Why sustainability means leaving behind old approaches to teaching finance

By Dirk Schoenmaker, Professor of Banking and Finance, Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam

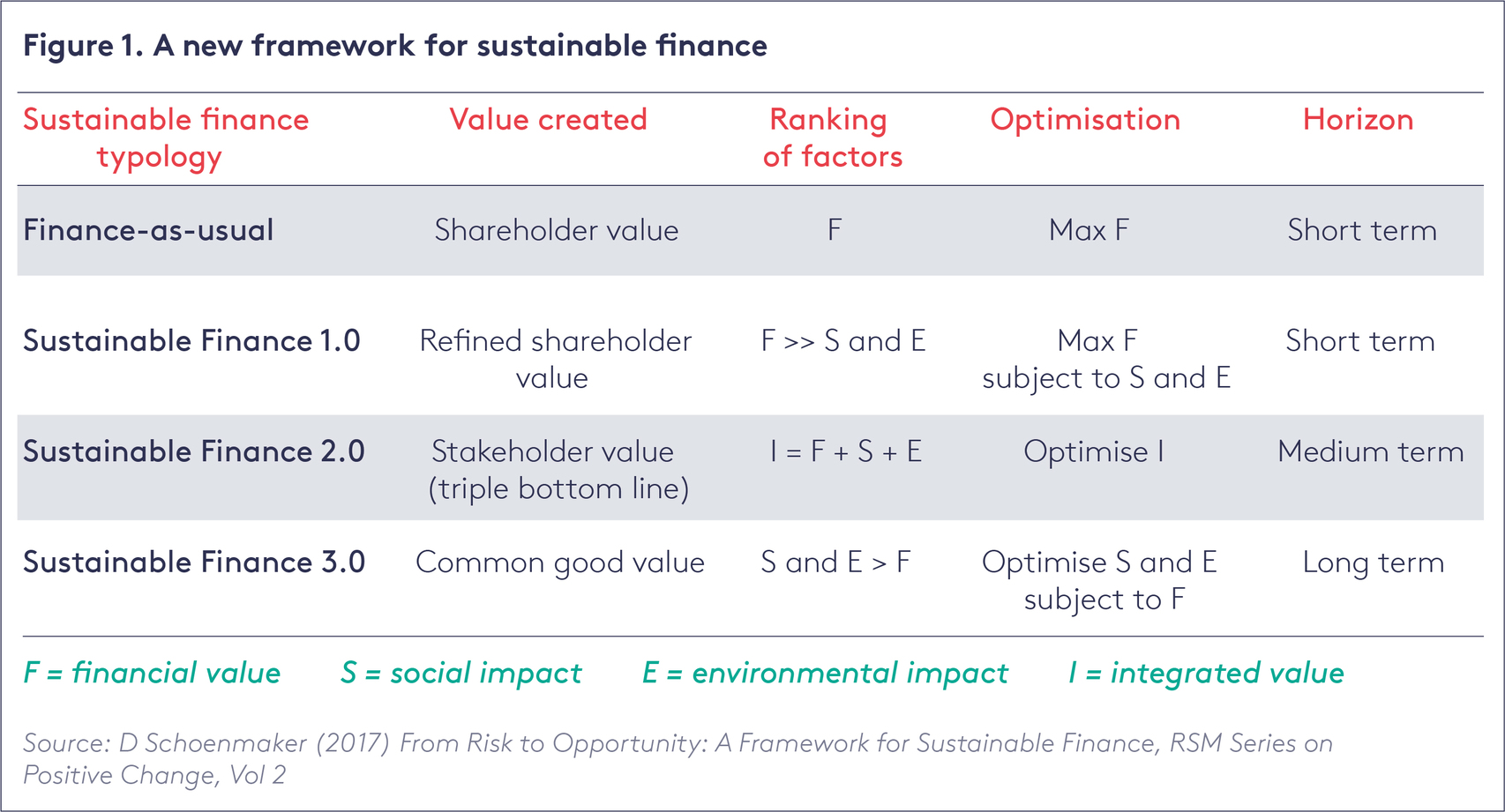

In this post for the Sustainable Finance Leadership series, Dirk Schoenmaker describes a novel approach to teaching the new generation of sustainable financiers. He presents a four-stage framework in which his favoured configuration, Sustainable Finance 2.0, monetises the social and environmental aspects, placing them on a par with the financial dimension.

Finance plays a crucial function in our economies. Asset managers and bankers take decisions daily on where to allocate their funds and where not. But they are operating in flawed markets that do not price natural capital or human wellbeing fully. In addition, they are rewarded by incentive systems that largely ignore long-term environmental and social factors. The result is a systematic misallocation of capital to activities that degrade the ecological and societal foundations of economic development.

This is not a problem only for today’s finance practitioners but for the next generation too. Finance textbooks tell students – the asset managers and bankers of the future – that profit maximisation is the guiding principle for these allocation decisions. Sustainability does not figure in this neoclassical environment, one that is still commonplace in most business schools and universities. In many respects, the talent of the future is also being misallocated through these obsolete assumptions.

Moving to Sustainable Finance 2.0

The good news is that there is agreement that we have to integrate the financial, social and environmental aspects. But the question is how we do this. A key insight from my research in sustainable finance is there are ‘varieties’ of sustainable finance.

Figure 1 summarises a new framework for sustainable finance involving four stages. In finance-as-usual, we just maximise profits (the F-dimension). In a more refined version of the shareholder value model, we pay some attention to social and environmental factors (the S- and E-dimensions), because that is instrumental to future profitmaking. It may be bad for the reputation of an investment fund to invest in so-called ‘sin’ companies that sell tobacco or cluster bombs.

My current favourite configuration is Sustainable Finance 2.0, where all factors are ranked equally. Social and environmental aspects are monetised, which puts them on a par with the financial dimension. The three dimensions can then be integrated and optimised (my new textbook, written with Willem Schramade, explains how).

Finally, we have the frontrunners, such as Hermes Investment Management and Triodos Bank, who are leading the way on Sustainable Finance 3.0. Impact investors and values-based banks put social and environmental impact first. Only when projects pass this societal hurdle do impact investors and bankers check the financial viability of the projects.

One of my students asked me: “Where are we today in this sustainable finance typology?” A fair approximation is that financial value still dominates, and social and environmental value is incorporated at, say, 10 per cent. This implies that we are just above, but still quite close to, Sustainable Finance 1.0. The real challenge is to increase the social–environmental value and make the move to version 2.0. In so doing, sustainable finance should move from being niche to mainstream.

Such a move to 2.0 would mean that all investors and bankers integrate the financial, social and environmental dimensions when they allocate their funds. Financial decision-makers would then help out in preserving ecosystems and respecting social justice. The frontrunners in 3.0 would lead the way in financing renewable energy, biological farmers, and responsible garment producers. These financiers are already avoiding fossil fuel companies for not being future-proof. Sustainable Finance 3.0 works from a vision of the long term inspired by the Sustainable Development Goals – the global strategy for sustainable development which makes clear that we must transition from business-as-usual to a sustainable economy – and only finances those companies that have a positive impact on the Goals.

Growing the next generation of sustainable financiers

Three years ago, I embarked on embedding these insights into my teaching of the next generation of finance students, by teaching a course on sustainable finance – without, of course, an established and trusted textbook.

Luckily, I work in a business school, Rotterdam School of Management at Erasmus University. My sustainability colleague suggested that I should explain the environmental and social challenges in detail. He introduced me to the work on planetary boundaries by Will Steffen and others and to the social foundations of Kate Raworth. Their studies underpin the Sustainable Development Goals.

In moving from business-as-usual to a sustainable economy, central banks can green their monetary policy operations. That means that the European Central Bank, for example, would buy more corporate bonds of low-carbon companies and less corporate bonds of high-carbon companies (such as fossil-fuel companies or traditional carmakers).

This transition is happening in the real world of companies. My business colleague explained the crucial role of a company’s strategy and business model to foster ‘sustainable business practices’. The good news is that asset managers and bankers can analyse companies’ business models and strategy.

As an example, at the School we created a case study on Dutch medical technology company Philips. This kind of analysis takes time and effort, but is doable. It is also fundamental because an environmental, social and governance (ESG) rating will not suffice. These ratings are too general and superficial to really catch what is going on inside companies; material ESG factors differ by industry. Moreover, sustainability transition is about the future (are companies preparing themselves for the transition to a sustainable economy?), while ESG ratings are typically based on historical data. Some early adopters of sustainable investing, like the Swedish pension fund Alecta, show that such a strategy can yield good investment returns. Alecta has a five-year average return on its equity portfolio of 14 per cent.

Leaving current approaches to finance behind

With all these theories and frameworks, we are now ready to enter the world of investing and lending. As a starting point, we have to leave current approaches (as taught in traditional finance textbooks) behind us. Conventional investing is built on the premise that markets are efficient (all information is reflected in stock prices) and portfolios should be fully diversified. However, we have learned that we need to investigate a company’s business model to truly understand how sustainable it is.

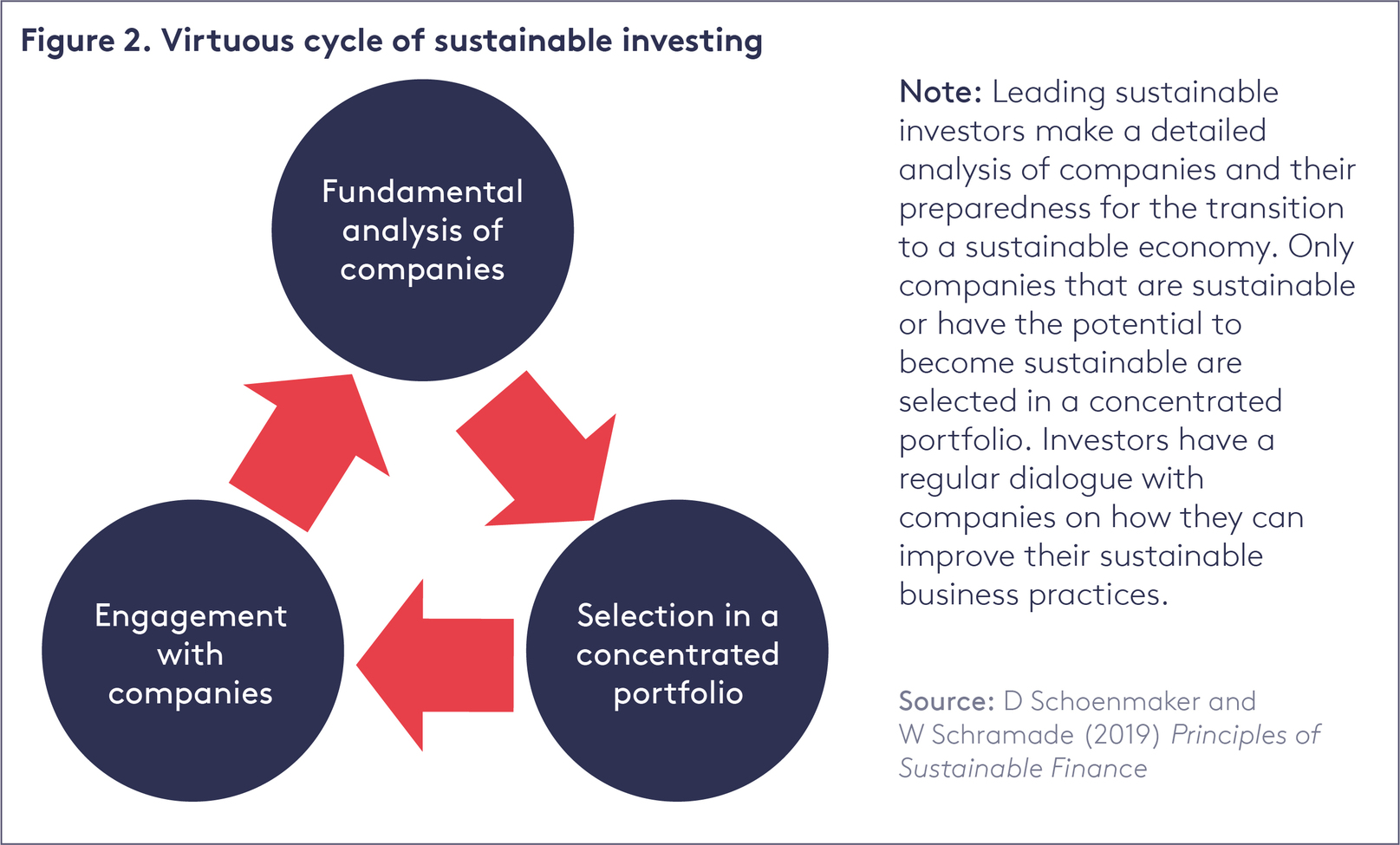

Andrew Lo’s adaptive markets hypothesis shows that information enters stock prices at the speed of human thought. How fast ‘sustainability’ information is incorporated into stock prices depends on the number of analysts and the quality of their learning. Portfolio managers can only analyse 50 to 100 firms, which suggests concentrated portfolios. They make not only the cost of fundamental analysis, but also reap the benefits of their information advantage. While normative finance theory tells us that we have to diversify an investment portfolio over the full market (passive investing), positive finance shows that diversification benefits diminish after 100 stocks.

A final element in this active investing approach is engagement with companies. This should be performed by the investor teams themselves – not by a separate sustainability department – to ensure they have this expertise in the team.

We now get to the virtuous cycle of sustainable investing, shown in Figure 2.

This is nothing new for bankers. They are already used to studying a company’s business model when assessing a loan application. And they ‘engage with’ their clients on a regular basis. The only new dimension is that they have to enter the social and environmental dimensions in their credit risk assessment. That means incorporating their findings on a company’s preparedness for the sustainability transition in the credit assessment.

How have our students reacted?

So now you have an idea of the key ingredients of the new textbook, Principles of Sustainable Finance. But what happened to the students? Before the course, they were not aware of the link between finance and sustainability. As they had to apply sustainability to real companies (using valuation techniques and scenario analysis), and as open, forward-thinking millennials, they quickly adopted the new way of thinking, providing plenty of positive feedback on the course. However, several students reported being surprised by the traditional finance thinking of the financial institutions they interned at. It is our hope that after they graduate they can apply Sustainable Finance 2.0 – and eventually 3.0 – and make it the new mainstream.

Our approach towards teaching finance needs to adapt quickly. This requires, first of all, a change of mission and an update of curricula at business schools and universities. At Rotterdam School of Management, our new mission is ‘A force for positive change’. And it requires a new mindset of academics moving beyond GDP and profit and using upgraded textbooks.

The views in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

Grantham Research Institute sustainable finance event with Dirk Schoenmaker

Professor Schoenmaker is taking part in a seminar on Wednesday 10 July, 12.30-2.00pm, in which he will discuss his new book Principles of Sustainable Finance (co-authored with Willem Schramade and now available from Oxford University Press) with Professor-in-Practice Nick Robins offering an LSE view as a respondent. Please email William Irwin if you would like to attend.