How can ‘blended finance’ help fund climate action and development goals?

What is blended finance?

Blended finance refers to the strategic use of public sources of capital to attract private investment in developing countries. It entails blending public capital such as Official Development Assistance (ODA) or funding by development financiers with private capital. Public funds are usually offered on concessional terms, i.e. terms more attractive than the prevailing market conditions, and are used to de-risk investment projects to mobilise additional private capital.

Private capital flows to low- and middle-income countries are often constrained by investors’ unfavourable perceptions of risk (actual or perceived). The risks of investing in emerging markets range from macro-financial risks (e.g. currency and inflation risk, credit risk) to political and regulatory risks (e.g. laws around investor protection, protection of property rights, unstable legal environments), to technical risks, which are particularly important in large-scale infrastructure projects (e.g. time and cost overruns). The public or philanthropic capital employed in blended finance transactions provides a buffer to such risks, making the investment more attractive to private commercial investors, thereby drawing in private capital that would otherwise not have been available – including finance for achieving climate goals and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The success of blended finance rests critically on the ability to maximise additionality, both in terms of the financial resources mobilised and the developmental impact created, while minimising concessionality, i.e. providing public capital at as close to market conditions as possible.

Why might blended finance be needed to help meet climate and development goals?

Progress on achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, including SDG 13 on climate action, remains insufficient. In 2015 the annual shortfall in the finance required was US$2.5 trillion and by 2022 this had increased to US$4 trillion. For comparison, in 2021 US$178.9 billion of foreign aid was provided by members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee.

Raising the finance to meet climate goals is particularly difficult for low- and middle-income countries. Developed countries committed to channelling US$100 billion per year to developing countries in 2009 but have so far failed to deliver on this promise. This gap in funding climate action is growing: a report published ahead of COP27 suggested that the investment needs for climate action alone in emerging markets and developing countries (other than China) total US$1 trillion per year.

The political nature of development assistance and the budgetary implications for donor countries mean that these financing gaps cannot be closed through increased aid alone. In international fora such as the G20, UN institutions, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the International Energy Agency, as well as in development finance institutions (DFIs), ‘blended finance’ is viewed as a promising tool to bridge the SDG and climate financing gaps by mobilising private sector investment.

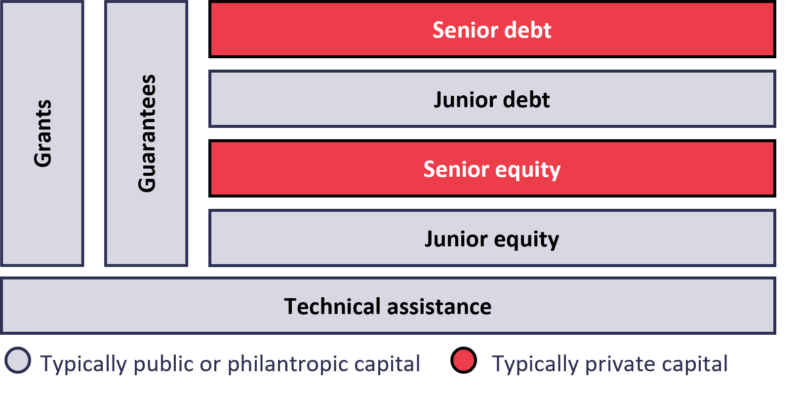

Figure 1. Common instruments used in blended finance transactions

There are several ‘instruments’ used in blended finance transactions, as shown in Figure 1 and described below.

Debt mechanisms: In 2020, concessional senior debt (e.g. loans at conditions more attractive than market terms but prioritised for repayment compared with junior debt) was the most commonly used instrument in blended finance transactions by members of the DFI working group. Debt instruments typically include loans, direct lines of credit and bonds. The Women’s Livelihood Bond, which pools loans made to social enterprises focused on empowering women in Southeast Asia, is an interesting example of a debt-based blended finance investment.

Equity mechanisms: When equity mechanisms are employed, investors take a share in the ownership of a corporation or a certain project and derive a claim on the residual value of cash flow streams after creditors’ claims are met. As in debt structures, there are typically senior and junior (subordinated) tranches. Senior investors’ claims are met first while junior investors’ claims are secondary. An example is the AfricaGrow Fund of the German development bank KfW and insurance company Allianz. This represents a ‘fund-of-funds’ structure, whereby the AfricaGrow Fund channels financial resources to African private equity and venture capital funds, which then select small- and medium-sized enterprises and entrepreneurs in Africa to invest in.

Senior vs. junior (‘subordinated’) positions: Blended finance mobilises private capital by altering the risk–reward relationship of private investors. When development finance providers such as DFIs take junior or subordinated positions they absorb higher risks, for instance by taking first losses compared to those (private) investors holding senior debt and equity positions. Under these altered risk–reward conditions, private investors view the blended finance projects more favourably and are incentivised to deploy their capital when they otherwise would not have.

Grant funding: This represents the provision of financial resources free of interest or provision of repayment. Grants help decrease the total funding costs of a given investment project and as such are sometimes used to make projects ‘investment ready’. A recent example is the Digital Invest Blended Finance programme by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which promotes investment in digital infrastructure in developing countries.

Guarantees: These can be defined as a type of insurance policy meant to protect financial institutions and investors from the risks of non-payment. They can be tailored to cover specific types of risk, which might be linked to the instruments for which they are used. Guarantees offer the benefit of not requiring immediate monetary outflows by donors, and preliminary evidence suggests that guarantees tend to be more effective than debt or equity instruments in mobilising private capital. An interesting example of the use of guarantees is NASIRA, a programme by Dutch development bank FMO which provides a guarantee for a portfolio of loans from local financial institutions to stimulate lending to underserved groups (e.g. women, refugees or young people).

Technical assistance typically represents grant-like resources used for project preparation as well as feasibility studies to ensure the quality, efficiency and sustainability of projects. According to data from early 2019, one-third of blended finance transactions to date have included technical assistance. The AfricaGrow fund mentioned above includes a technical assistance facility which is used to support funds and portfolio companies.

This Explainer was written by Timothy Randall with review by Hans-Peter Lankes.