Climate litigation is surging amid faltering politics and diplomacy

Less than a month to go until the COP30 conference in Belém, Brazil, political divisions are deepening and climate action stalling. Climate litigation is holding the fort in the fight against climate change. Tiffanie Chan and Joana Setzer write that with over 3,000 cases filed across nearly 60 countries, courts are shaping climate policy, enforcing human rights and challenging corporations.

Ten years ago, the Hague District Court ruled that the Dutch government must limit greenhouse gas emissions to 25% below 1990 levels by 2020. On the other side of the world, the Lahore High Court ruled that citizens’ rights had been violated by the government’s delay in implementing national climate change policy, unequivocally stating that “climate change is a defining challenge of our time”.

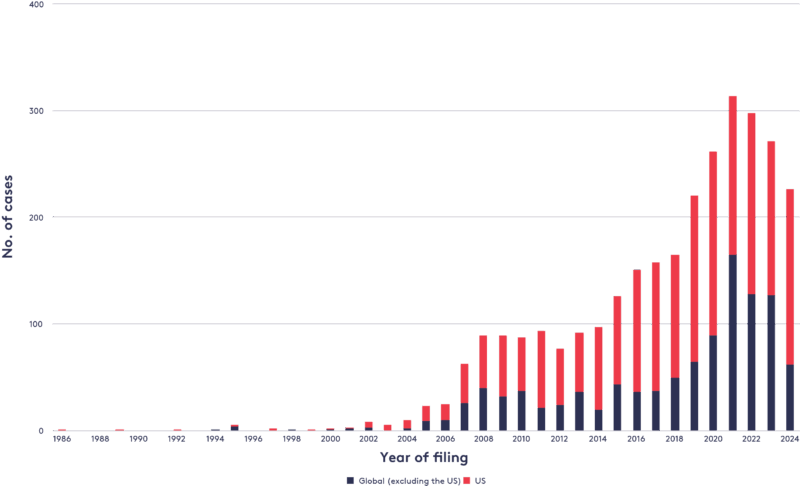

Since those rulings, the use of courts to drive climate action has accelerated. Over 3,000 cases have been filed across nearly 60 countries, reflecting how the law is increasingly being used to clarify responsibilities, demand accountability, and secure climate justice.

Over the past seven years, we have published annual snapshot reports in our “Global trends in climate change litigation” series. This year’s report highlights one key message: climate litigation is maturing and has entered a new phase, a more diverse and more complex one.

Figure 1. Number of climate litigation cases within and outside the US, 1986-2024

Climate litigation in the highest courts

The growing number of climate cases reaching apex courts (supreme courts and constitutional courts) globally signals an important moment in the evolution of climate litigation. Since July 2025, attention has rightly turned to the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) landmark advisory opinion on states’ obligations to tackle climate change.

The ICJ, often referred to as the “World Court”, confirmed that states must implement ambitious and timely mitigation and adaptation measures, including regulating companies and fossil fuels. Limiting the global average temperature increase to 1.5°C is a legal duty. Governments must act for the enjoyment of our human rights.

However, even before this, we were starting to see increasing evidence of climate law maturing around the world. Between 2015 and 2024, 276 climate-related cases reached apex courts: 117 in the US and 159 elsewhere. More than 80% of these cases involve governments, but cases against companies appear to have a higher overall success rate. Courts are delivering authoritative interpretations of how we must mitigate and adapt to climate change.

In times of political inaction, apex courts have offered a beacon of hope. Looking at the US state-level courts perhaps provides the most convincing example in our current political context. In December 2024, the Montana Supreme Court confirmed that the state constitution guarantees a clean and healthy environment, including a stable climate system.

Diversity of legal cases

Climate litigation is not just about what measures need to be taken in the future. It also serves as a crucial avenue to seek climate justice for harms caused in the past and present. Climate change was not caused equally, and its impacts are not felt equally. Our ability to cope also depends on past and contemporary patterns of wealth and power.

In 2024, 11 new cases were filed seeking monetary damages based on an alleged contribution to climate change harm through the emission of greenhouse gases or other activities. These are known as “polluter pays” cases. In May 2025, the Higher Regional Court of Hamm in Germany confirmed that in principle, major greenhouse gas emitters can be held liable under German law for the impacts of their emissions anywhere in the world. In this case, a Peruvian farmer alleged that RWE, a multinational energy company, bore responsibility for the increased flood risk from melting mountain glaciers near his home in Huaraz, Peru (see featured image).

As international negotiations on loss and damage stall, court rulings are providing a spark of hope for vulnerable communities facing devastating impacts from climate change.

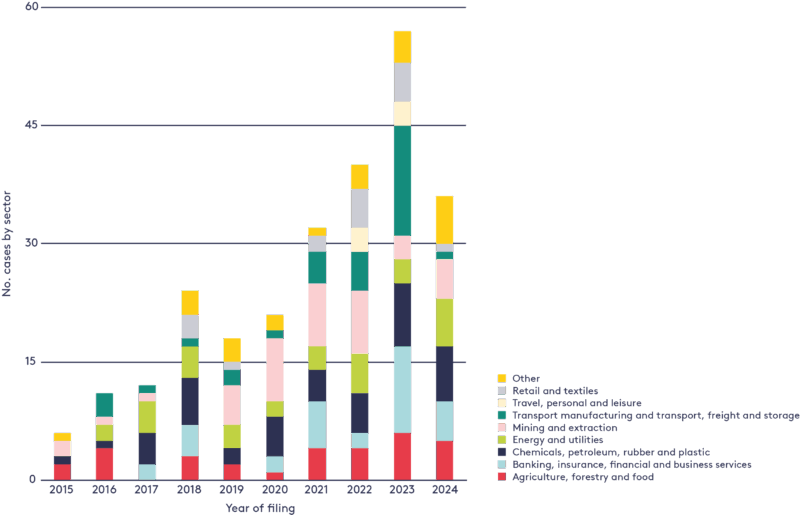

It is not only energy companies under scrutiny. Over the past year, new claims have targeted animal agriculture and associated food and retail industries, as well as professional services firms, signalling a widening circle or accountability.

Figure 2. Number of companies targeted globally in strategic climate-aligned cases by sector, 2015-2024

Adapting to a changing reality

As climate impacts intensify, courts are increasingly asked to assess whether governments and companies are adequately considering physical climate risks. Writing from the LSE, we witnessed the warmest summer on record in the UK. A summer temperature as high as 2025 has been made around 70 times more likely because of human-induced climate change.

Since 2015, 80 cases challenging a government or company for failure to take physical climate risks into account have been filed. However, not all cases are successful. In October 2024, a challenge to the UK’s Third National Adaptation Programme (NAP3), alleging that it was too vague and inadequately addressed risks, was dismissed. However, the case does not end here. The claimants are escalating the matter to the European Court of Human Rights.

Navigating complexity

Litigation seeking more ambitious climate action is only part of the story. We are also observing lawsuits being used to resist, reshape and delay climate policy. In 2024 alone, 27% of new cases (60 out of 226) involved non-climate-aligned arguments, and 88% of those were filed in the US. Sometimes, the same climate policy is being challenged from opposing directions, one arguing that it doesn’t go far enough to advance the transition, the other arguing it has gone too far and imposes a discriminatory burden on certain stakeholders, such as workers or consumers.

Courts are also being asked to mediate between climate benefits and competing environmental and social concerns. The Business and Human Rights Resource Centre tracks at least 60 cases globally relating to human rights and environmental harms in transition minerals and renewable energy projects.

These challenges are not about denying human-induced climate change. They contest the rules of the transition: who has authority to determine how fast we go, who bears the costs and what trade-offs are acceptable.

Amazon to courtroom

The host of this year’s COP is a country with a strong track record in climate litigation. To date, 135 climate cases have been recorded in Brazil. It is also leading the way for compensation cases involving climate damages for localised illegal deforestation, calculated based on an assigned monetary value to emissions per tonne of CO2 emissions.

As the world turns its attention to Belém, the host city, these cases highlight how legal systems in the global south are driving accountability and innovation in climate governance, often filling the gaps left by international negotiations.

This commentary was first published on the LSE Business Review blog on 15 October 2025 and has been reproduced here with permission.