Sustainable investment is good macroeconomics and fiscally prudent for the UK

In the global race for supremacy in 21st century markets, the UK must create expertise in building and deploying new energy technologies, and access the opportunities for stronger and more resilient growth that will bring. At the same time, it must reduce macroeconomic volatility and restore health to the public finances. This urgently requires political leadership, write Anna Valero and Dimitri Zenghelis.

The UK is now 15 years into a period of stagnant productivity and living standards, and the current growth outlook remains weak. At the same time, the world economy is facing profound technological change in a race to develop and supply the markets of the 21st century. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, sums previously unimaginable have been mobilised worldwide to fund sustainable sectors. The US Inflation Reduction and the CHIPS and Science Act have offered perhaps a trillion dollars in unlimited tax credits to leverage trillions more in private investment in clean sectors, while China has cornered the market for solar photovoltaic generation, electric vehicles and batteries. The European Union is vying to keep up through the Green New Deal and supporting measures.

The politics in the run-up to a general election are complex and, given the challenging fiscal context, much of the current debate has focused on Labour recently amending its pledges. But we believe that the economics are clear – there is no route to stronger, sustainable and more resilient growth in the UK without a significant increase in public and private sector investment. Not only is the former important in its own right: it is also required to enable the latter, in concert with complementary reforms to improve the business investment ecosystem, and as part of a much-needed new economic strategy for the country.

Our recent report sets out how 1 per cent of GDP (£26 billion in current prices) is the appropriate order of magnitude of increased public investment to produce a net zero infrastructure, support relevant innovation, and achieve broader sustainability and adaptation objectives against the backdrop of chronic underinvestment in the UK. We show how this should be phased in and also suggest how this could be financed (at least in part) through temporary and targeted borrowing.

Progress was being made in recent years, with public investment as a share of GDP rising. However, the tax giveaways announced in the Autumn Statement were ‘funded’ by future cuts to both investment and public services and new tax cuts are expected in at least one fiscal event before the general election – though this has been discouraged by the IMF and the Office for Budget Responsibility in the UK. The reality of the UK’s public service needs, an ageing population, increased defence spending, and net zero spending requirements imply that taxes will need to stay high relative to the past.

While the UK faces significant fiscal constraints and trade-offs need to be navigated, there are three broad requirements that need to be met for a bold investment strategy to succeed. Firstly, structural policies are necessary to boost productivity and raise living standards in the medium term. Secondly, a macroeconomic stabilisation framework is required to maintain low and stable inflation and preserve external trade and payments balance. Finally, the above should be combined with responsive and transparent institutional governance to secure credibility and leverage long-term private investment. Such a coherent set will require credible fiscal rules and policies to boost UK saving and investment.

Boosting long-run supply-side capacity

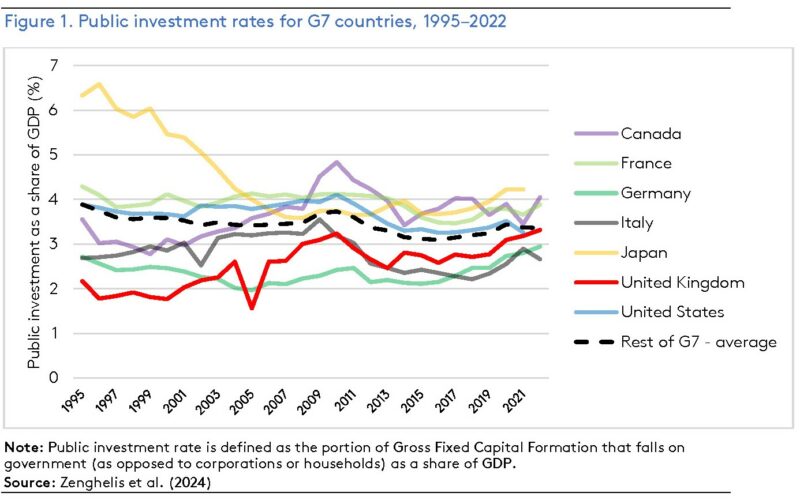

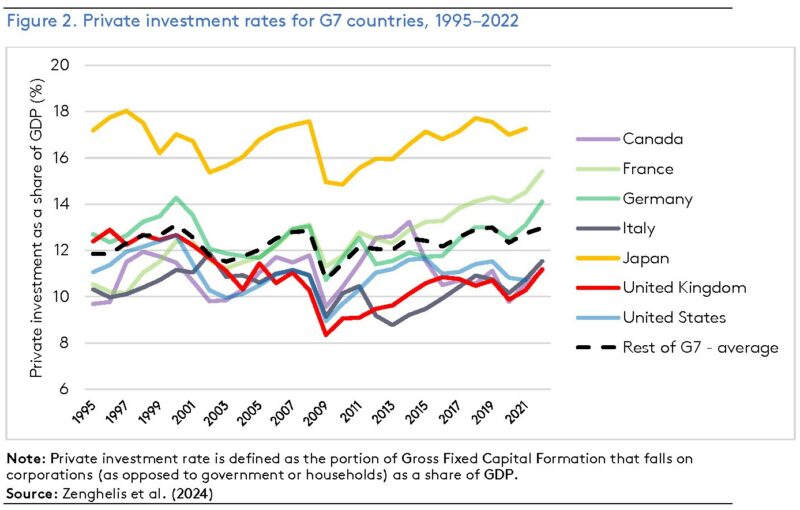

The UK ranks poorly compared with other advanced economies when it comes to both public and private sector investment as a share of GDP (see Figures 1 and 2 below), and this underlies its longstanding poor productivity performance. The problem of low public sector investment is also compounded by the volatility of that investment: both the quantity and quality must improve.

Looking forward, meeting net zero by 2050 requires significant additional investment this decade, with around a quarter of additional investment needing to come from the public sector. With real interest rates remaining historically low, and nominal rates falling back as we anticipated, the interest payments associated with substituting capital for wasteful future energy and resource flows are affordable. More broadly, it makes sense that investment should be future-proofed and aligned with the direction of global deployment of clean technologies, as well as AI and digital innovations. This would improve the resilience of the UK economy, and maximise the chance that UK firms can access some of the opportunities to serve growing domestic and international demand.

There are four ways to improve public debt sustainability as a proportion of GDP (see Table 1). They involve either a nominal restructuring, through debt default or higher inflation, both of which erode the real value of existing debt, or real restructuring, through tightening the fiscal screws or boosting growth in GDP. Of these, only the latter two ‘real’ options are sustainable. But the risks from further cuts in public investment in clean growth sectors are that this would strongly constrain GDP growth and worsen debt sustainability. By facilitating long-term resilient growth, investing in the world’s fastest growing business sectors is the only way to shore up future production and secure enduring public debt sustainability. If this has to be financed by borrowing, so be it: borrowing to increase future output and resilience is sound, in the way that borrowing to finance consumption is not.

Table 1. Options for reducing the public debt/GDP ratio

| NOMINAL | REAL | |

| Reduce numerator (debt) | Default, restructure or creditor ‘haircut’ – Cost to economic reputation – Increased future borrowing costs (default premium) | Austerity (cut spending/raise taxes) – Taxes up/public spending down – High cost to economy and society – Can be ineffective (because of denominator effect) |

| Increase denominator (GDP) | Inflation – Effective, but at economic cost – Hard to restore monetary credibility – Uneven distributional impact on society – Increased future borrowing costs (inflation premium) | Growing the economy and raising GDP – Effective if sustained – Positive impact on numerator by raising net public revenues – Positive for the economy and society |

As with all risk–opportunity-based strategies for assessing a structural transition, the precise magnitude of the change cannot be quantified. But the alternative of paring back or delaying vital investment at this critical time would likely prove to be economically and fiscally irresponsible, as well as environmentally damaging.

Achieving higher investment without an increase in UK saving would require increasing borrowing from abroad, implying a widening in the UK’s current account deficit. On one level, this does not matter. The higher debt would have its counterpart in increased productive assets in the UK: there would be no fall in national wealth. This is structural borrowing, in line with structural fiscal rules. So long as the investment is credible and does not spook markets (more on this below), such borrowing is fiscally sustainable in that it bolsters the size and resilience of future output and can be expected to pay for itself through higher future tax revenues and lower government spending. Together with supportive reforms to improve the business investment ecosystem, it can fund future saving and consumption, making these less volatile.

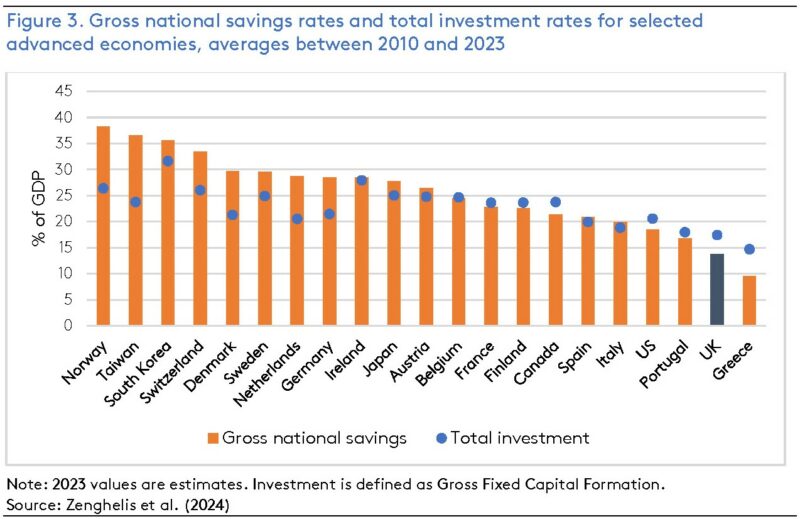

In practice, however, there are good reasons to favour at least some contribution from higher domestic saving. The UK’s current account deficit is persistently large, averaging 4 per cent of GDP over the past decade. And the UK’s savings rate is very low (the third lowest among OECD countries – Figure 3). This results in precarity in light of shocks, insufficient retirement savings for many, and implies that the returns to UK investments accrue to investors overseas.

Short-run macro stabilisation requirements

Focus must not be lost on maintaining macroeconomic balance. In the current broadly full-employment economy, additional investment would need to displace other spending, in order to prevent an increase in inflation and a further deterioration in the country’s trade and payments balance. There are three ways this can be brought about.

The first involves acknowledging that this is likely to result in the Bank of England raising rates to offset the increase in domestic spending and alleviate additional pressure on inflation. However, this might be expected to put upward pressure on sterling and widen the current account deficit, worsening external imbalances.

A preferable route would be through a voluntary shift by households to consume less and save more. This would relieve inflationary pressure and allow UK interest rates to stay lower and investment to rise. While worth striving for (and phasing up employer and employee contributions via pensions auto-enrolment is a plausible route), a secular rise in UK saving is not easy to bring about, at least in the near term.

This leads to the third route, reduced public borrowing (or lower public dissaving). This would require higher taxes or lowering current spending in order to maintain the structural fiscal position, limit pressures on inflation, and lessen borrowing demands from abroad. Given the current pressures on public services and future demands due to demographic change, it is clear that taxes must play a role here. The precise balance of taxes and borrowing would ideally be set according to sustainable fiscal rules (see below).

Credibility and market confidence

The UK’s experience at the time of the 2022 ‘mini budget’ illustrated that policymakers have reason to beware the bond market. But there is a clear distinction between a programme of unfunded tax cuts (to the order of £45 billion) and the phasing in of an investment programme that can plausibly boost the supply side of the economy. The Kwarteng-Truss tax cuts would have added to demand pressures in the short run (increasing inflationary pressures, pushing up interest rates, and widening the current account deficit) yet would have had a limited effect on growth in the long run. Bypassing the OBR, sacking key Treasury officials, and criticising Bank of England independence reinforced the loss of confidence in the policy package, and compounded the damage it produced.

Convincing markets of the credibility of a bold investment plan for the UK requires more than economic analysis: it would also require strong political leadership to convince markets that the Government understands, and takes seriously, the crucial difference between expenditure on investment and expenditure on consumption, and enshrines this in its fiscal rules.

The credibility of investment plans, as part of a broader growth plan, could also be boosted by a new statutory body focused on growth and productivity policies, including skills. Going to investors with a sound investment plan is a means to rebuild credibility, lower policy risk premiums and leverage private investment in the expectation of the future profitability of new markets.

Conclusion: short-term politics vs. long-term policy

While significant public investment is required to promote the deployment and development of sustainable technologies and set in train cost reductions, the private sector will take over with time. Once the clean digital economic machine is kick-started and running, and the UK attains a competitive edge, it will mostly take care of itself. There are reasons to be optimistic: the UK is an innovative economy, with key strengths in net zero products and services that can be built upon by embedding net zero into a broader growth strategy that builds on its strengths in services, life sciences and other areas of advanced manufacturing too. What does this all mean in practical terms?

- The UK should move towards a clear commitment for full tax funding of government consumption (a current budget balance rule) and earmarked borrowing for net investment, together with measures to encourage voluntary saving (like pension reform). This would suggest a level of structural borrowing of around 3% of GDP over the cycle, consistent with debt sustainability.

- The medium-term falling public debt to GDP rule should be dropped. It is at the core of the reason that much-needed investment tends to be cut every time the public finances are tight. Public debt is not a burden if it funds productive investment.[1] The value of the investment to the economy is independent of the past stock of debt. Notwithstanding data challenges, a better medium-term focus would be on improving public net worth, which accounts for the value of the public assets acquired, in order to assess the resilience of public debt.

- There must be more focus on improving the quality of investment, in terms of its economic (and broader societal) returns. And this requires better planning, careful auditing mechanisms and oversight.

- In order to raise the overall investment rate, and ensure that public sector investment catalyses substantial private sector investment in productive and sustainable UK assets, complementary measures to improve the business investment ecosystem are needed, in particular, addressing planning bottlenecks, pensions reforms, investing in skills and broader stability in growth and industrial policy.

- Honesty is required about how historically high (though not internationally high) taxes are likely to be needed for some time in the UK, together with a commitment to any increases in taxes being fair and part of a broader programme of tax reform, whereby distributional impacts need to be carefully considered.

These are difficult times, but paring back investment to pay for consumption is not what the UK needs at this moment, and will cost all of us in the long run. Without a structural boost to investment, the UK economy would likely continue stuck in a low investment, low saving, foreigner-dependent low growth trap. A shift from consumption to investment is needed, and this requires political leadership. There is a global race for supremacy in 21st century markets. The UK must create expertise in building and deploying new energy technologies, and access the opportunities for stronger and more resilient growth that will bring. It is not too late, but it is very late. It is time for the long view.

[1] Imagine a policymaker does not know the level of public debt but has to decide whether to borrow to invest in assets which generates strong returns. They are then told public debt is relatively high. This would not materially change their view on the appropriate fiscal stance, except in so far as higher debt impacts affordability by pushing up risk premiums on public borrowing rates, hence the importance of credibility.