture how litigation in some jurisdictions in the Global South is responding to the threats posed by climate change.

Is there a definition that is commonly used?

A widely used definition stems from the approach adopted by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University, which uses two criteria to identify cases for its Climate Change Litigation Databases: i) a case should have been brought before a judicial body (although certain examples of administrative matters or investigation requests are included); and ii) climate change law, policy or science must be a material issue of law or fact in the case. Cases in which climate change remains a peripheral matter and where climate-relevant laws and policies are not meaningfully addressed in the case argumentation are not included in Sabin’s databases. This definition is often adopted by academic researchers.

Regional climate litigation databases also exist and many of these tend to adopt a broader definition of cases. (These databases include the University of Melbourne’s Australian and Pacific Climate Change Litigation database; the Climate Litigation Platform in Brazil (JUMA) database; and AIDA’s Climate Litigation Platform for Latin America and the Caribbean database.)

Evolution of climate litigation over time

One of the first climate litigation cases was filed in the United States in 1986, contesting a federal agency’s decision not to evaluate the impact of its fuel economy standards on global warming. Over time, the litigation landscape has evolved, as a confluence of factors has created fertile ground for legal challenges to be brought against an expanding array of public and private actors. Some academics refer to three waves of litigation:

- The first wave began in the 1980s in Australia and the US, largely consisting of challenges to administrative processes that had failed to adequately assess what effects a policy or decision would have on climate change.

- The second wave, from 2007, followed an increase in public awareness of the consequences of climate change and more legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions after negotiation of the Kyoto Protocol.

- The third wave, from 2015, has seen a surge in litigation facilitated through coinciding factors such as the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015, developments in climate research, including Richard Heede’s ‘Carbon Majors’ report and attribution science, and the emergence of a transnational movement seeking to hold governments and private actors legally accountable for inaction on climate change. One of the most significant features of third wave litigation is the use of human rights and constitutional law arguments. The recent groundbreaking cases Leghari v. Pakistan, Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands, and Juliana v. United States typify this so-called ‘rights turn’.

Different types of cases extend across the three waves. For example, the administrative challenges that are characteristic of the first wave continue to be brought in many jurisdictions today, even as novel, rights-based cases are tested in the courts. However, while first and second wave cases focused on government and corporate actors most closely associated with contributing to the climate crisis (e.g. fossil fuel companies), third wave-style litigation is targeting private actors from an increasingly diverse range of sectors, including the food, agriculture and finance sectors. In parallel, the climate legislation landscape has evolved too, and inadequate or insufficiently ambitious laws and policies have frequently been the subject of legal challenges.

Are all cases supportive of climate action?

Some cases may align with advancing climate action goals while others seek to hinder or obstruct climate action. Labels such as ‘pro-’ and ‘anti-’ regulatory along with ‘pro-’ and ‘anti’ climate have been used to mark this difference. However, this distinction has become increasingly nuanced, as some cases may seek to challenge the way climate action is being carried out, rather than being opposed to climate action more generally. ‘Climate-aligned’ and ‘non-climate-aligned’ litigation have been proposed as alternative designations to recognise this nuance.

What types of behaviour might cases challenge?

In its Global Trends in Climate Litigation Snapshot report series, the Grantham Research Institute has developed a typology of the types of behaviour that cases seek to discourage or incentivise. These include:

- Government framework cases: those where applicants may challenge deficiencies in a national government’s overarching climate response or inadequate implementation of existing climate laws; see this example from Belgium.

- Climate-washing cases: those where statements made by public and private actors on contributions to climate action and the energy transition are challenged over their misleading or overstated nature; e.g. see this claim brought against the airline KLM.

- ‘Turning off the taps’ cases: those that challenge the flow of finance to projects and activities that are not aligned with climate action; e.g. see this case from South Korea.

Is climate litigation having a wider impact on climate change goals?

In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recognised that climate litigation has influenced the outcome and ambition of climate governance. A precise understanding of the scope of this influence is currently lacking but there is general academic consensus that litigation plays a significant role in inducing change in larger social movements, and that climate litigation can serve as a useful tool to hold actors accountable when they fail to take adequate steps to advance climate action. However, on its own, litigation cannot replace the laws and policies that are essential for driving ‘all-of-society’ approaches to transitioning to resilient, decarbonised economies by 2050.

This Explainer was written by Emily Bradeen, with review by Joana Setzer, Catherine Higham, Georgina Kyriacou and Sam Kumari.