Asia’s steel expansion is creating carbon lock-in

In several South and Southeast Asian nations new steel production that relies on traditional blast furnace technology rather than lower-carbon alternatives risks locking in high-carbon industrial processes and severely undermining global efforts to reach net zero for several decades to come, write Sangeeth Selvaraju, Mateus Getlinger Santomauro and Guillaume Bastos Martin.

India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam are among a number of countries in South and Southeast Asia that are planning to expand their steel production capacity at a scale that dwarfs planned expansions in Europe and the US. Problematically, most of these planned expansions will employ old-fashioned, carbon-intensive methods of manufacturing steel. With the lives of new steel plants spanning into the decades, Asian steel producers risk locking in high-carbon industrial processes which will see their emissions in this hard-to-abate sector rise rather than fall.

Steel giants in South and Southeast Asia are planning to almost triple their capacity, with India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam charting similar trajectories. Together, these four countries plan to add 466 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of new steel capacity, 17 times more than the planned capacities of Germany, Japan and the US combined. Out of this massive expansion, only 60 mtpa (12.8%) will use lower-carbon-intensity electric arc furnace (EAF) technology. The remainder of the expansion will likely lock in decades of high-carbon emissions through traditional blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) technology.

Domestic demand is driving growth

This growth is mostly driven by projected domestic demand. As a result, emerging carbon-related trade restrictions such as Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms (CBAMs) imposed by the EU, the UK and other regions are unlikely to deter high-carbon-capacity expansions. These four emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) in South and Southeast Asia are expanding their basic materials industries to satisfy their growing economies. However, their choice of conventional high-carbon technologies with asset lives of 40–50 years will lock in emissions for the coming decades. While there are international initiatives that support collaboration and partnerships between developed and developing countries in relation to the technology and finance needed to enable lower-carbon-capacity expansion, they seem to be having a limited impact on these expansions.

Lower-carbon pathways are available

Steel production accounts for approximately 7–9% of global greenhouse gas emissions; decarbonising the steel industry is therefore crucial for reducing industrial greenhouse gases. EAFs powered by renewable energy can reduce emissions by up to 75% compared with traditional blast furnaces, and hydrogen-based direct reduced iron (DRI) routes offer the prospect of near-zero emissions steel. EAFs powered with green electricity further reduce carbon emissions by recycling scrap steel, making the latter an important component material in the operationalisation of EAFs. Using scrap steel instead of iron ore reduces carbon dioxide emissions by 58%. The availability of scrap steel is therefore a vital factor in technology choice. Unlike in developed markets, which industrialised earlier, most EMDEs have limited scrap availability. These lower-carbon pathways entail higher upfront costs and infrastructure requirements, but they also ensure a less carbon-intensive framework for the sector.

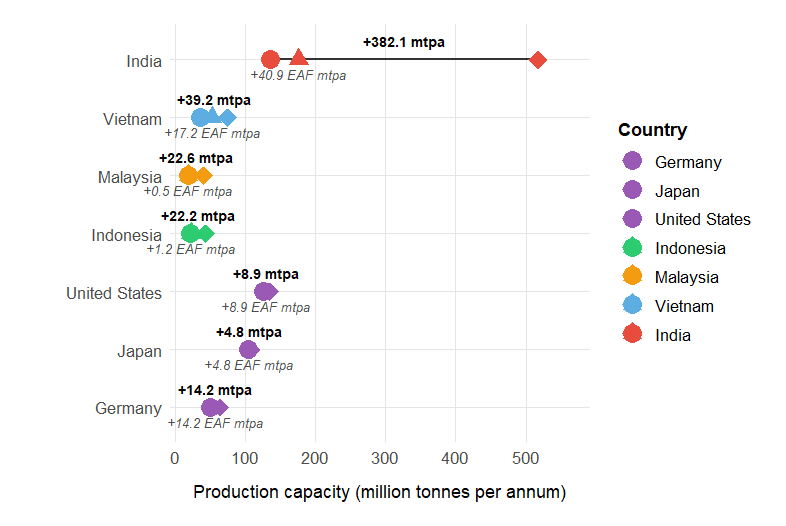

The scale at which the steel expansion is occurring is staggering (see Figure 1). India alone is adding 382 mtpa of capacity up until 2047, more than the current combined capacity of the other three countries studied (209 mtpa), which represents a 223% growth rate and is 7.8 times the size of Germany’s entire current steel capacity.

Figure 1. The EAF expansion story

Notes: Current vs expansion targets for steel production capacity in mtpa. Circles = current capacity; diamonds = target capacity; triangles = EAF (green) expansion. The GEM database was used to track BOFs vs EAFs when it says the share of expansion is in EAF technology. Expansion targets represent all capacity tracked by the GEM database (under construction or announced); therefore, exact timelines may differ for each of the countries.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Global Energy Monitor

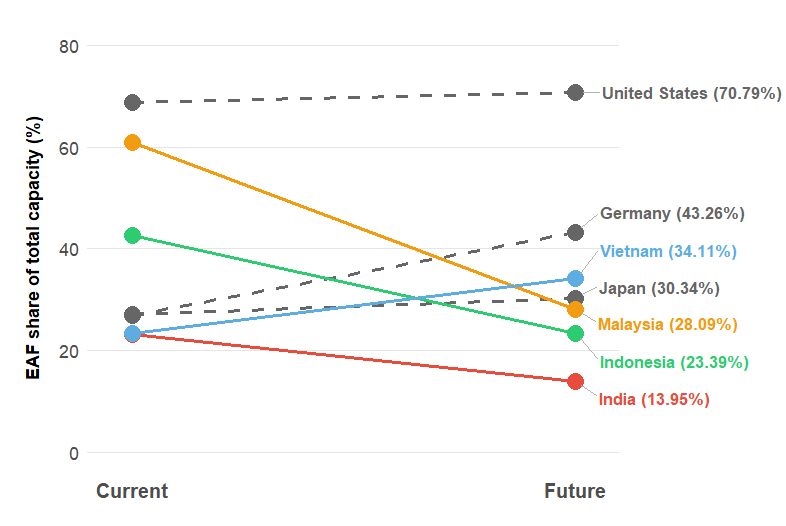

South and Southeast Asian countries currently maintain relatively clean steel production profiles; however, their expansion plans favour carbon-intensive furnaces. Of Indonesia’s current capacity, 42.5% is through EAFs, yet only 5.4% of its expansion plans employ the same technology. Similarly, 60.8% of Malaysia’s current capacity is through EAFs, the highest share in the region, but only 2.2% of its expansion maintains its low-carbon competitive advantage. Except for Vietnam, which is a large importer of scrap steel, the countries investigated are significantly reducing their EAF share of total steel capacity (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. EAF technology is losing its share of the steel production matrix

Notes: Current vs expansion targets of EAF share of total capacity (%). ‘Future’ represents all capacity tracked by the GEM database (under construction or announced); therefore, exact timelines might differ for each of the countries.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the Global Energy Monitor

Why are countries and firms choosing the carbon-intensive path?

Capital cost pressures play a big role in these investments. Although BOF and EAF plants typically require similar amounts of upfront capital (about US$300–400 per tonne of capacity), hydrogen-based DRI could cost up to US$700–900 per tonne. Hydrogen-based DRI is also more expensive to implement. In the absence of effective carbon pricing in these countries, these additional costs for using greener technology might prove challenging in the long run.

Missing price signals compound this problem. While the EU’s CBAM is now a reality, it is not affecting the capacity expansion as its complexity, phase-in timeline and uncertainty about how it will be applied mean it is not being considered in investment decision-making.

Infrastructure gaps also create additional barriers. EAF production requires a reliable renewable electricity supply, typically around 500 kWh per tonne of steel, and access to scrap steel feedstock. Most of the developing economies in the figures above are still dominated by fossil fuel generation and they do not have mature scrap collection and processing infrastructure.

Lessons from developed economies

Germany is retiring BOF capacity while exclusively building EAFs, driven by government state aid and carbon contracts for difference, guaranteeing steel producers a price for the green premium on their production. The country’s Climate and Transformation Fund has allocated about €4 billion specifically for industrial decarbonisation, making capital available on terms that reflect the social value of emissions reductions rather than purely private returns.

Our recent report finds that Europe, Japan and other developed markets have committed more than €14 billion in direct capital expenditure support for low-carbon steel projects. The report states that this is only one among many forms of state subsidy that have been made available for steel decarbonisation. In addition, they are supporting scrap collection and have begun to use language around monitoring and banning the export of scrap steel, sometimes termed ‘scrap leakage’ in policy documents.

However, with developed countries adding just 28 mtpa of capacity compared with 466 mtpa for just the four developing countries discussed above, their actions have a limited impact. The climate mathematics only work if the much larger new expansion is also the greener one.

A narrow window exists for redirection

Immediate priorities should focus on making green steel financially competitive. Development finance institutions could play an important role in conditioning steel project financing on carbon intensity thresholds. This would not prohibit BOFs entirely but would require developers to demonstrate that lower-carbon alternatives are genuinely not feasible before receiving concessional financing. Such conditional financing could also be tied to the commitments made by major steelmakers to net zero.

Financial support through government carbon contracts, like in the German model, could also help lower market risk when making the jump to greener steel. This would give large steel producers a bigger incentive to adopt new technologies and provide a market for the necessary energy infrastructure.

Asia’s steel capacity expansion needs intervention to avoid significant carbon lock-in

Investment decisions being made today in India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam will shape global emissions trajectories for the next half-century. These four countries are building 466 mtpa of new steel capacity, largely sustained by India. Yet only around 13% of this massive build-out uses lower-carbon technology, even as developed economies transition entirely to EAFs. The world’s largest steel expansion is also its most carbon-intensive, precisely when climate constraints are tightening and major export markets like the EU and UK are implementing carbon border adjustments.

Governments and multilateral organisations can play a key role in ensuring green steel production options are financially viable and achievable in these economies. Development finance institutions can make carbon intensity thresholds a condition for project financing and governments can implement carbon contracts for difference that make green steel financially viable.

Without intervention, this capacity expansion risks becoming another major climate challenge. The question remains: can emerging markets and developing economies manage to build steel capacity in ways that remain economically viable in a carbon-constrained world?

A version of this commentary was first published by Outlook Business.