Ukraine and the art of the (resources) deal

The proposed US–Ukraine critical minerals deal has important implications for climate action, not just geopolitics. Daniel Litvin gives five pointers for the deal, based on the experience of other natural resource agreements in unstable parts of the world.

A week after the blazing Oval Office row between Presidents Trump and Zelensky, the much-heralded ‘critical minerals’ deal between the US and Ukraine seems to be on the cards again – at least at the timing of writing.

President Trump’s interest in the deal clearly cannot be due to the important role of critical minerals in the energy transition. A sceptic on climate action, he will know that critical minerals are key inputs in the production of batteries, solar panel, wind turbines and electricity grids – a major increase in their supply will likely be needed to achieve net zero.

But he clearly sees their extraction as a big, and therefore worthwhile, commercial opportunity for the US. He will also have been briefed that they are important inputs to other strategic industries, including defence, IT and aerospace.

Europe, meanwhile, has an interest in critical minerals for explicitly climate-friendly reasons. It wants to make a big push to expand its manufacturing base for clean energy technologies and products such as batteries and electric vehicles (EVs). A flood of investment in mining Ukraine’s critical minerals could support this, by expanding raw material supplies on its doorstep.

For these reasons, the outcome of the US–Ukraine ‘critical minerals’ deal should be watched closely by those concerned about the climate, not just geopolitics.

And if the deal is to go ahead, there are some basic lessons to be drawn from other agreements over resources in other challenging parts of the world. These should certainly inform its implementation. The high-level observations below are drawn from my 20-or-so years of experience analysing and advising on such resource deals and projects. None of these projects were as headline-grabbing as the US–Ukraine deal, but many of the underlying patterns and themes are identical.

Put simply, striking an agreement over natural resources which proves genuinely ‘win–win’ over the long term requires a holistic, strategic, sober and sensitive approach. The current US–Ukraine deal has much to prove in this respect.

The architects of any such deal, I would argue, need to:

1. Build a joint fact base rooted in technical expertise, not inflated expectations.

Expert opinion suggests the US–Ukraine deal, as originally articulated, was based on wildly overblown claims about the extent and value of Ukraine’s critical mineral resources. This may have been intentional: to impress domestic US audiences. It may also have been due to misunderstanding of industry basics (for example, the technical difference between mineral resources and reserves).

Whatever the reason for the misapprehension, inflated expectations of benefits from resource deals have often been a cause of their unravelling over the long term. As reality dawns, parties feel cheated and seek to reclaim what they feel is owed. In countless cases, governments of mineral-rich countries, local communities around mines, and sometimes investors, have claimed to have been misled by mining companies who seemed to be promising great riches, leading to disputes and sometime outright conflict (see here and here and here for examples).

With the public’s only limited understanding of geology and resource economics, the mining industry is prone to overblown claims gaining popular traction. As Mark Twain is said to have quipped about mining, “The definition of a mine is ‘a hole in the ground with a liar at the top.’” From the perspective of the US–Ukraine deal, a period of sober, joint fact-finding seems an important next step to set a stronger basis for constructive collaboration in the months ahead.

2. Avoid getting hung up on minerals under the ground: focus on the broader minerals value chain.

The talk around the US–Ukraine deal to date has focused mostly on the potential profits from extracting the critical minerals under Ukraine’s soil. Such talk distracts from what is arguably a far bigger prize: the processing and refining of these minerals and their application in the manufacture of strategically important industrial components and products (such as EV batteries).

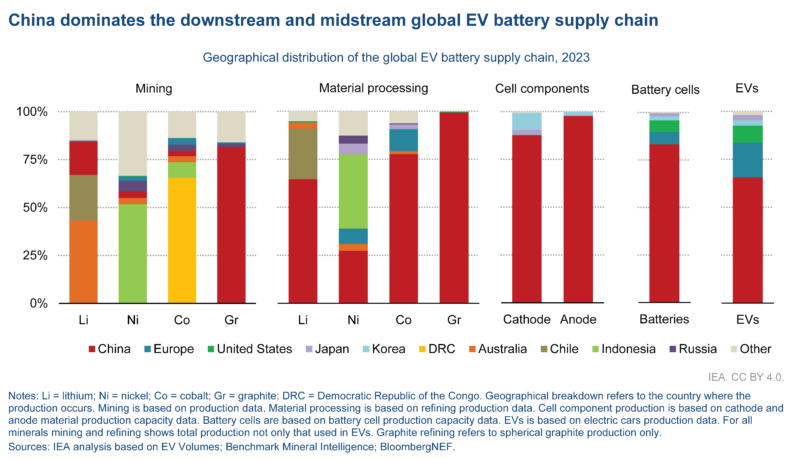

A big motivation for the US’s current interest in Ukraine’s resources is fear of Chinese dominance of the global value chains associated with critical minerals. But this Chinese dominance occurs more starkly in the refining and manufacturing segments of these value chains than in the actual mining of critical minerals (see chart below – the red denotes China).

Source: IEA Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024, page 30

This excessive focus on extraction reflects a common pattern in the politics of resources. Throughout history, major resource deposits have regularly attracted the attention of competing groups, each seeking to dominate and capture the profits that come from extraction. Meanwhile, less energy is devoted to devising collaborative approaches that might expand the value chain from using the resource concerned, even though the size of the prize here could be of a different scale. Ultimately, this is a harder task, requiring long-term vision, trust and strong institutions. Parties end up squabbling over a small pie, rather than jointly baking a giant one.

3. Understand that self-interest is served by a deal seen to be fair rather than unbalanced.

As first reported, the proposed US–Ukraine deal seemed to many observers (certainly those in Ukraine) as deeply unbalanced in the US’s favour. The US wants repayment from Ukraine for billions of dollars of past military support and was viewing critical minerals as a means to that end. Later reported iterations of the proposed deal appeared to leave open more room for mutual advantage. To ensure the deal is truly sustainable from both parties’ perspective, this more tempered approach will likely need further development and elaboration.

The history of big resource deals elsewhere in the world is again littered with examples of agreements later rewritten, or ripped up without compensation, as host countries and populations turn against foreign entities they view as profiting excessively or inflicting local environmental damage. Against such tides of popular resentment, contracts and legal defences often count for little.

During the 1960s and 70s, for example, a series of giant western oil concessions in the Middle East were successively revised and then effectively cancelled as countries in the region turned against foreign companies and powers they perceived to be ripping them off. This dealt a lasting blow to US and western energy security. In recent years, few major foreign-owned mining projects in developing countries have escaped periodic surges of such ‘resource nationalism’, which often have been interlaced with local environmental opposition, with some foreign miners only clinging on by their fingernails (see here, here, and here for example).

Today in Ukraine, the US would appear to have the upper hand in demanding what it wants in terms of critical minerals – but pressing home its advantage may serve it less well over the long run. Likewise, it should recognise that ensuring strong environmental and social standards around mines in which it has a stake is vital to its enlightened self-interest.

4. Avoid leaving security planning to later: that can invite trouble.

The US has so far avoided giving Ukraine clear security guarantees in return for access to its critical mineral revenues. That appears part of a strategy to encourage Europe to step up its military involvement. Instead, the US administration has suggested that the US’s proposed involvement as a commercial partner in Ukraine’s resources sector should in itself provide good security deterrence – discouraging Russia, for example, from breaching the terms of any peace deal by making grabs for more territory.

The experience of resource assets in other unstable regions suggests this may be optimistic thinking. Particularly if the US–Ukraine critical minerals deal begins to result in big profits in regions of Ukraine close to Russian controlled territory and with only light-touch security, Vladimir Putin may find it hard to resist wanting more.

Many foreign-backed resource projects in unstable regions have struggled in their early years to predict how the security context might evolve, underestimating how their commercial success at a later stage would attract attention from different violent groups. On a geopolitical level, likewise, there are many past cases of leaders of militarily powerful countries succumbing to the temptation to grab a slice of valuable natural resources located outside their current borders. Examples include Saddam Hussein’s invasion of oil-rich Kuwait in 1990, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro’s threatened annexation of an oil-rich region of neighbouring Guyana in 2023, and Rwanda’s current reported backing for rebel incursions in the mineral-rich eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

5. Consider ‘the deal’ as a potentially decades-long process.

The history of the most successful resource collaborations between countries, or between countries and companies, is one of periodic renegotiation of original deals over the space of years and decades, as each side listens and adapts to the other’s evolving situation and needs. China’s current position of strength in critical mineral value chains results from a multi-decade industrial strategy and a cumulative process of interaction and diplomacy with different mineral-rich countries.

A good example of a mature, successful collaboration between a global company and mineral-rich country is the half-century-long relationship between De Beers, the diamond firm, and Botswana, the source of many of its stones. The deal between the company and the country has been periodically renegotiated over the decades, generating increasing benefits for Botswana while still also serving De Beers’ interests.

Given the current bad blood between Presidents Trump and Zelensky, any such mutually advantageous, long-term partnership between the US and Ukraine may seem far off. But it is at least not impossible to imagine an eventual future in which Ukraine’s critical minerals comprise an important part in western manufacturing value chains – helping underpin the low-carbon energy transition, particularly in Europe – and both Ukraine and the US reap significant economic and geopolitical benefits as a result.

In short, amid the shouting, and short-term transactional focus, there is a genuine ‘win–win’ to aim for. The big challenge is that it requires vision, patience, listening, and adaptability on all sides to get there.

The commentary expresses the author’s personal views and not necessarily the views of organisations he works with or the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.