Making the invisible visible: the impact of revealing indoor air pollution on behavior and welfare

Download

Indoor air pollution (IAP) levels can be much higher than outdoor air pollution and are linked to a range of serious and milder health outcomes, as well as reduced cognitive performance. Yet IAP is often overlooked in favour of policy attention on ambient air pollution. Given that people in developed countries spend around 90% of their time indoors, it is important to understand the degree of exposure to this form of pollution and, where it is high, ways that can be used to reduce it.

The authors of this paper design and implement a field experiment in London that monitors households’ IAP levels and then randomly provides real-time IAP information to a subset of them. They find that average baseline IAP is worse than ambient air pollution when residents are at home and that for 38% of the time, IAP is above World Health Organization standards. Additionally, lower-income households experience greater exposure than wealthier households.

Providing households with real-time feedback reduced IAP by 34% during occupancy time, as households mainly took action to increase their natural ventilation by opening doors and windows. The study also measures households’ willingness to pay to reduce IAP and to receive information about indoor air quality.

Key points for decision-makers

- The authors collected nearly 150,000 hours of data on indoor fine particulate matter (PM2.5), the US Air Quality Index (US AQI), temperature, and relative humidity over four weeks across 258 randomly selected households in the London Borough of Camden.

- They find that for 38% of the time, IAP is above World Health Organization standards.

- The many predictors of high IAP include smoking, income (exposure declines as income increases), certain household appliances (e.g. electric hobs are associated with higher levels) and dwelling characteristics (e.g. having more windows is associated with lower levels).

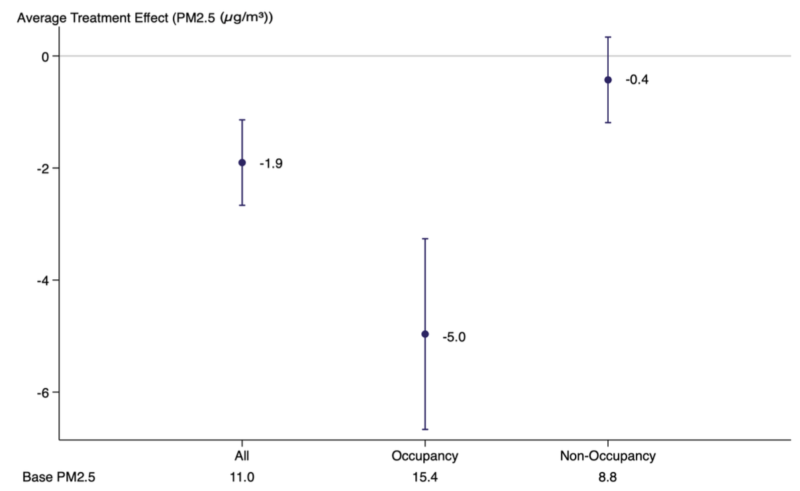

- Real-time feedback reduced IAP by 17% overall and 34% during occupancy time (see Figure 1). People used more natural ventilation as a result of the feedback and also changed their beliefs about exposure, realising it was higher than they had thought.

- Households were willing to pay for mitigation (reducing their exposure through purchasing an air purifier) rather than simply acquiring information about their pollution exposure.

- The authors calculate that subsidising provision of IAP monitors for all UK households could reach mortality savings amounting to nearly £40 billion. Furthermore, resultant increases in productivity would more than offset the upfront subsidy cost. In other words, subsidies for such technologies pay for themselves.

- The findings also have implications for energy efficiency policy, as measures to increase insulation can reduce natural ventilation. The authors call for solutions to this trade-off to be explored, to ensure a balanced approach that advances both climate and public health goals.

Figure 1 below shows that providing real-time indoor pollution information reduces overall pollution concentration by 1.9 μg/m3 (microgram per cubic metre), representing an effect size of 17.3% of mean PM2.5 of the control group post-treatment or 17.6% of baseline pollution (i.e. pre-treatment).

Figure 1. Average treatment effects (IAP monitor)