Why are household energy efficiency measures important for tackling climate change?

What does energy efficiency mean?

Energy efficiency means using less power to perform an action such as switching on a light or to provide a service such as heating water. For example, in the home this can be achieved by changing appliances such as fridges and boilers for more efficient versions, and switching to Light Emitting Diode (LED) and Compact Fluorescent Light (CFL) bulbs which require less electricity than traditional incandescent bulbs. There are also measures that can make heating or cooling a space more efficient through reducing the amount of energy that needs to be used. These include installing double glazing and insulating cavity walls and loft spaces.

What role can household energy efficiency play in tackling climate change?

Homes that use energy supplied from fossil fuels are responsible for significant emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). In the European Union, buildings consume 40% of overall energy and emit 36% of total CO2 emissions. In the UK emissions from households’ fossil fuel and electricity use are projected to rise by 11% by 2035 compared with 2015 levels. Therefore improving the efficiency of services and appliances that use energy from fossil fuels in the residential sector will reduce emissions. Other benefits include making energy more affordable, supply more secure and homes more comfortable.

Governments recognise the value of reducing households’ energy use. For example, the UK government views this to be a key part of meeting the emissions reduction target of the fifth carbon budget. Similarly, the United States’ Environmental Protection Agency has recognised that energy efficiency measures can help reduce CO2 emissions at a low cost, if employed on a sufficiently large scale.

What policies and incentives are there to make homes more energy efficient?

Around the world countries use a range of laws, policies, standards, subsidies and other incentives to encourage household energy efficiency. This partly reflects the fact that some measures have a high upfront cost, so support may be needed to encourage uptake.

Many measures are based in law. An example that applies to manufacturers of household electrical appliances is the European Union’s Energy Labelling directive, which requires many products to carry energy labels showing they have been designed to meet minimum energy efficiency standards. These labels and standards could result in an energy saving of around 175 million tonnes of oil equivalent by 2020. The EU’s main legislative instruments to improve the energy efficiency of European buildings are the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, recast in 2018, and the Energy Efficiency Directive. These include, for example, the target that by 2020 all new buildings must be ‘nearly zero-energy buildings’ (with very high energy performance and mostly supplied by renewables).

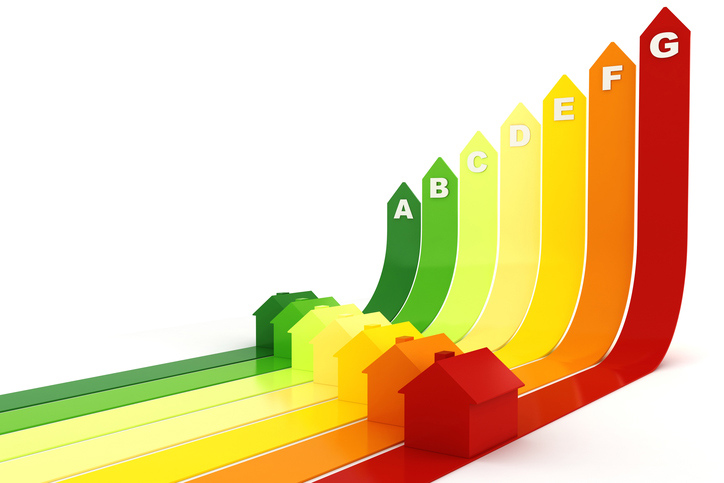

In some countries there are obligations on the construction sector. In the EU these are often implemented in order to comply with the above-mentioned directives. For example, the sector in France is required to apply energy efficiency measures to 500,000 existing homes a year by 2020 (this is called retrofitting). For sellers of homes in the EU there is a legal obligation to provide details of the property’s energy use and costs through Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs), which also provide recommendations of how to reduce use. Average EPC ratings have improved year on year for many years in the UK.

Developing and transitioning economies including China, Egypt, India and Mexico, are also increasingly developing building codes for new-build homes and working on enforcing compliance. China has achieved a high compliance rate, for example, and Mexico City, which developed its Sustainable Buildings Certification Programme in partnership with the local construction and building industry, has achieved significant electricity reductions in participating buildings.

Some countries have programmes of voluntary measures. For instance, the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s ‘Energy Star’ includes an independently certified label for energy-efficient goods, a rating for homes that are 15–30% more efficient than ‘typical’ new homes, and a retrofitting scheme to make existing homes more energy efficient.

Among the many examples of financial assistance provided to households, Germany’s KfW, a government-owned development bank, offers loans at a very low interest rate to install energy efficiency measures. The UK’s Energy Company Obligation (ECO) provides financial assistance to households receiving certain state benefits or those on a low income. Energy efficiency upgrades under the ECO scheme and the UK government’s flagship ‘Green Deal’ scheme, which also provides loans, had occurred in around 1.8 million properties to the end of October 2017.

What impact have energy efficiency policies already had?

The EU reports that new buildings (including but not restricted to homes) today consume half the energy they did in the 1980s. The average UK household reportedly used around 30% less energy in 2017 than in 1970, largely due to energy efficiency policies. Government policies such as building regulations and obligations on energy suppliers to install energy efficiency measures in people’s homes have been recognised as a significant driver of the improvement of the average energy performance of buildings in England and Wales. However, the Committee on Climate Change has criticised the ‘low take-up of measures, less than full implementation of policies [and] poor enforcement of standards’.

In Denmark, building codes are among the most ambitious and strict for comparable countries in the EU and resulted in households’ energy consumption decreasing by 6.2% from 2000 to 2013 (an average of -0.5% per year). The US Environmental Protection Agency says that its Energy Star programme, including household energy efficiency measures, prevented 2.8 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions from 1992–2015. Significant variations exist in the returns to energy efficiency, however; for example, households in lower income groups experience lesser energy savings after installing measures than better-off households.

What can be done to make energy efficiency measures in households more effective?

Overall, improving the energy efficiency of buildings offers a large potential to reduce emissions and reduce costs. However, this potential remains still largely untapped, due particularly to the long payback periods and high upfront costs. Generally, in developing and transitioning economies, where construction is happening rapidly and at significant scale, the priority is to ensure that new housing adheres to optimal standards in order to ensure energy-efficient consumption well into the future. In the developed world, retrofits are the main challenge given that approximately 60% of the current building stock will still be in use in 2050 in the EU, Russia and the US. A mix of financial incentives and regulation is needed to increase the uptake of energy efficiency measures, together with clear targets for renovation rates of existing buildings.