How ready is South Africa for a new fuel levy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

This June, South Africa’s much-delayed carbon tax is due to be implemented. Surprisingly, the 2019 budget speech announced it will take two different forms, which will come into force five days apart.

In addition to the expected direct tax, which is applied to the combustion of fossil fuels from eligible taxpayers (i.e. large companies), and which will cover around 60 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions in the economy, or around 400 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) a year, there is to be a carbon tax fuel levy. This levy will be applied to liquid fuels from 5 June, focusing on encouraging emissions reductions in the transport sector. Emissions from road transport currently account for around 7 per cent of South Africa’s greenhouse gas emissions, approximately 51 MtCO2e a year.

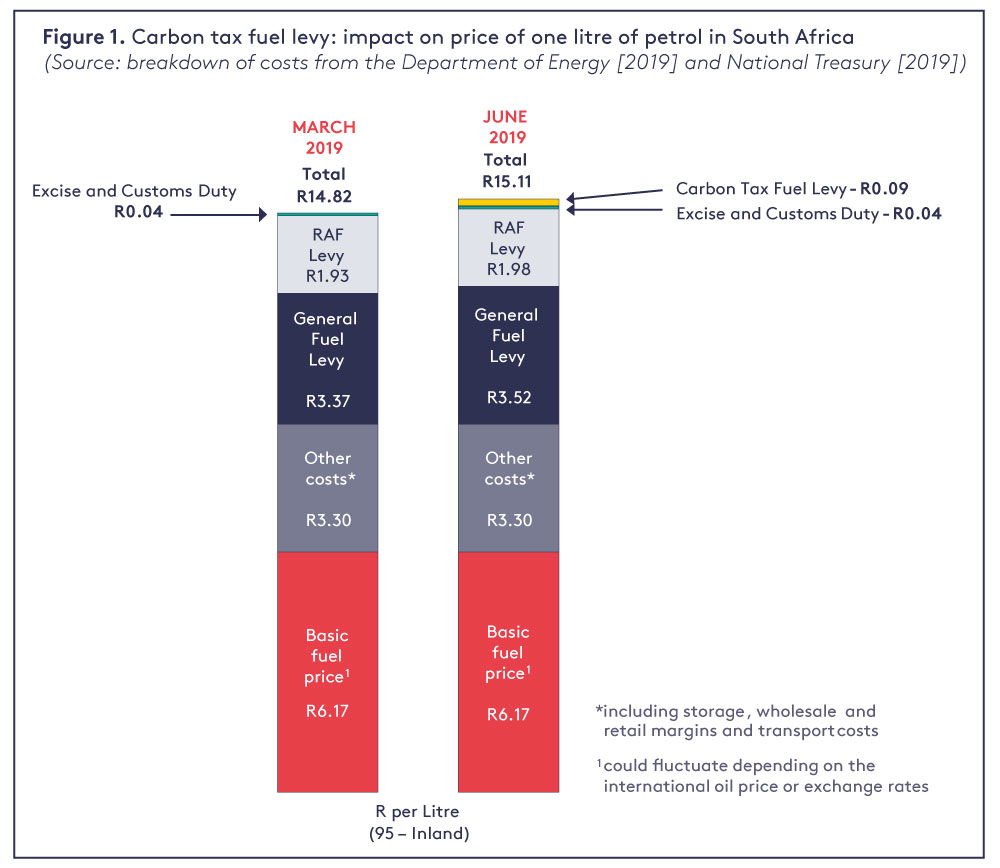

Based on the current proposals, the fuel levy will add an additional R0.09c for every litre of petrol and R0.010c for every litre of diesel – a breakdown of how this could affect a litre of petrol after June 2019 can be seen Figure 1.

Notes: The liquid fossil fuel price has long been subject to a general fuel levy, another that is ring-fenced for the Road Accident Fund (RAF), and a customs/excise levy. (The levies for petrol in 2019/2020 are R3.52, R1.98 and R0.04 per litre respectively. For diesel they are R3.37, R1.98 and R0.04 respectively.) Every year the general levy is increased to raise additional revenue for the National Treasury, or to support the RAF.

Changing consumer behaviour and reducing emissions will be very difficult without investment in transport alternatives

A key feature of any carbon price is to support the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by signalling the need for behaviour change. Indeed, the South African government states this objective in its Carbon Tax Bill. Through applying a carbon price to the fuel levy the intention is therefore to encourage consumers to switch to lower-carbon transport options (for example, switching from road to rail for goods transport, introducing lower carbon liquid fuels such as biofuels, encouraging investment in electric vehicles), or to alternative transport options (public transport or cycling).

But achieving behaviour change away from embedded modes of transport is challenging when commitments to infrastructure promote or engrain certain transport options, including the investment in road systems and certain city planning decisions. The sprawling nature of South Africa’s cities means they are not conducive to many types of alternative or public transport initiatives due to the large distances between them, and low housing densities. Vehicles are also major financial commitments for households and businesses, replaced relatively infrequently. Thus consumers, understandably, are not willing to make quick decisions in this area.

However, a few options could be further investigated to enable the shift, such as building more and improving existing railways, building charging networks that enable electric vehicles, developing emissions standards, or investment in bus networks. While the South African government’s climate strategy does recognise transport as a key area for action, there is currently little indication of concrete support for these lower carbon transport options, other than a vague reference to a desired shift from road to rail. In the 2019 budget the National Treasury did not announce any additional resources for this area. On alternative fuels, a biofuels blending regulatory framework was due to be published by March 2019, but there is no sign of it yet.

As such, South Africa does not yet offer sufficient alternatives to petrol and diesel vehicles – and consumers are much less likely to change their behaviour without them. Shifting away from fossil fuels in transport takes many years, and requires a diverse range of policies tackling different areas at the same time. This is illustrated by countries that have otherwise made strides in decarbonising large parts of their economies. In the UK, for example, emissions from the transport sector remain stubbornly flat, while in the United States, they are increasing.

The acceptability of a carbon price is essential to its effectiveness: South Africa must learn from France

Already we have seen calls for the levy to be reduced or even scrapped, from civil society actors and businesses. These have been fuelled by concerns related to the regressive nature of fuel levies in general, and to the additional cost imposition of the climate change levy.

Issues of equity and how these influence the overall acceptability of a policy are important considerations for implementation, as highlighted recently by the gilets jaunes protests in France. The proposed increase in the French equivalent of the climate change related fuel levy, the eco-tax, and its impact on fuel prices, drew fears that the poorest or most vulnerable in French society would bear the burden for the low carbon transition. While not solely to blame for fuel price rises, the eco-tax increase was announced without any clear indication or commitment to invest in alternatives, or support for the most vulnerable. The major social and political unrest that ensued, spiralling into widespread protests around social justice, ultimately led to the levy increase being paused, but not before major, potentially long lasting, embarrassment and damage was caused to President Macron and the French government.

South Africa should learn these lessons from France. Communication and consensus-building is critical before a tax of this sort is imposed. If the levy is implemented as announced, it could alienate or anger key constituencies that are needed in the transition to lower carbon growth and development.

Long-term climate policy should not be undermined by the need to raise revenue

Estimated to raise around R1.8 billion (US$125 million [1]) in revenue in the year 2019/20, the carbon tax fuel levy looks very much like a revenue-raising move from the South African government – and one being imposed upon already heavily burdened consumers.

This could be justified if there were sufficient low-carbon alternatives available for consumers or businesses, but we have seen that this is not the case. Without measures to shield them, the higher costs for fuel and transport could disproportionately affect the poorest and most vulnerable, as well as small and medium sized businesses.

Furthermore, alone the tax will not reduce greenhouse gas emissions significantly. While a carbon price is an important element of any climate change strategy, it must be complemented by a suite of policies and approaches to reduce emissions. Given the long periods needed for change to happen in the transport sector this is even more important.

For South Africa, this means more commitments are required to expand and improve public transport, support for alternative fuels, implement emissions standards for vehicle, or invest in low carbon transport options. These should provide households and businesses with long-term, viable alternatives to enable them to confidently switch and avoid paying the tax. Particular focus should be placed on offering support for lower socioeconomic groups or businesses.

If the levy is implemented as designed, and there is push-back or resentment, then the direct carbon tax applied to companies (where the majority of emissions occur) could be tarred with the same brush and ignite new opposition. This would have serious long-term consequences that could diminish the acceptability of both current and any future climate policies in South Africa.

For now, the imposition of the climate-related fuel levy in South Africa should be reviewed or delayed until the supporting policies are ready and able to be implemented.

[1] Assuming an exchange rate of US$1: R14.35 (as of 11/03/2019).

The views in this commentary are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Grantham Research Institute.