Where next for the UK Climate Assembly?

The UK Climate Assembly’s recent report has revealed appetite among the public for an increase in the pace and scale of action to reach net-zero. Beyond the wide range of recommendations put forward by the Assembly, much can be learnt too from the process itself, argues Sophie Dicker.

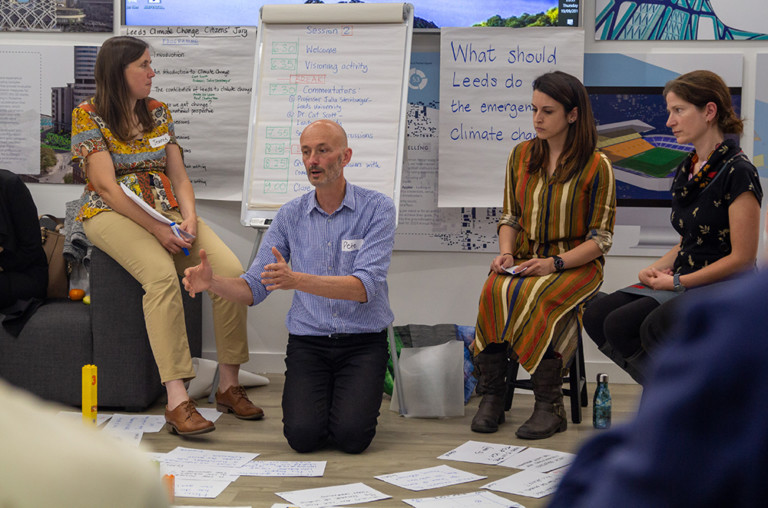

Earlier this month the UK Climate Assembly reported its findings on the question How should the UK meet its target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050? The Assembly was made up of a representative sample of the population, brought together to learn, discuss and make informed recommendations – an innovative approach in hearing from people across society on climate change. As we await a comprehensive government response to the Assembly’s recommendations, and to see if any will be incorporated into upcoming policy announcements, there is an opportunity to consider the ways in which the recommendations and learning from the process might be taken forward.

Positives of the Climate Assembly approach: challenging policy assumptions and building consent

The Climate Assembly has provided significant insight into which policy measures the UK public are likely to support – even to request – when they are sufficiently informed and engaged on issues relating to climate change. Members achieved a strong level of consensus across a broad range of policy areas which, if implemented, would mark significant steps forward on the path to net-zero.

Overall, Assembly members tended to agree that their understanding of and feelings about the path to net-zero had changed as a result of the process, and they backed recommendations that would entail significant cost and behavioural change. This included support for some politically contentious issues, including a frequent flier levy and reduced meat consumption – topics that even the most progressive politicians have often avoided discussing due to assumptions that they would be highly unpopular.

Assumptions of this nature are often used to shut down discussion and justify inaction; using models of informed participation like the Assembly could be a key way to overcome such assumptions. Indeed, although the views of the public, or specific groups of voters, are often thought of by politicians and policymakers as fixed, the Assembly process shows how opinions on complex issues can evolve through informed participation. Given the complex and at times controversial choices that will need to be made to reach net-zero, building popular legitimacy will be central. In fact, a recent Institute for Government report identified building and maintaining public and political consent as the defining challenge for achieving the 2050 net-zero target. The Assembly model, on a larger scale, could serve as a significant way to do this, as part of a broader strategy for public engagement.

The Climate Assembly model has also demonstrated its potential to address complex policy problems on a national level. Although an official evaluation of the model is forthcoming (in Spring 2021), initial results are encouraging. For example, 90 per cent of the 110 participants were found to agree or strongly agree that similar assemblies should be used more often to inform governmental and parliamentary decision-making.

The Climate Assembly’s influence on policy

Where the Climate Assembly model could be improved, however, is in its direct link to legislative, policy and funding decisions. In spite of the efforts of a number of MPs, including Select Committee Chairs, to promote and build on the findings, without the will of relevant Ministers to take them forward, they are likely to have little direct impact. To an extent the Assembly had this flaw designed in: it was commissioned by six Parliamentary Select Committees, with no mandate from, or direct link to, government. There are also longer standing, unresolved issues around how deliberative democratic approaches might best feed into the processes of a representative democracy, especially where competing recommendations are made.

The Government is therefore likely to take an approach of ‘cherry picking’ the recommendations that fit with existing plans. Research has shown that both contextual and recommendation-specific factors play a role in determining the chances of proposals being taken up from deliberative processes. These include factors such as the cost of a recommendation, the extent to which it challenges existing policy, and the degree of existing support within the relevant institution.

For example, it is likely that the Government will not engage with recommendations made by the Assembly that conflict with already-central components of the Government’s net-zero strategy, such as a heavy reliance on the development of carbon capture and storage technologies for fossil fuels (the Assembly’s stated concerns about CCS relate to the risk of carbon leakage and a continued reliance on fossil fuels).

Scope for developing the Climate Assembly model

To improve their potential to influence, deliberative models need to be better embedded into government and parliamentary processes. The Institute for Government’s recent report recommends that government departments build such approaches into the early stages of the policymaking process for net-zero. The Climate Assembly could trigger the start of this change, demonstrating the benefits of the approach and providing a template and key lessons. But there needs to be sufficient political and institutional interest, which is less likely while COVID-19 and preparation for the end of the EU-transition period dominate the policy agenda . However, the pandemic also raises the possibility of a significant opportunity to approach responses to crises differently – and alternative models of citizen engagement could be seen in a new light.

The model could also be used on a one-off basis to answer more specific questions or to develop specific climate change policy ideas for which it may be easier to secure a direct government mandate. For example, it could be applied to questions around climate change adaptation (raised by the Assembly but not focused on) or pension investments in relation to climate change (not mentioned by the Assembly).

The influence of similar assemblies in the future could also be strengthened if they were used to feed into existing influential bodies. For example, the Institute for Government’s report also recommends that the Climate Assembly model be developed into a permanent resource, hosted by the Committee on Climate Change, as a standing group of citizen advisers that can be commissioned by government or parliament to consider important net-zero policy areas. This is in line with a recommendation later made by the Assembly itself for a neutral body that monitors and ensures progress on net-zero, including citizens’ assemblies and independent experts.

The devolved administrations and local authorities could use similar participatory models, adapting them to their own contexts – indeed, such processes are already underway within a range of devolved and local bodies. For example, participatory processes could be positioned as a response to local declarations of a climate emergency, and designed to ensure a direct link to policy and funding processes. This could include adding innovative methods such as participatory budgeting to the existing Assembly approach. A range of local authorities have been engaged in deliberative processes with local citizens for a long time and have learnt lessons to be shared and built on. For example, Shared Future CIC (a community interest company) has produced a guide to support local authorities in commissioning citizens’ assemblies – funded by the Place-Based Climate Action Network (PCAN) – covering how these processes might address the climate emergency, and approaches to design and delivery.

Scotland’s Climate Assembly, due to kick off later this year, is mandated by the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019. The Act requires the Scottish Government to respond to the recommendations of any report produced by the Climate Assembly within six months, and as such is more directly accountable to Assembly recommendations than the UK Government is, at least formally, to the UK Assembly. Whether or not this will make a significant difference in how policy recommendations are taken forward, given that the obligation is only to respond, will provide greater insight into how to design influential participatory models. Deliberative processes on climate change in other countries, including in Ireland and France, will also have lessons to offer on design.

The need for leadership

In spite of the many positives, there were some areas among the Assembly findings that would have benefited from more effective leadership and communication to build a compelling case for change. The Assembly recommendations do not always acknowledge necessary trade-offs.

For example, the Assembly’s report shows unrealistic expectations about the level of electric vehicle usage likely to be possible across the UK, and recommends only small percentage decreases in car usage over the coming decades (of 2 to 5 per cent per decade). For comparison, the UK Parliament’s Science and Technology Committee found that widespread personal vehicle ownership does not appear to be compatible with significant decarbonisation. For this policy area, leadership is required to build an honest yet compelling narrative, developing the case for alternative forms of transport as well as measures such as localisation strategies (recommendations also suggested by the Assembly), instead of propagating the idea that driving levels can continue at similar levels to today’s while achieving net-zero, albeit with a switch to electric vehicles. The Assembly’s recommendations also allow for continued growth in the aviation sector (supported by as yet undeveloped low-carbon technologies).

Strong leadership on climate change is therefore needed alongside any future iterations of the Assembly model, to build a convincing case for potentially unpalatable trade-offs. At the same time, the Assembly model can be used to support such leadership, as a proven way of establishing informed buy-in from people across society and building legitimacy for measures necessary to meet the UK’s commitment to net-zero.

A version of this commentary was first published by Business Green.