Why the UK Government has frozen fuel duty – again

Taxing petrol and diesel is one of the most important policies governments can use to combat climate change. However, the Conservative Government in the UK recently announced that fuel duty rates will remain frozen for the ninth consecutive year.

Fuel duty has not increased since 2010. During this period the volume of traffic has grown, producing more air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has calculated that the failure to raise fuel duty in line with plans originally set out by Chancellor Alistair Darling in 2009 now costs the Treasury around £9 billion a year. The UK’s Committee on Climate Change recently recommended that that the fuel duty freeze be ‘reconsidered’ if the country is to be on track to meet the fourth and fifth carbon budgets.

Given its myriad benefits, both current and future, why does the Government continue to freeze fuel duty? New research into the link between political competition and fossil fuel taxation offers insight into the Government’s decision-making. Spoiler alert: it is all about electoral incentives.

In times of high electoral competition, fossil fuel taxes do not rise

To better understand how politics drive fossil fuel taxation, we analysed petrol tax rates across 20 high-income democracies between 1978 and 2013. Petrol taxes are a very good way to examine the politics of fossil fuel taxation because they target a high-emitting sector and constitute a direct and highly visible price increase for voters that can be easily linked to government decision-making.

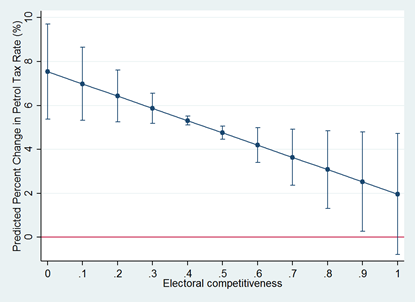

We find that governments tend to increase fuel tax rates when they enjoy a substantial electoral lead over their rivals. However, as this lead shrinks and political competition increases, governments tend not to increase rates. This negative relationship can be seen clearly in Figure 1. As electoral competitiveness increases along the horizontal axis, the predicted percentage change in the petrol tax rate from the previous year (the vertical axis) decreases. Moreover, the relationship is robust. It holds even after controlling for economic growth, inflation, governments’ fiscal health (debt and deficits), the international price of oil, government partisanship, the electoral cycle, urbanisation and a host of other potentially confounding factors. In times of high electoral competition, petrol taxes do not rise.

Figure 1. Changes in petrol taxes at different levels of electoral competition (source: author)

Note: Horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

The explanation for this result, we propose, has to do with political risk and democratic politics. When electoral competition is low, the governing party (or parties) enjoys a comfortable lead over rivals and a high probability of winning the next election. The opposite is the case when competition is high. Here it enjoys little to no lead and the outcome of the next election is highly uncertain.

The state of the electoral environment is crucial because it affects how governments gauge the political risk of potentially unpopular policies like fossil fuel taxes. Indeed, we assume that governments will tend to view directly increasing the price of a widely consumed good, such as fossil fuels, as generally unpopular with voters and therefore entailing some political risk.

When electoral competitiveness is low, governments can afford to lose marginal votes and still remain in power. This increases their willingness to tolerate such risk because it insulates them from any voter backlash that may result. Hence, it is in these moments that we observe them taking decisions to increase fossil fuel taxes. However, when their lead shrinks to a few percentage points and they are fighting neck and neck with the opposition, they have little incentive to tolerate more political risk. This is why they play it safe and leave tax rates where they are, or in some cases even lower them.

We focus exclusively on government decisions to directly tax fossil fuels consumed by voters. Whether the same political logic holds for other climate policy instruments is the subject of ongoing research – but we expect that it does.

The UK: political expediency over the environment?

The Conservatives are facing very stiff political competition at the moment. The party managed a razor-thin 1.4% vote margin over Labour in 2017’s General Election (the difference in the proportion of the two-party vote share between the parties – a statistic typically used to measure electoral competitiveness). This is the narrowest vote margin between the two parties since the 1970s. In political science, anything below a 5% margin is considered very competitive.

Opinion polls conducted over the last few weeks put the Conservatives anywhere from six percentage points ahead of Labour to two points behind. These numbers put the Government’s re-election prospects in serious danger. A very small shift in votes could spell defeat at the next contest.

In this high-risk electoral environment, our arguments predict that the Government will be very reticent to adopt policies they believe might upset a significant number of voters. In a country of diffuse petrol and diesel consumption, increasing fuel duty is precisely this type of policy. Indeed, transport is now the largest source of carbon pollution in the UK. Combined petrol and diesel consumption was 36.6 million tonnes in 2016, or around 752 litres per person.

Under these political conditions, freezing fuel duty is a low-risk electoral strategy and easy win. This is a crucial reason why the Government did it. It also explains why the Government is now actively publicising the monetary savings to voters, which it estimates at £1,000 for the average car driver and £2,500 for the average van driver since 2010.

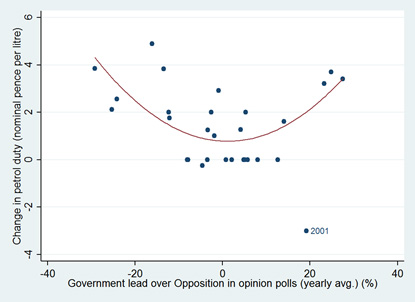

Apart from the 2019 budget, the long-term relationship between electoral competitiveness and fuel duty holds remarkably well in the UK (see Figure 2). From the early 1990s, there is a U-shaped relationship between changes in fuel duty and the Government’s lead over the Opposition in opinion polls. Fuel duty increases are smallest when polls are close (around 0 on the horizontal axis). This is where electoral competition is fiercest, and as a consequence the political risk of increasing fuel duty is highest. Political risk is lowest when the Government enjoys a substantial lead over the opposition and when it is lagging far behind. Indeed, it has generally been at these moments that fuel duty increases are largest. We find the same relationship in our study.

The one outlier is 2001. That year the Labour government substantially cut fuel duty rates in response to rapidly rising oil prices and subsequent fuel price protests in late 2000.

Figure 2. UK fuel duty changes and electoral competition over time (source: author)

Note: Fuel duty data is from the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Opinion poll data is from PollBase.

Political leadership needed

Increasing costs for motorists is politically difficult because it involves political risk. The Conservative and Labour Parties have been in a virtual dead heat in the opinion polls since the last General Election in May 2017. In an effort to retain, and gain, as many voters as possible, the Government seems to be playing it safe and not increasing fuel duty.

While politically expedient, the strategy is myopic. Focusing solely on the short-term monetary costs of fuel duty ignores its significant benefits, now and in the future. Indeed, fuel duty should be thought of a policy investment that transforms short-term costs into much larger long-term benefits – importantly, climate change mitigation.

In addition, the annual announcement that fuel duty will not rise in line with the escalator policy creates further policy uncertainty that can have a negative impact on investors and companies that are developing more fuel-efficient and electric vehicles. It is hard to reconcile the annual freeze in fuel duty with the need to rapidly decarbonise the UK’s transport sector.

If governments around the world are serious about decarbonisation they must show more political leadership, which at times means taking political risks.

Jared J. Finnegan is a PhD candidate in the Department of Government and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His working paper Changing prices in a changing climate: Electoral competitiveness and fossil fuel taxation is now published.

The views in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Grantham Research Institute.