Costs and benefits of the UK reaching net zero emissions by 2050: the evidence

As unbalanced, ill-informed articles on net zero continue to appear in the press from figures such as former Chancellor Lord Hammond, Bob Ward examines the evidence produced by our independent statutory bodies that carefully analyses the costs and benefits of acting on climate change in the UK and leads to a robust economic case for action.

The UK’s former Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hammond, has unwittingly highlighted the importance of politicians coming clean about both the costs and benefits of achieving the target of net zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050.

In a series of media interventions, Lord Hammond has claimed that politicians have attempted to hide the cost of reaching net zero, while himself failing to mention the huge financial savings and benefits that would also result.

The Telegraph has published Lord Hammond’s assertions on what it calls “the trillion pound cost of achieving net zero”: according to the former Chancellor, the paper’s article of 30 July says, successive Conservative prime ministers have been “systematically dishonest” with the public on this matter.

Then, in an article published in The Times on 1 August under the headline ‘Politicians have to come clean about full net zero costs’, Lord Hammond wrote:

“The UK in 2019 was the first country to commit itself to a legally binding net-zero target but five years on politicians of all stripes are still being coy about the economic implications of this massive undertaking.

“As chancellor at the time, it fell to me to report to parliament that the Treasury’s best estimate of the cost of meeting the 2050 net-zero commitment was between £1 trillion and £2 trillion – an estimate that was flatly rejected by No 10.”

He also wrote:

“So the net-zero commitment, which prioritises investment to change the nature of economic output (by decarbonising it), rather than expanding the quantity of economic output to deliver higher levels of private consumption and better public services, is a choice – but one I am not sure we have yet collectively and consciously made as a society. When we do, it has to be on the basis of transparent information about the costs as well as the obvious benefits.”

This is a rather curious article for several reasons. Firstly, there is no record of Lord Hammond reporting his figure of £1–2 trillion to Parliament. There are, however, media reports about a letter from Lord Hammond (or Mr Hammond as he was then) to the Prime Minister, Theresa May, which was leaked to the Financial Times.

The letter, which was published on 5 June 2019 on Twitter by the newspaper’s chief political correspondent, Jim Pickard, stated: “The Committee on Climate Change estimate that reaching net zero emissions by 2050 will cost c. £50 billion per annum by 2050. BEIS’s [the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy’s] own analysis find the costs to be 40% higher, at around £70bn per annum, but still within the annual cost envelope of 1–2% of GDP estimated by the Committee. On the basis of these estimates, the total cost of transitioning to a zero-carbon economy is likely to be well in excess of a trillion pounds.”

Secondly, Lord Hammond failed to make clear in either his Times article or his letter to the Prime Minister that his figure refers to the investment cost and did not take into account any savings or benefits of reaching net zero.

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) did, however, make this distinction clear in its advice to the Government in May 2019 about amending the emissions reduction target in the 2008 Climate Change Act from 80 per cent to 100 per cent – advice that Theresa May’s Government accepted. The CCC’s report on Net Zero – The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming includes Chapter 7 on ‘Costs and benefits of a net-zero target for the UK’, which states:

“The overall economic impact of cutting emissions and the costs of increasing ambition to net-zero are likely to be small globally and in the UK and could turn out to be positive. Accepting this cost is preferable to inaction given the range of risks from unchecked climate change globally and in the UK, both directly and indirectly.”

The report also stated: “Our central estimate for the resource costs of a more ambitious net-zero GHG [greenhouse gas] target in 2050 are in line with the expected cost accepted by Parliament when the current target was set – an annual cost of between 1–2% of GDP in 2050. If innovation exceeds expectations again this cost could be lower.”

Its central estimate was an annual resource cost of 1.3 per cent of GDP by 2050 but the CCC noted that it could be 0.9 per cent if fossil fuel prices are high or 1.8 per cent if fossil fuels are significantly cheaper than assumed. The report assumed that GDP in 2050 would be £3.9 trillion, so 1.3 per cent would be £50.7 billion.

The report defines resource costs as “estimated by adding up costs and cost savings from carbon abatement measures, and comparing them to costs in an alternative scenario (generally of a hypothetical world with no climate action or climate damages)”.

The report noted that actions to achieve the net zero target would create savings and benefits in addition to avoided climate change impacts; these are not factored in to the resource costs: “Achieving net-zero GHG emissions in the UK will result in significant benefits to human health from better air quality, less noise, more active travel and a shift to healthier diets. Changes to land use and farming practices that cut GHG emissions can also improve air quality and water quality and benefit biodiversity, resilience to climate change and bring recreational benefits. Benefits could partially or fully offset costs.” Such benefits are often referred to as ‘co-benefits’ of climate action.

The detailed calculations by the Committee on Climate Change informed the decision by Theresa May’s Government to introduce an amendment to the 2008 Climate Change Act to change the target for emissions reductions in 2050 from 80 per cent to 100 per cent. This amendment was passed by Parliament in June 2019.

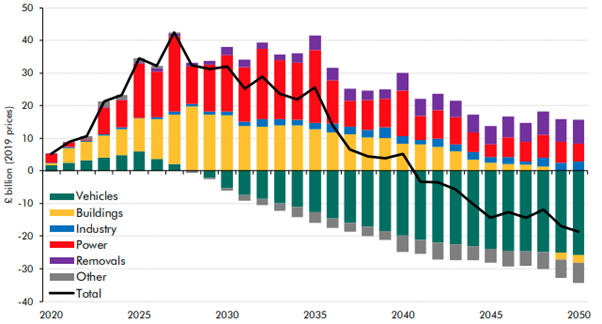

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) examined the Committee’s estimates in its July 2021 Fiscal risks report. It concluded: “In the balanced pathway, the CCC estimates the total net cost of abatement across all sectors of the economy between 2020 to 2050 at £321 billion – with £1,312 billion of investment costs mostly offset by £991 billion of net operating savings.”

It also noted: “From 2040 onwards, net operating savings are projected to outweigh investment costs. And by 2050, the CCC projects a £19 billion annual saving relative to its baseline emissions scenario.” If similar savings of the same size continued in the years beyond 2050, investment costs would be completely offset by 2070.

Figure 1. Net cost by sector of reaching net zero in the balanced pathway in the 2019 report by the Committee on Climate Change. Source: Fiscal risks report – July 2019, Office for Budget Responsibility

These calculations did not include the benefits from avoided climate change impacts or other co-benefits. The OBR report pointed out: “The costs of failing to get climate change under control would be much larger than those of bringing emissions down to net zero.”

Thus it appears that Lord Hammond has ignored the OBR’s findings that the net costs of net zero are likely to be far less than £1 trillion, and there will be net benefits once avoided climate change impacts and the co-benefits of net zero policies are taken into account.

The Climate Change Committee [as it is now called] provided updated estimates of the costs of reaching net zero emissions by 2050 in its advice to the Government about the Sixth Carbon Budget in December 2020. Its report The Sixth Carbon Budget: The UK’s path to Net Zero stated: “Overall, we find that the net costs of the transition (including upfront investment, ongoing running costs and costs of financing) will be less than 1% of GDP over the entirety of 2020–2050, lower than we concluded in our 2019 Net Zero report.”

The Committee modelled several different scenarios for resource costs and concluded: “Our analysis indicates that the annualised resource cost of reducing GHG emissions to Net Zero would rise towards 0.6% of GDP by the early 2030s, remain at approximately this level through the 2030s and early 2040s, before falling to approximately 0.5% by 2050. Our scenarios demonstrate the potential for slightly higher or lower costs, all around 1% of GDP or less.”

The Committee explained that these estimates were significantly lower than contained in its 2019 report: “Our Balanced Net Zero Pathway indicates that net annualised resource costs are on average £17 billion per year during the Sixth Carbon Budget period, and decrease to £12 billion per year by 2050. This is a significant reduction from our previous estimate of £50 billion in 2050 in our Net Zero report.”

Lord Hammond’s media interventions also fail to mention that neither the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (or its successor, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero) nor Her Majesty’s Treasury have ever published their own calculations of the cost of net zero. Indeed, the 2019 net zero report by the Climate Change Committee recommended that the Treasury “undertake a thorough review of the distribution of costs and benefits of meeting a net-zero target and the appropriate policy levers to achieve an efficient and fair transition”.

The Treasury duly completed a ‘Net Zero Review’, after Boris Johnson replaced Theresa May as Prime Minister and Lord Hammond had been succeeded as Chancellor by Rishi Sunak. The interim report of the review was published in December 2020. It noted: “The amount of investment required to reach net zero and the consequential impacts on operating costs are difficult to estimate. They are affected by a range of factors, including the precise path of the transition, changes in behaviour and the rate at which technology costs fall and efficiency gains are made, all of which are subject to significant uncertainty.”

It continued:

“As a result, any cost estimate is highly complex, speculative and should be considered as a scenario based on assumptions rather than a projection. Nevertheless, such estimates can provide a sense of the scale of the challenge. To support its report on net zero last year, the Climate Change Committee (CCC) estimated that the transition would have a net cost of £50 billion across all economic sectors in 2050. They have now updated this estimate to £16 billion. This includes assumptions about changes to behaviour, falls in technology costs and efficiency gains, all of which are highly uncertain. These costs are partial and do not include the costs of policy interventions or broader supporting investment such as skills development, nor do the CCC cost estimates capture the wider economic effects, the fiscal impacts, the nonfinancial costs to households and businesses, or all the co-benefits of decarbonisation.”

The final report of the review, published in October 2021, found that the net economic impact of reaching net zero is uncertain but likely to be relatively small: “The eventual net impact of the transition on output is highly uncertain and challenging to estimate. It will depend on the policies used to catalyse the change and technological progress that has not yet occurred. Efforts to quantify this impact can vary depending on factors such as the choice of model and counterfactual, however, most suggest the impact on output in 2050 is likely to be small relative to total growth over the period.”

But the review’s final conclusion was clear: “Overall, a successful and orderly transition for the economy could realise more benefits – improved resource efficiency for businesses, lower household costs, and wider health co-benefits – than an economy based on fossil fuel consumption.”

It is a great shame that Lord Hammond and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, both former Chancellors, seem so reluctant at the moment to acknowledge this robust economic case for action.