Emissions targets in the oil and gas sector: How do they stack up?

In the last six months European integrated oil and gas majors have announced voluntary targets to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions that go beyond their own operational emissions. Importantly, these companies are acknowledging that Scope 3 emissions – emissions that are released downstream when their products are used (e.g. burned at a power plant) – should be part of their transition plans. This is significant progress for a sector that has long funded climate-denial research and lobbying.

Some of these companies are describing their climate targets as ‘net zero’. But are they? The devil is in the detail. Last month, analysis conducted at the Grantham Research Institute for the Transition Pathway Initiative shed light on how ambitious the recent emissions targets set by the six largest European majors really are.

Oil and gas’s journey

The fact that some oil and gas companies are setting targets for their Scope 3 emissions is an important shift in how these companies engage on climate change. The oil and gas sector has a rich history in lobbying against greenhouse gas regulation. Even since the Paris Agreement this has continued. Last year, InfluenceMap found that “the industry appears to have been successful to date in preventing any policy measures that may materially impact their ongoing business operations”.

Despite those efforts, the regulatory and political environment has changed since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015. Holding on to large interests in fossil fuels now comes with financial risks created by the possibility of climate action. Consequently, investors that hold assets in these companies need to understand how they will transition to a low-carbon world.

The signal from investors is starting to be received by oil and gas companies. In a first step, many companies started addressing emissions occurring within their own boundaries (direct, Scope 1 and indirect, Scope 2 emissions), but did not take responsibility for the emissions associated with the intended use of their products – i.e. the combustion of fossil fuels (within Scope 3). But downstream emissions from burning fossil fuels are the major source of emissions from oil and gas, accounting for roughly 70 to 90 per cent of lifecycle emissions from oil products and 60 to 85 per cent of those from natural gas.

European oil and gas companies are now feeling the pressure from European asset owners and managers – anticipating stricter greenhouse gas regulation to go along with the EU’s and UK’s net-zero ambitions – to take responsibility for Scope 3 emissions, as well as to recognise the need to decarbonise their products.

Progressively ambitious targets in Europe, but not ‘net zero’

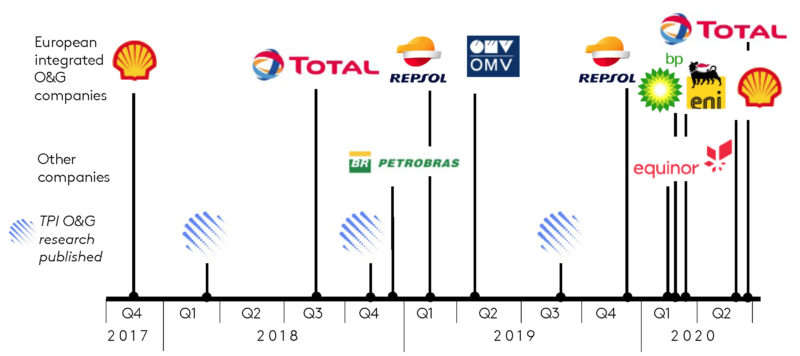

In 2017, Royal Dutch Shell was the first oil and gas company to embark on transforming into a low-carbon energy company. Its long-term strategy contains a quantified long-term ambition to reduce the company’s carbon emissions intensity, including Scopes 1, 2 and 3.

Since then, other European oil and gas majors have followed suit (Figure 1), expanding the scope of their emissions ambitions/targets to cover the full life-cycle of their products, and in some cases increasing their ambitions/targets. For example, Total’s most recent life-cycle target doubles the efforts it committed to previously. Despite this progress, it is unclear whether these company goals are aligned with the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement, which is what our research set out to assess.

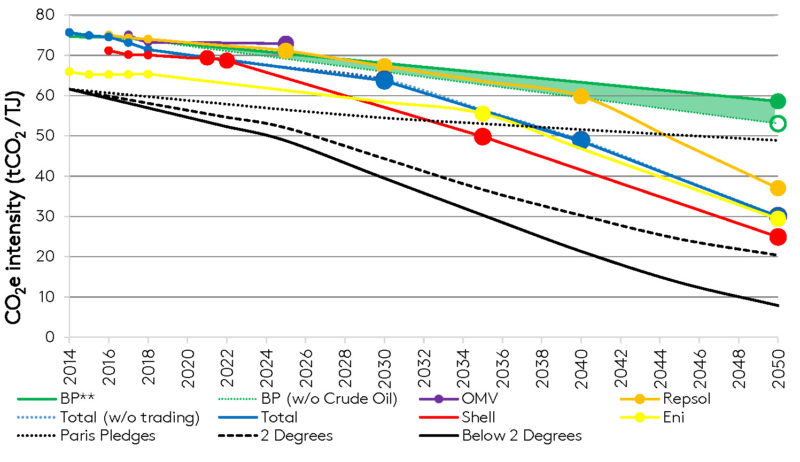

Each of the six European integrated oil and gas companies that has a Scope 3 emissions ambition/target has developed its own metric, making it difficult to draw comparisons. To make this comparison possible, TPI has developed a standardised methodology, which enables us to reconcile companies’ emissions targets using a common methodology. Figure 2 shows that European integrated oil and gas companies’ transition pathways are not equally ambitious.

* These assessments are made on a provisional basis. They have been reviewed by the companies, but, to maintain consistency of the data on the TPI website, will not be uploaded until we publish our next oil and gas assessments. ** TPI currently includes volumes from BP’s Crude Oil sales business in its assessment, which BP indicates exclusively comprises financial trading. TPI currently aims to exclude financial trading from its assessment, but can only do so where financial disclosure justifies it. The impact of excluding Crude Oil sales from assessed product is shown by the (lower) dotted line. A 2018 base year was used for BP, as not all the 2019 data were available at the time of publication.

The ambitions/targets set by Eni, Repsol, Shell and Total would be sufficient to align them with the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Agreement, i.e. countries’ voluntary pledges to reduce their emissions by 2030. However, it is well known that the NDCs are collectively insufficient to limit warming to 2˚C or below. Only Shell would be close to 2˚C alignment by 2050.

According to our metric, no oil and gas company would come close to being ‘net zero’ on a life-cycle basis. BP was one of the first companies to announce a ‘net zero’ emissions target. However, its ambition does not currently cover all the energy products it sells, and thus it falls short. Repsol’s ambition does not cover all its externally sold products either and the company is deferring the majority of the necessary emissions reductions until after 2040. For reasons such as this, while there is value in setting long-term targets, signalling a direction of travel to investors, some wonder how credible they are.

Intermediate targets can increase understanding of when efforts will be ramped up. Currently, only Total has shown a positive track record, expanding its renewables business and reducing its emissions intensity by almost 6 per cent over the past five years. However, over that same period Total’s absolute emissions rose by 8 per cent.

The role of offsets and absolute emissions reductions

The trend of adopting net-zero targets raises the question of how much companies will rely on emissions offsetting and how this should be viewed by investors. Currently, companies do not disclose enough information about their planned use of offsetting for us to assess the impact offsets will have on their targets. In its presentation to investors on March 4 2020, Shell indicated it might need to plant a forest the size of Brazil to offset remaining emissions. Other companies such as Eni have disclosed their intention to make extensive use of natural sinks too. This raises questions about the feasibility of offsets’ contribution to company targets, in particular whether offsetting will deliver genuine emissions reductions and if so at what cost.

A second issue is that an energy company can reduce its carbon intensity while still marketing fossil fuels. As long as growth in renewables sales is larger than growth in fossil fuel sales, carbon intensity will decrease. Although reducing emissions intensity by more than 50 per cent while still increasing fossil fuels sales is difficult, this shows that absolute emissions reduction targets are an important complement to intensity targets.

Eni has become the first oil and gas company that has done exactly that. In our view, Eni’s transition strategy is a good model in terms of its comprehensiveness and transparency, including a commitment to reduce its intensity by 55 per cent and absolute emissions by 80 per cent, while including disclosure on the expected contribution of offsets. It is just the overall level of ambition that may still be short.

Investor pressure needed in other regions

No oil and gas company can currently claim to have a transition plan aligned with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 2˚C or below. Nevertheless, the European integrated oil and gas companies are miles ahead of their non-European competitors. Last year we assessed 42 oil and gas companies headquartered outside Europe; none was aligned with TPI’s Paris Agreement benchmarks, and only one (Petrobras) had an emissions target that included Scope 3 emissions – which unfortunately seems to have been retracted recently.

European asset owners and managers have played a big role in influencing European oil and gas companies’ climate plans. For example, the Church of England Pensions Board and Robeco engaged with Shell, LGIM with BP and BNP Paribas with Total. Now it’s time for investors in other regions to step up.

The views in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

Read the full briefing paper, ‘Carbon Performance of European Integrated Oil and Gas Companies’, here: www.transitionpathwayinitiative.org/tpi/publications/58.pdf?type=Publication

Access the TPI tool for free here: www.transitionpathwayinitiative.org/tpi/sectors