Budget shows the UK economy needs saving

Resolving the UK’s saving problem is a prerequisite to boosting long-term growth. If her economic strategy is to stay afloat, Chancellor Rachel Reeves must confront the taboos from the manifesto and make those tough choices she readily espouses, writes Dimitri Zenghelis.

Rachel Reeves’s welcome strategy to boost UK growth got off to a stuttering start. The fiscal watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), shaved 0.2% off its forecast for UK GDP by 2029 as a result of the October 2024 Budget measures. At the same time, UK borrowing costs rose after the Budget, with the 10-year gilt yield climbing to 4.44% by the following morning, while equities started to slide.

This potentially makes life hard for the Chancellor as she struggles to reform the public sector, boost investment and help fund a clean transition. But it testifies to an important macroeconomic truth that can no longer be skirted. With an economy running close to capacity, the UK cannot fund extra investment without boosting domestic saving. And the UK has a domestic saving problem.

The OBR’s concern, which the markets echoed, is easy to understand. The extra public investment necessary to raise UK productivity in the long run cannot be accommodated in the short run without a reduction in general consumption. Otherwise, the Bank of England will raise rates to choke off additional inflationary pressure, thereby ‘crowding out’ private investment.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies’ Paul Johnson missed the point when he urged Rachel Reeves to avoid “spooking the markets” because “we have to pay an enormous amount of interest on our debt”. The markets do not have a problem with generating debt to invest; the UK is a global outlier on underinvestment, not high taxes or public debt. The markets do, however, have a problem with the country consistently being unable to domestically source the resources.

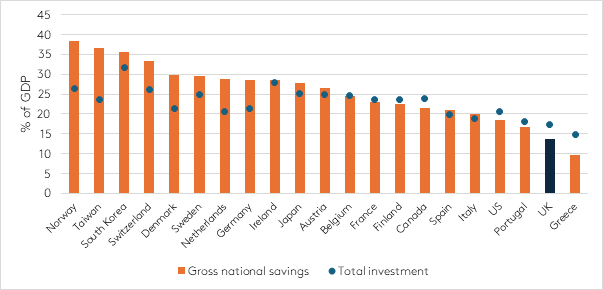

UK households, government and firms have not saved enough to fund the country’s relatively paltry investment record (see Figure 1). There is no shortage of cheap global saving, but the country has effectively relied on the ‘kindness of strangers’, reflected in a persistent current account disparity to fund investment. This results in vulnerability to shocks, insufficient retirement savings for many, and implies that the returns to UK investments accrue to investors overseas. UK interest rates also carry a higher premium above the global neutral rate.

Figure 1. Gross national savings rates and total investment rates for selected advanced economies, averages between 2010 and 2023

Note: 2023 values are estimates. Investment is defined as Gross Fixed Capital Formation. Source: IMF International Financial Statistics database, 2024

The Government’s decision to balance the current budget by fully funding day-to-day spending through taxes is helpful in building public saving, but it is not enough. In the longer term, structural policies like pension auto-enrolment designed to boost domestic saving, and pension reform to make better use of existing savings, create space for additional investment. The use of digitisation, AI and machine learning can help improve revenue collection and counter fraud, tax evasion and error.

Taxing ‘bads’ that we seek to discourage, like fossil fuels, pollution, unhealthy food, gambling and tobacco might help encourage saving. So might putting up the retirement age. But none of these will win plaudits in the popular press. Building more homes may also encourage saving, if they moderate the rise in house prices.

But in the short run, taxing consumption is the surest way to create space for UK investment. Any such tax increase need only be temporary, as the cyclically adjusted change in discretionary net public borrowing – a gauge of the net inflationary injection from public spending – starts to come down in the second half of the parliament. The problem is Reeves’s hands are tied by manifesto commitments, which rule out the use of key taxes such as income tax, value added tax (VAT), national insurance and corporation tax, which account for 75% of public revenues. Many of the impediments to transforming the economy will stem from this Labour Party original sin, designed to win the election.

VAT – a general tax on consumption – would be the most appropriate instrument. The UK still has more VAT exemptions than most countries. These distort spending choices and raise administrative costs. The poorest households, to which these exemptions are focused (and who consume a greater proportion of income than the rich), could be amply compensated for their loss through other payments, which leave them better off while still providing net tax revenue.

Instead, by relying on increases in capital gains tax and inheritance tax, Reeves rightly targets those with the broadest shoulders, but disincentivises saving and is unlikely to dent consumption. Her decision not to lift the freeze on fuel duty, even when oil prices are moderating, suggests she is not yet prepared to make decisions that are politically unpopular. After all, hands up who wants less consumption?

Reeves must now resolve the UK’s saving problem for her economic strategy to stay afloat, and this demands tough choices.