As South Africa’s carbon tax is delayed again what is the story so far?

Today the South African finance minister, Tito Mboweni, postponed the implementation of South Africa’s carbon tax for six months in his first Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement given on behalf of the South African Treasury.

The implementation date had previously been set as 1 January 2019 (in the 2018 National Budget in February). While there is still a commitment to implementation in 2019, the new date is now 1 June.

Delays to introducing South Africa’s promised carbon tax are not new. Mr Mboweni is the country’s seventh finance minister since the tax was first proposed in 2010, and it is four years since the original intended implementation date of 2015.

A nine-year discussion about carbon pricing and carbon tax

The carbon tax is the centrepiece of South Africa’s climate change mitigation response strategy, which forms the basis for the country’s Nationally Determined Contribution to the Paris Agreement.

A carbon price was first mooted in 2010 in a National Treasury discussion paper. Other documents and announcements followed, including the National Development Plan to 2030 (NDP) in 2012, which identified a carbon tax as the policy instrument of choice.

The National Treasury was set the task of designing the tax. In 2013, it proposed an upstream tax on fossil fuel inputs for firms in the energy, industry and transport sectors, while initially exempting agriculture and waste. The design included a number of features to increase its acceptability and to limit the initial impact on the South African economy. The proposed tax rate of R120 (today equivalent to US$10) per tonne of carbon-dioxide-equivalent (tCO2e) was intended to increase by 10% a year until 2020 (phase 1), when it would then be reviewed.

Among the mechanisms proposed to make the tax more acceptable were an exemption for 60% of emissions by firms in all the covered sectors, additional tax-free emissions allocations for trade-exposed, energy-intensive sectors or those that had invested in efficiency measures, and allowing firms to utilise offsets to reduce a portion of their tax liabilities. An upper limit was set allowing up to 90% of emissions by any firm to be exempt, so the effective tax rate would range somewhere between R6 and R42 per tCO2e.

A start date was also set: 1 January 2015.

What followed was a series of delays, with implementation postponed indefinitely in the 2016 National Budget statement. Then, towards the end of 2017, the release of a Draft Carbon Tax Bill unexpectedly moved it back into the public eye. Agreement on implementation finally came in early 2018 with the announcement that the draft bill had been formally adopted by the Cabinet of South Africa to be introduced in January 2019. The 2018 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement has now postponed this once again.

Little has changed – but significantly, the annual escalation rate has been weakened

The delays to implementation are ostensibly to allow further consultation and improvements to the tax’s design, and support alignment with other climate-related policies. The description of the carbon tax in the current bill contains more detail and clarity, but all of the main components, including the headline tax rate, the sectors covered, the allocation of tax-free emissions and the use of carbon offsets, are the same as first proposed in 2013.

However, one notable change stands out: a weakening of the fixed 10% annual escalation rate. Now designed to be flexible, the annual rate is equal to the previous year’s consumer price inflation (CPI) rate plus two percentage points up to 2022; after 2022 only the rate of CPI applies. For example, if inflation were to be maintained annually at the upper band of the current inflation target of the South African Reserve Bank (6%), this would mean the tax is increased by 8% a year to 2022, and then 6% per year to 2030.

The escalation rate is an important element of any carbon tax and is key to its potential long-term effectiveness. It is important that the carbon tax’s escalation rate is sufficient to send the right signals to meet intended emissions reductions. A plan to increase the tax rate over time sends clear signals to the covered firms about future costs, enabling them to plan long-term investments accordingly. Linking the escalation to inflation potentially weakens the connection to the pathway for emissions reductions. It is difficult to predict what the annual inflation rate will be five or 10 years into the future. This could undermine the effectiveness of the tax as it will make future rates uncertain – sending mixed signals and making forward-planning for both those covered by the tax and investors more difficult. It will also make it difficult to assess whether the carbon tax will deviate from the rate required to achieve the desired pathway for emissions reductions.

The rate of tax and the escalation are too low for South Africa to meet its Paris pledge

It is challenging to estimate the level at which the carbon tax should be set to drive emissions reductions, but the the Report of the High Level Commission on Carbon Prices, chaired by Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern, suggested a range between US$40 and US$80 per tCO2e by 2020, increasing each year to reach between US$50 and US$100 per tCO2e by 2030. Tax rates at these levels would be consistent with emissions reductions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement, if they are supported by other climate-related policies.

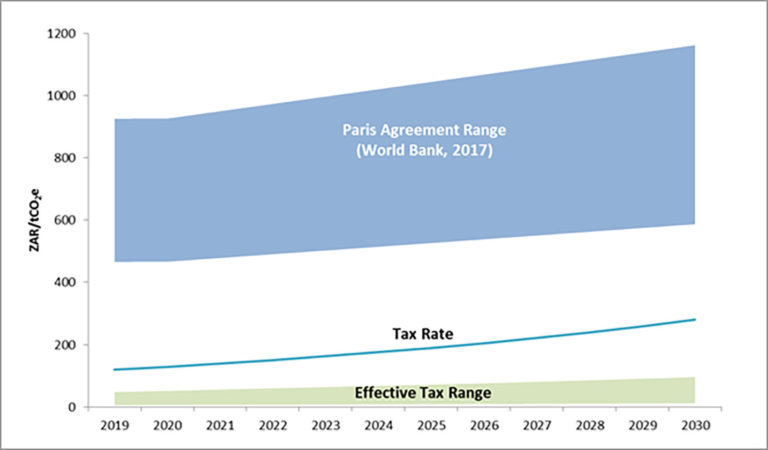

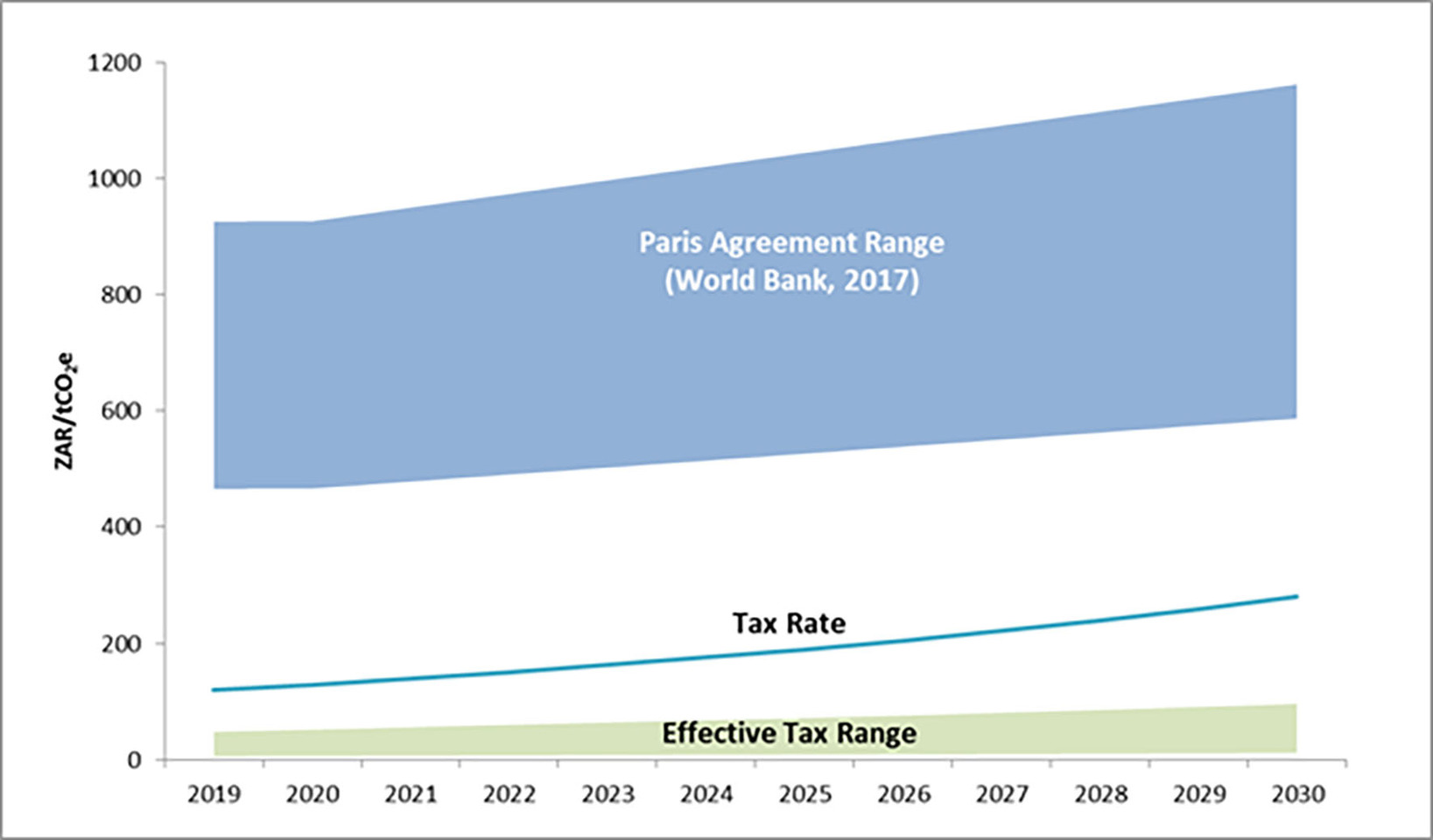

At an average exchange rate (i.e. US$1.00 = R11.50), the Stern-Stiglitz findings would correspond to a range of R460 to R920 in 2020 rising to R575 to R1,150 per tCO2e in 2030. South Africa’s proposed tax rate is currently R120, and the gap with the Stern-Stiglitz findings would be expected to persist even if the rate doubles to around R280 in 2030 with the proposed escalation rate (assuming inflation is kept at the top of the inflation target of 6%).

No company in South Africa will pay the full tax rate due to the tax-free allowances for emissions that are proposed. When these are taken into account the gap between the Stern-Stiglitz levels and South Africa’s carbon price is even bigger (see Figure 1). For individual firms, effective tax rates could be between R6 and R42 per tCO2e in 2020 (US$0.50–US$3.60), and from R42 to R84 in 2030 (US$3.60–US$7.20).

Figure 1: Comparison of the planned South African carbon tax levels to recommended levels (source: author)

Long-term signals from climate policies are important for investors – and currently South Africa’s signals are too weak

The South Africa Mitigation Potential Analysis (MPA), completed in 2014, showed that around 25% of greenhouse gas emissions will be covered by a carbon price signal in 2030 if the tax is implemented as planned. This would leave 75% of emissions still to be covered by mitigation action.

What is more, without a strong and clear price signal, and the appropriate range of supporting policies, South Africa’s policy environment could be too weak to attract a sufficient scale of investments to finance these mitigation actions. This could undermine an effective low-carbon transition.

South Africa’s climate change response has already been labelled as “highly insufficient” by Climate Action Tracker in relation to the Paris Agreement. The current design of the carbon tax is unlikely to change this significantly. All countries need to ramp up their action to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal of holding the rise in global mean temperature to “well below 2oC”. South Africa ratified the Paris Agreement on 1 November 2016, and should be heading in a direction that is consistent with its goals.

Escalation of the tax rate must be reinforced as the carbon tax bill nears implementation

It has taken nearly nine years for the carbon tax to arrive at this pre-implementation stage. Indeed, it could have been easy for firms and the Treasury to forget about the tax. The further postponement is regrettable, and should be avoided in future. If there are any changes introduced to the design of the tax during this delay these should be to strengthen the signal for emissions reductions and ramp up South Africa’s climate change action, not weaken it.

At a minimum, either the tax rate should be set to rise to levels that converge with the Stern-Stiglitz recommendations from 2020, or an explicit commitment should be included in the bill to reach these levels by 2030.

It is an inherent characteristic of a carbon tax is that it is not possible to predict with any certainty what emissions reduction will result from a particular rate. Therefore the plans for the carbon tax should also include a commitment to carry out reviews at regular intervals, set in advance and outlined in the policy, with the expectation that the tax might be adjusted to ensure the rate of emissions reductions within sectors covered by the carbon tax is consistent with the country’s overall mitigation strategy. This would allow firms to anticipate potential changes and limit uncertainty.

The next 10 years will determine whether the world will be able to meet the goals set out in the Paris Agreement, and implementing the carbon tax will be an essential part of South Africa’s contribution. The carbon tax should help South Africa to meet its mitigation goals and to unlock the opportunities of a low-carbon economy. It is now imperative that clear direction is provided so that investors, companies and individuals can plan accordingly.

Patrick Curran is a policy analyst and research advisor to Professor Stern at the Grantham Research Institute. The views in this commentary are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Grantham Research Institute.