The Cali Fund: unlocking industry contributions to finance biodiversity conservation

The recent establishment of the ‘Cali Fund’ creates a mechanism for industries that commercially benefit from biodiversity to contribute to its conservation. Lea Reitmeier and Agata Makowska-Curran provide their perspective on why this agreement is groundbreaking and outline the contributions made by a multi-disciplinary team from LSE during its negotiation at the UN Biodiversity Conference, COP16.

Rather than being separate from nature, the stability and function of our economies is embedded in it. But biodiversity is declining faster than at any time in human history. And as species of birds, insects and plants become extinct we lose not only the beauty of the natural world but also the important genetic information it holds, creating a significant source of financial risk. Thus, a key task during the negotiations at last October’s UN Biodiversity Conference, COP16 was to agree how to ensure the fair and equitable sharing of benefits of genetic information. The resultant Cali Fund entrenches the notion that biodiversity is not ‘free’, with sectors from agriculture to biotech, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and AI asked to share the economic gains from their use of nature’s genetic information as early as this year.

Supporting benefit-sharing from digital sequence information

Genetic sequence information, referred to as digital sequence information (DSI) in policy discussions, is derived from organisms such as plants and fungi from mega-biodiverse developing countries. Details of an organism such as its DNA or RNA are then stored and managed digitally in databases. DSI is an asset of global economic significance; it holds immense potential for innovations in drug discovery, proteins and materials, with both the volume of data and its users growing rapidly. So far, however, the commercial benefits of its use have predominantly benefited entities from high-income countries, including pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, agriculture and the fast-growing AI sector.

This monopolisation of benefits has been the source of heated international debate, with some referring to it as ‘biopiracy’: a problem that has been recognised for some time, with the Nagoya Protocol of 2010 representing the first attempt at equitable sharing of benefits from physical genetic resources. However, that agreement did not cover DSI, which due to its intangible nature does not fall under the definition in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) of ‘genetic resources’. To address the emerging need to include DSI, a new multilateral mechanism for DSI-benefit sharing was established (decision 15/9) and a supporting global fund agreed at COP15 in 2022, which at COP16 was to become the Cali Fund. The Fund provides a mechanism to collect funds from DSI users and distribute them to DSI providers, including biodiversity-rich countries and stewards of nature, such as Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

LSE’s contribution to the Cali Fund’s design

Last September, experts from several departments at LSE including the Grantham Research Institute, LSE Law School and the Department of Accounting, along with external members of the LSE-funded Ocean Biodiversity Collective, notably One World Analytics, conducted a policy roundtable, presenting ideas to COP negotiators on how the global fund could be designed. The LSE model that emerged from these discussions on how to operationalise industry contributions to the multilateral mechanism has been published in two policy briefs and is rooted in three key principles:

- Pay Nature First: Contributions to the fund should be seen as a cost of doing business with nature’s resources, in particular when operating in the DSI space.

- Everyone Pays: Biodiversity is not a free asset, so contributions should come from a broad range of entities.

- ‘FRETAP’ Principles: Contributions must be fair, reasonable, equitable, transparent and predictable.

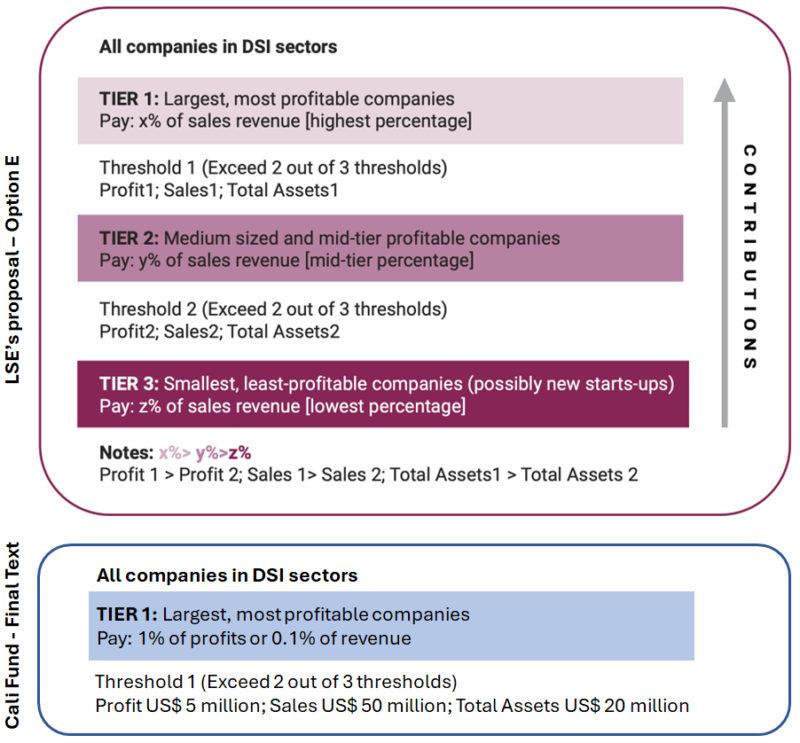

The starting point for the DSI negotiators at COP16 were the recommendations published in a CBD document last August, which included Options A to D as the proposed pathways for global fund contributions. Given the significant operational challenges associated with those, the LSE team proposed an alternative text option based on the tiered sales-based approach. This text was presented to negotiators on the first day of COP16 and later formed the basis of ‘Option E’, which was put forward by Norway, explicitly based on the LSE model presented earlier in the negotiations (see Figure 1). To ensure transparency and inform Parties further about the proposed approach, a joint LSE-Norway Technical Briefing Session was organised and included a robust Q&A on the basis of the LSE model.

The final CBD decision establishing the Cali Fund captures many of the aspects outlined in the LSE model which is now reflected in the text of Decision 16/2. Figure 1 presents the operative basis of the LSE model and visualises aspects of the final text.

Figure 1. Visualisation of LSE’s proposal (top) with an excerpt from the final text below

Source: Kamath et al. (2024) and CBD/COP/DEC/16/2 (2024)

An innovative tool to finance biodiversity conservation

The Cali Fund’s significance lies in its role as the only international mechanism to date that explicitly links the economic benefits industry derives from nature with its protection. It is crucial for mobilising resources from industry – a necessary component for reaching global financing targets. It is also an example of how the dependence of other sectors on natural resources could be linked to more formalised contributions to protecting nature in the future.

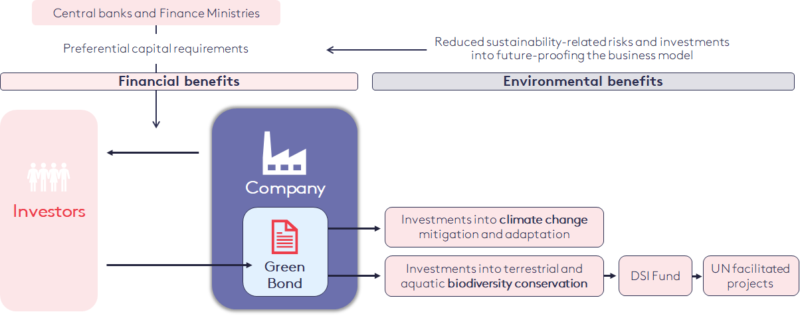

This, in turn, opens doors for private finance to acknowledge these contributions, for example through sustainable finance instruments. Governments and other stakeholders, including central banks, have opportunities to further support and amplify the impact of these mechanisms, making the Cali Fund pivotal in a move towards a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach.

Despite being voluntary, the proposed annual company contributions in the final decision 16/2 – 1% of profits or 0.1% of revenue – establish a precedent for industry accountability in biodiversity finance. The Cali Fund sets a benchmark for what companies should return to nature in exchange for the economic gains they derive from it.

As an agreement for the Cali Fund became more likely, industry representatives at COP16 began to push back. An unprecedented number of business representatives attended the summit and there was heavy lobbying from some sectors. While some companies expressed strong support for the Fund, resistance from certain sectors persists. For the Fund to be successful in attracting significant contributions to biodiversity conservation, it is vital that all included sectors are held accountable for making contributions.

National-level implementation to ensure timely contributions

Given the voluntary nature of the Fund, national governments should take measures to incentivise contributions. This could be achieved through:

- Comply-or-explain approach: National governments could introduce a ‘comply-or-explain’ approach to increase transparency and implementation, which would require companies to justify exemptions from contributions following certain criteria, placing the onus on entities to prove that they do not use DSI. At the EU level, experience has shown that while the REACH legislation mandates strict compliance with chemical safety requirements, it also incorporates mechanisms whereby companies can request authorisations for restricted substances or provide socioeconomic arguments for continued use, demonstrating how structured transparency requirements can enhance regulatory effectiveness.

- Sustainability reporting: Existing sustainability reporting frameworks like the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive could provide one avenue to increase transparency about a company’s DSI-reliance and Fund contributions. The omission of DSI information can reasonably be argued to influence investor decisions as it is a cost to the company and therefore falls within the International Financing Reporting Standards’ definition of materiality. Voluntary frameworks, like CDP, could provide additional guidance on disclosure.

- Sustainable finance: Contributions could be tied to sustainable finance instruments (see Figure 2) such as bonds or loans, which could help mitigate the systemic risks associated with biodiversity loss and offer reputational benefits and access to a broader investor base. Such instruments could be supported by central bank and finance ministry policies, like favourable prudential treatment in line with financial stability goals. Moreover, these policies also impose reporting obligations, providing a straightforward way to increase disclosure and thus supporting enforcement. The disbursement of the funds needs to take place in a transparent, robust and credible manner, to provide investors with the certainty that the money goes towards effective biodiversity conservation projects.

Figure 2. Linking sustainable finance instruments to contributions to the Fund

Source: Authors

Looking ahead, what is needed?

A central challenge during the negotiations was the difficulty in establishing the economic value of DSI. With very little analysis of its economic worth based on the quality and informational content of the asset published to date, determining an adequate volume for the Fund through a top-down approach faces significant data challenges. In the future, frameworks like natural capital accounting could help capture DSI’s value within global economic reporting systems such as the UN System of National Accounts, bringing essential transparency to the national level.

These improved reporting solutions, together with country-level compliance mechanisms, could support the effective monitoring, equitable allocation and long-term sustainability of the Fund. Reaching an agreement on the Cali Fund was a historic milestone; now it is crucial to ensure its implementation.

The views in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the host institutions or the Ocean Biodiversity Collective.

More information on the presentations and materials presented at the Global Biodiversity Finance Roundtable held at LSE on 27–28 September 2024 can be found here. The Roundtable received funding from the LSE Knowledge Exchange and Impact Fund, LSE’s Ocean Biodiversity Collective, NORAD, the Meridian Institute and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. The policy briefs referred to in this commentary are: ‘Identifying Ways Forward: The LSE Roundtable on Global Biodiversity and Digital Sequence Information’ and ‘A Tiered Sales-Based Approach: Digital Sequence Information and Monetary Contributions from Industry’.

The LSE team contributing to the roundtable and subsequent discussions held during CBD COP16 consisted of: Dr Siva Thambisetty, Associate Professor of Law, LSE Law School, and project lead on the LSE-funded Ocean Biodiversity Collective; Dr Paul Oldham, Founder, One World Analytics (LSE Anthropology, 1996), and co-lead on the Ocean Biodiversity Collective; Dr Saipriya Kamath, Associate Professor (Education), Department of Accounting, LSE; Agata Makowska-Curran, PhD student, Department of Geography and Environment, and Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment; Lea Reitmeier, Policy Analyst, Grantham Research Institute and CETEx; and Jasmine Kindness, Researcher and Data Scientist, One World Analytics (LSE Anthropology, 2018).