‘Fit for 55’ and implications for climate litigation in the EU

The sweeping measures proposed in the EU’s ‘Fit for 55’ package of climate legislation are without precedent and are set to have a transformative impact on Europe’s society and economy. However, in its current form, the package creates areas of legislative uncertainty from which litigation may arise in response, as Emily Bradeen explains.

EU legislators are in the process of approving landmark climate legislation proposed in the ‘Fit for 55’ package after two years of negotiations. ‘Fit for 55’ alludes to the EU’s revised climate target of achieving a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared with 1990 levels by 2030, and the measures proposed are designed to help achieve the climate objectives set out in the 2019 European Green Deal. Once the package is adopted, Member States will be responsible for transposing amended and new directives into national law, while EU regulations will apply directly to Member States.

Areas of legislative uncertainty

Four key areas of uncertainty currently stand out:

1. Enforcing and increasing the ambition of climate targets

Around the world, the number of court cases that seek to advance climate action by challenging the adequacy and ambition of governments’ national climate policies is growing, and represents a significant trend in litigation. Europe is no exception: more than half of these enforcement and ambition cases (so-called ‘government framework litigation’) have been filed in European jurisdictions.

Three avenues for legal challenges related to the enforcement and ambition of climate targets remain likely at the Member State-level:

- Domestic litigation could continue to be brought arguing that EU legislation infringes on rights guaranteed by national constitutions and international law. Globally, there are at least 58 cases questioning the level of ambition of climate targets, building on the arguments used in the landmark case of Urgenda Foundation v. State of the Netherlands. European jurisdictions may see similar challenges that seek to raise climate ambitions, even if Member States are compliant with targets set out in EU law.

- Domestic litigation might also seek to challenge the adequacy of national governments’ measures designed to implement the reforms introduced by the Fit for 55 package. Legal challenges may arise if national governments fail to adequately implement the policies outlined in their national plans, as in Notre Affaire à Tous et al. v. France, wherein claimants successfully argued that the French government created environmental damage by failing to introduce policies to meet France’s 2020 emissions reduction targets.

- Litigation could arise from a Member State’s failure to introduce framework climate policies required by Regulation (EU) 2019/199 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (the EU’s ‘Governance Regulation’). In September 2022, the European Commission issued formal notices to Bulgaria, Ireland, Poland and Romania over their failure to publish Long Term Strategies to address climate change, as required by the Governance Regulation. These or similar infringement proceedings could be heard by the European Court of Justice (CJEU). Civil society groups may also bring challenges against Member States if they fail to comply with the Governance Regulation, as in Greenpeace et al. v. Spain I and II.

2. Expansion of the EU Emissions Trading System

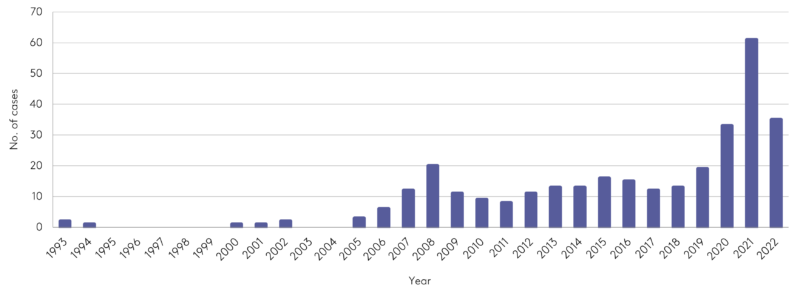

The proposed amendments to the EU’s Emissions Trading System (‘EU ETS’) Directive expands the current ETS to include greenhouse gas emissions from maritime transport and creates a second ‘parallel’ ETS to cover emissions from buildings and road transport. It is likely that corporations in these sectors will challenge the new ETS system, in a similar fashion to the spate of corporate cases that contested the EU ETS when it was first introduced in 2005, contributing to the overall increase in cases being brought post-2005 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of cases filed in European jurisdictions, 1993 to 2022

Furthermore, the proposed expansion of the ETS creates a ‘double regulatory burden’ for emissions from transport and buildings, which are already included under the EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), and so may lead to litigation from companies seeking to reduce their regulatory obligations. It is also possible that cases will be brought by Member States against the European Commission over the compatibility of national emission reduction policies with areas covered by the expanded ETS. And Commission-led infringement proceedings may be brought if Member States fail to successfully adopt and comply with the revised ETS Directive.

3. RED II and defining ‘low-carbon’ energy

The Commission’s original proposal for amending the Renewable Energy Directive (referred to as ‘RED II’) includes increasing the share of Europe’s renewable energy to 40% in its overall energy mix, although this target will likely increase to 45% following the REPowerEU Plan announcement. The proposed amendments to RED II include new provisions on bioenergy, which aim to prevent the degradation of carbon sinks and biodiversity loss that are associated with current practices.

However, controversy exists over how the amended legislation classifies bioenergy as a low-carbon energy source. Civil society groups have expressed concern that this framing may engender other ecological harm or counteract efforts to preserve biodiversity in the EU. Fraudulent statements and misrepresentations over the sourcing and procurement of bioenergy are another area of concern that could result in climate-washing litigation, a growing trend in litigation where false or misleading climate statements are challenged in the courts.

In its current form, RED II has been challenged before the CJEU, in a 2019 case over whether RED II would lead to increased impacts associated with deforestation (e.g. see EU Biomass Plaintiffs v. EU). At the national level, cases have also challenged the inclusion of biomass in RED II, given biomass’s adverse environmental and climate impacts (e.g. see Cooperatie Mobilisation for the Environment U.A. and others v. Executive Board of Province of North Holland).

4. Achieving decarbonisation through a just transition

Recent years have seen growing interest in ‘just transition’ litigation. In broad terms, just transition cases centre on the ‘fairness’ of climate policy measures. Cases may challenge the distributional impacts of new climate policies, such as how carbon pricing measures may disproportionately impact low-income households, or they may focus on procedural matters and access to justice, such as public consultations on renewable energy projects that may have negative social impacts on local communities.

While very few just transition cases have been filed in Europe, their volume is likely to grow, as aspects of the Fit for 55 package are expected to have a ‘regressive impact’ on low-income households, by increasing energy-related household expenses. Associated costs may not be completely offset by funds available to Member States through the Just Transition and Social Climate Funds, introduced by the Fit for 55 package to help alleviate the financial burdens the energy transition poses to households vulnerable to rising living costs. Challenges may also arise over how Social Climate Fund monies are disbursed at the national level, and what stakeholder perspectives are represented in decisions around funding disbursement.

Public and private sectors should take litigation into account

While global and European litigation trends indicate that other avenues for litigation against the Fit for 55 package certainly exist, the four areas outlined above are most likely to be the object of future litigation. National-level legislators and governments need to be aware of this litigation risk when transposing and implementing new and amended Directives in domestic law. The corporate sector, including legal and financial service providers, should also pay close attention to the measures proposed by the Fit for 55 package, given the complexity of obligations companies are likely to need to adhere to. Finally, civil society groups thinking about using legal routes to advance climate action have a role to play in highlighting gaps in the implementation of the EU legislation, and will need to consider where their legal interventions will be most effective.

This commentary is based on ‘Climate change law in Europe: what do new EU climate laws mean for the courts?’, a Grantham Research Institute policy brief by Catherine Higham, Joana Setzer, Harj Narulla and Emily Bradeen (published in March 2023).

The author would like to thank Joana Setzer, Catherine Higham and Georgina Kyriacou for their helpful review of this commentary.