What is rewilding and how is it relevant to climate change?

Rewilding is an approach to large-scale nature restoration and conservation that aims to reinstate natural processes and sometimes ‘missing’ species into landscapes that have been managed and/or degraded by humans, and in so doing, ensuring the richness of ecosystems is restored alongside resilience to drought, flooding and other severe weather events. Rewilding is increasingly being advocated to address both biodiversity loss and climate change, while also aiming to achieve a range of wider environmental and societal benefits.

Varying definitions of rewilding and views on how much humans should intervene

The wide range of definitions relating to rewilding, and its commonalities and differences with nature restoration and habitat management, makes defining rewilding difficult. Rewilding as an umbrella term can include a range of conservation activities, from unassisted vegetation colonisation on former agricultural land to the translocation of regionally extinct or comparable ‘proxy species’ (that perform specific ecosystem functions) to restore natural ecosystems. Key principles of rewilding usually include protecting and reintroducing keystone species (that help manage the entire ecosystem), removing invasive species, ending damaging practices such as deforestation or wetland draining, and restoring degraded landscapes (which have lost some degree of their natural productivity due to human activity).

Earlier definitions emphasised the reintroduction of keystone predators. In the 1990s, conservation biologists Soulé and Noss advanced a ‘3C’ approach to rewilding that advocated the creation of large cores (potentially more than 100,000 hectares/ha) free from human interference, corridors that link together cores, and the reintroduction of regionally extinct keystone carnivores, which manage ecosystems through predation dynamics. This system, it was argued, would support the transition of large swathes of land to a wilderness state said to have existed prior to extensive environmental modification by humans. As such, this definition of rewilding is best suited to geographical locations where there is enough land (at least 10,000 ha) for large herbivores to roam in relative isolation from human interference, and where the reintroduction of predators such as wolves does not adversely impact livestock.

While rewilding is conceptually aligned with nature-based solutions (NbS) – which aim to improve the sustainability of ecosystems while providing ecosystem services and resilience for humans and biodiversity – it is distinct from other NbS such as nature restoration in that it prioritises the intrinsic value of wildness, rather than specifically using nature to address societal challenges. Further, nature restoration approaches tend to target smaller areas because of the requirement to more actively manage the landscape and as a consequence tend to be more costly than rewilding.

There are proponents for ‘active’ and ‘passive’ rewilding approaches. Active approaches involve continued human intervention, restoring ecosystems and ecological processes through activity such as supplemental planting or re-naturalisation of rivers (e.g. reinstating their natural course). For others, the goal of rewilding is to move towards the removal of human influences entirely and in so doing support ecosystems to become self-sustaining through a passive approach: for example, when there are nearby seed sources to enable natural vegetation succession (whereby species in an ecological community change over time).

Although rewilding has become a more accepted conservation strategy over the last two decades, the methodological process, desired habitat size, management style (active or passive), and targeted outcomes remain under debate.

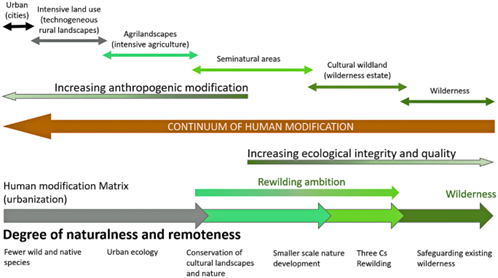

The wilderness continuum represented in Figure 1 illustrates the complexity of nature–human relations and the challenges of defining rewilding given the differing degrees of ambition and management interventions.

Figure 1. Wildness continuum (Source: Carver et al., 2021)

How rewilding can contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation

Because the nature and climate crises are interrelated, there is growing momentum to address both issues in an integrated manner. Advocates of rewilding assert the approach can do this by protecting carbon stores and boosting net carbon sequestration rates through restoring degraded environments – which at the same time has benefits for local biodiversity.

Understanding of the carbon sequestration dynamics across different types of rewilding is currently limited, posing difficulties in quantifying their climate mitigation potential. Nevertheless, a number of studies indicate that nature-focused land management approaches, particularly on degraded land, can yield sequestration benefits, delivering critical emission reductions and carbon removal to help countries meet their net zero targets, alongside improvements to the natural environment.

Examples of strategies to bolster carbon sequestration and therefore support climate change mitigation through rewilding include:

- Supporting vegetation succession on land currently used for livestock grazing, into mixed species successional forests, heathland and scrub, or reintroducing species-rich grasslands and floodplain meadows, which has the potential to enhance soil carbon stocks on degraded sites.

- Restoring peatlands and wetlands by elevating water levels and reducing grazing pressure, which can displace emissions from agriculture by beginning a transition to a net carbon sink.

- Restoring coastal habitats such as saltmarshes and seagrass beds, which not only sequesters carbon through vegetation and sediment processes, but also offers benefits for flood risk management, biodiversity, tourism and fisheries.

In terms of increasing resilience and adaptation to climate change impacts, rewilding increases ecological complexity and contributes to mixed landscapes with wetter areas, reducing the risk of wildfire. Expanding woodland cover and above-ground biomass decreases runoff and reduces downstream flood risk, as does rewetting wetlands and peatlands by enhancing water retention and slowing water flows. Re-naturalising river channels offers similar benefits, while reintroducing beavers can support natural flood management.

How widespread and popular is rewilding?

The number of rewilding projects is growing around the world, especially with the formation of networks like the Global Rewilding Alliance. Examples of projects in the UK include at West Sussex and Knapdale; further examples can be found in Australia, Chile, Mozambique, Kazakhstan, Portugal, Sweden and the US.

There can be opposition to rewilding where it could come into conflict with farming activity or other human uses of the land. For a rewilding project to be successful, there is recognition that it should not be introduced without engagement and buy-in from local communities, and projects that are designed to deliver socioeconomic and environmental benefits simultaneously are more likely to gain approval.

This Explainer was written by Leo Mercer with Sam Kumari and Georgina Kyriacou.