Pursuing inclusive climate action through climate change framework laws: examples from the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Finland and South Korea

Countries are increasingly enacting framework laws to guide their responses to climate change. Emily Bradeen and Kate Higham discuss lessons learned from updating the United Nations Environment Programme’s Law and Climate Change Toolkit, and how certain countries are developing framework laws to tackle challenges related to inclusivity.

In January 2024, Kosovo passed its first Law on Climate Change, joining a cohort of nearly 60 countries that are using climate framework legislation to guide their overarching responses to climate change. As framework laws proliferate, it is important to understand how these laws are responding to the governance challenges generated by climate change, particularly as new thematic areas emerge and acquire significance – such as inclusive climate action.

We were commissioned by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to review climate framework legislation from around the world and to inform the update of UNEP’s Law and Climate Change Toolkit. This project gave insight into how some countries are developing framework laws that address challenges related to inclusivity. Such laws may provide useful reference points for legislators elsewhere who seek to design climate laws for a more just and equitable transition.

Governing the climate emergency is no easy task. By its nature, climate change is a multi-faceted and complex phenomenon that poses constantly evolving, unprecedented threats to all life on Earth. In response to this, countries must undertake transformative actions to shift to decarbonised and climate-resilient societies within an urgent and ever-diminishing timeframe. Yet such deep societal reorganisation gives rise to a set of thorny governance challenges that governments need to overcome to ensure that their climate responses are effective. While responses must be context-specific, it has been argued that the challenges themselves are quite similar in nature and commonly relate to the need for coordination across levels of government and economic sectors; the high threshold of scientific and technical knowledge required to inform viable policy pathways; and management and alignment of a wide array of competing interests before strategies can be implemented.

Although there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to successful climate governance, many countries have opted to lay the foundation for these economy-wide transformations through the introduction of climate change framework laws, which are designed to counter at least some of the challenges detailed above. It is widely recognised that these laws play an important ‘agenda-setting’ role in a country’s climate response. In so doing, they outline the country’s overarching climate objectives, including the setting of net zero or other long-term emissions reduction targets; allocate responsibilities to various actors within the governance ecosystem; and frequently create new mechanisms and institutions (or revise existing ones) for administering climate policies and strategies.

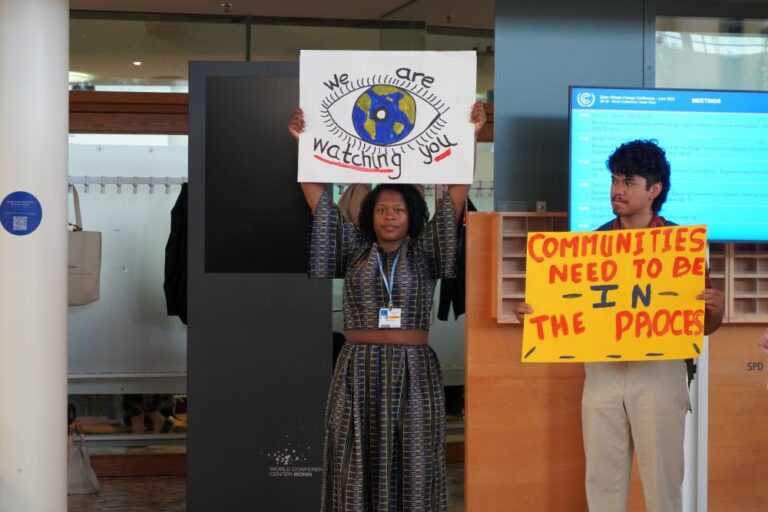

Ideally, a framework law should also draw on a climate politics narrative that resonates with the domestic public to improve the likelihood that the law will be implemented, in addition to avoiding potential backlash. This can be achieved in many ways but may involve engaging in deliberative processes in the hope they coordinate a wide array of competing interests. By aligning a more inclusive approach to whose interests are represented in their framework laws, legislators can set out a pathway for achieving decarbonisation and climate resilience alongside the pursuit of more just and equitable outcomes for all of society.

In our review of framework climate legislation for UNEP, we observed a few particularly interesting provisions that adopt inclusive approaches, some of which are highlighted below:

Embedding gender representation in climate institutions in the Philippines

It is widely recognised that climate change exacerbates gender inequality. To address this, some countries have sought to ensure that all genders’ perspectives are incorporated in decision-making. Section 5 of the Philippines’ Climate Change Act stipulates that the Climate Change Commission, composed of the President of the Philippines and three appointed commissioners, must include at least one woman as a commissioner. The Commission serves as an independent policymaking body for the government, and is tasked with coordinating, monitoring and evaluating all government programmes and action plans related to climate change. While this is by no means the only measure legislators should take to mainstream gender in framework laws, it is one example of how gender representation can be embedded into key climate policymaking bodies.

Recognising traditional landholders’ rights in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea’s Climate Change (Management) Act 2015 provides another example of how historically marginalised groups, such as indigenous peoples and customary landholders, can be included in decision-making around policy measures that affect their land and communities. The Act focuses on REDD+-related projects specifically: Section 89 stipulates that when entering into a climate change-related project agreement, both government actors and private individuals must obtain free, prior and informed consent from at least 85% of customary landholders who are residents on the land where the project is planned. Section 93(2) further specifies that “all affected landholders shall participate and benefit from the incentives of a climate change-related project implemented on land or at sea”. This serves as an important acknowledgement that indigenous groups should not only be participating in climate action but also benefit from how climate change is being addressed.

Integrating indigenous knowledge into policymaking in Finland

The assimilation of indigenous and traditional knowledge into climate action is one of the Paris Agreement’s guiding principles, yet this is embedded in very few framework climate laws. Finland’s Climate Change Act 609/2015 takes a comprehensive approach by mandating the formation of a Sámi Climate Council to act in tandem with the Finnish Climate Change Panel, the independent scientific advisory body supporting climate policy planning in Finland. Section 21 of the law requires members of the Sámi Climate Council to submit opinions on how Finland’s climate change policies can incorporate and reflect Sámi cultural needs, as well as producing assessments related to the impact of climate change on Sámi culture and rights. In addition to this, the law also stipulates that the rights of Sámi people to maintain and develop their own language and culture must be considered when climate policies are being prepared, and that policy negotiations must take place between the Finnish Government and Sámi Parliament. The Finnish example demonstrates how knowledge production can be designed to include and build on indigenous traditions, while also broadening mechanisms for the participation and representation of indigenous people in policymaking processes.

Planning for a ‘just transition’ to a decarbonised and climate-resilient society in South Korea

Several of the framework climate laws in UNEP’s Law and Climate Change Toolkit incorporate the idea of a just transition, which intersects with principles around climate justice and human rights. For example, South Korea’s Carbon Neutral Green Growth Framework Act embodies the concept of climate justice within the law’s guiding principles, and then translates this into practical measures on implementing a just transition-aligned pathway to decarbonisation. This includes Chapter 7 of the law, which outlines planning measures such as the preparation of a social safety net for groups that are particularly vulnerable to a transition away from carbon-intensive economic activities. Article 48 of the law stipulates the creation of ‘Special Districts for a Just Transition’, which can be specifically targeted with supportive measures, including means to attract financial investment and create new industries that align with policies around decarbonisation. This example illustrates how context-specific framework climate laws can integrate emerging concepts to proactively address and avoid foreseeable inequities associated with the energy transition.

International practice can inspire local, context-specific climate legislation

The initiatives outlined above constitute a small subset of the interesting provisions in a sample of framework climate laws, and will also feature as good practice case studies in the Toolkit. They highlight how some countries are incorporating specific requirements to address governance challenges and promote inclusive climate action. Although there is limited evidence of how these provisions function in practice, legislators around the world have much to gain from drawing on these examples of international practice for inspiration and adapting them to domestic contexts.

Find more information about climate laws and policies from all around the world in our Climate Change Laws of the World database