US and international climate politics in the forthcoming Biden era

Arnaud Koehl considers the extent of the role the new American administration can play in accelerating international action on climate and development.

As we move towards the culmination of an extraordinary year for the world, experts are starting to debate what the outcome of the US presidential election might mean for global climate action.

Changes likely to happen

Joe Biden’s manifesto pledged to tackle the climate emergency as one of its main goals, and his election records suggest his voting base is expecting him to deliver. Once sworn into office, he will make a wave of key signals on day one. The Democrat notably has promised to re-join the Paris Agreement and repeal a range of oil- and gas-friendly regulations. It is worth comparing this not with the status quo but with an alternative reality in which Donald Trump had likely deployed his isolationist, climate-sceptical agenda further. The new administration will also want to reengage the science community and reverse the exodus of scientists across governmental agencies.

Emerging appointments in the transition team – for example of Joseph Goffman, responsible for the Environmental Protection Agency transition, and Robert Bonnie, his counterpart in the Department for Agriculture (USDA) – seem to back up the promise to take the climate change issue seriously, although this remains to be confirmed after the new President’s inauguration. The nomination of John Kerry as special envoy on climate, to sit on the National Security Council, sends another strong signal. A further credibility boost could come from the fact that Vice-President-elect Kamala Harris is a former senator for California, a state with a history of enacting strict environmental regulations. Mrs Harris’ involvement in these matters has been low-key and even questioned, but includes a notable interest in environmental justice when she was district attorney for San Francisco. Further, her $10 trillion climate plan, designed for her presidential campaign, was more ambitious than Biden’s.

Following through on Mr Biden’s manifesto’s pledge for net-zero emissions by 2050 could induce a major shift for global climate action even if the US takes time to get on the right track. He might decide to promote the ‘We Are Still In’ coalition, a granular composite of mayors, governors and other state and private actors who unofficially represented the US at United Nations climate conferences during the Trump era. And bringing non-governmental actors on board would have the additional benefit of making sure that governmental policies are translated into action on the ground and last beyond this presidency.

At home, Mr Biden is expected to harvest several low-hanging fruits through executive action if he is partially hamstrung by a hostile Senate: it will be easy to reinstate the Obama era’s low-carbon regulations; he has vowed to create a White House National Climate Council; he could push for sectoral policies by restructuring the departments for transport, energy, interior, the treasury, and defence. Strengthening climate-related financial disclosure might also be on the list.

Towards a Green New Deal?

The continuation of the COVID-19 crisis will require a new stimulus. This could represent the best opportunity for Biden to sell his touted $2tn energy and climate action plan. While the country’s infrastructure is suffering from decades of underinvestment and risks remaining locked into carbon-intensive patterns while other countries across the world have initiated ambitious transitions, a rebranding of economic and climate efforts could be operated through the prism of jobs and national security.

Harvard Professor Naomi Oreskes recently cited California as an example of good practice here: “Climate change has been for such a long time a bad story […]. California proves that sensible environmental protection can go hand in hand with a growing, creative, striving, job-generating economy.”[i] This approach would also raise social acceptance to combine climate change mitigation and adaptation goals into integrated policies directly targeted at communities, reaping local co-benefits such as new green jobs, cleaner air, better health, enhanced productivity, and energy independence.

However, uncertainty looms large over the Biden administration’s ability to cement bipartisan deals, notably over a carbon tax. Constitutional changes are unlikely to happen because of the expected stalemate in Congress.

Besides, new legal risks are now posed by the new conservative majority in the Supreme Court. Polluting companies might be emboldened to bring more lawsuits against existing and new regulations. On the other hand, the enhanced dominance of a climate denialism position implies that the Court would renege on its role in related litigation, because it does not recognise the harm done. This position was evidenced during Justice Barrett’s Senate confirmation hearings. And although uncertainty surrounds the question of how Justice Gorsuch will rule, it seems relevant to observe that the Justice’s mother, Anne Gorsuch Burford, considerably weakened the Environmental Protection Agency’s clout during Ronald Reagan’s first mandate.

Legislation addressing other environmental issues, such as the Clean Air Act, could also be threatened. Still, a legislative branch willing to forge targeted deals could avoid court invalidation in the future.

What do these changes mean for global climate action?

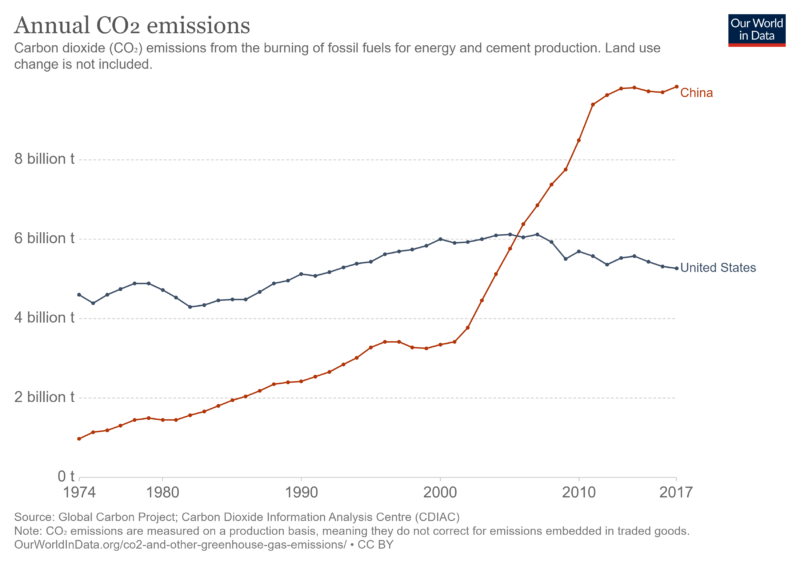

Will Joe Biden be able to exert a new global leadership on climate, and will it matter if he does or not? The dynamics of power have changed since China and the US, under the Obama administration, sealed an agreement that helped pave the way for the Paris Agreement. The world has also moved on through effective multilateralism in terms of climate policies. Meanwhile, the United States’ share of global emissions has decreased to being roughly half those of China in 2018 (see Figure 1), although the US still is the country with the highest cumulative CO2 emissions, with a share twice as high as China’s.

The US is still at the centre of geopolitics and its behaviour indirectly affects other countries, as it determines the strength of international pressure to meet commitments made in the past or to step up new efforts, and thus the effectiveness of the Paris Agreement. A shift of its leadership from obstacle to motor of climate action will be key to rebuilding trust among reluctant parties. The US could once again start to convince climate laggards such as Mexico, Brazil, Australia and major oil producers. How strong this domino effect can be will determine the overall strength of the transition to a global low-carbon economy.

In terms of partnerships, it is not yet clear whether Biden will turn to the European Union or China. As Laurence Tubiana, an architect of the Paris Agreement, recently said, “putting the green factor in the recovery resonates well across the Atlantic.”[ii] Mr Biden could seek an alliance of causes with both, as the EU is currently discussing the European Green New Deal, and China a potential green revamp of the Belt and Road infrastructure project. The alignments could lead to a more distributed leadership and be beneficial for other mutual interests, such as shared debt.

We are at a confluence where the road to recovery from COVID-19 constitutes a major chance to reshape climate action and a new US president-elect has vocally expressed his commitment in this area too. And next year will see the next major UN conference on climate change, COP26. The effectiveness of the Biden administration at home and abroad might determine whether COP26 will succeed in avoiding a lost decade for climate and development goals and provide the opportunity for a combined approach to tackle mitigation and adaptation. We shall soon know.

Arnaud Koehl has been working with the climate change legislation team at the Grantham Research Institute. He is based at Imperial College London. The views in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Grantham Research Institute.

[i] Speaking at a panel discussion, ‘International climate politics after the US presidential election’, hosted on 9 November 2020 by the Grantham Research Institute. The other speakers were Professor Anne-Marie Slaughter, Professor Naomi Oreskes, Professor Lord Stern, Laurence Tubiana, Professor Peter Trubowitz and Dr Robert Falkner. A recording of the discussion is available at www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/events/international-climate-politics-after-the-us-presidential-election/

[ii] Speaking at the same event.