National fishing industries rely on other countries to the tune of £8 billion a year

New study maps how ocean currents connect the world’s fisheries

A new study published in the journal Science finds that the world’s marine fisheries form a single network, with over $10 billion (£8 billion) worth of fish each year being caught in a country other than the one in which it was spawned.

While fisheries are traditionally managed at the national level, the study reveals the degree to which each country’s fishing economy relies on the health of its neighbours’ spawning grounds, highlighting the need for greater international cooperation.

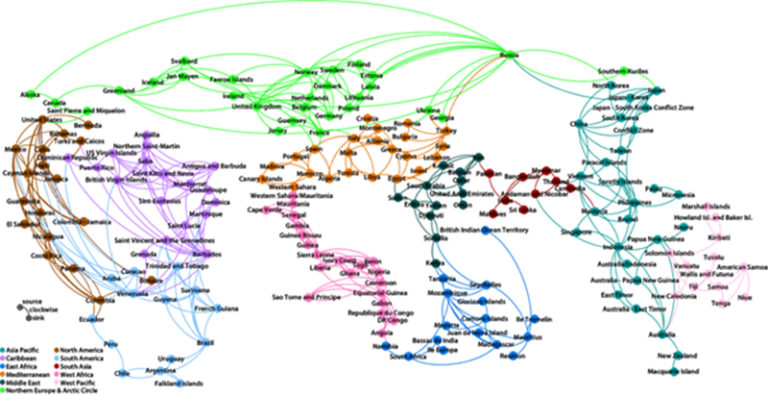

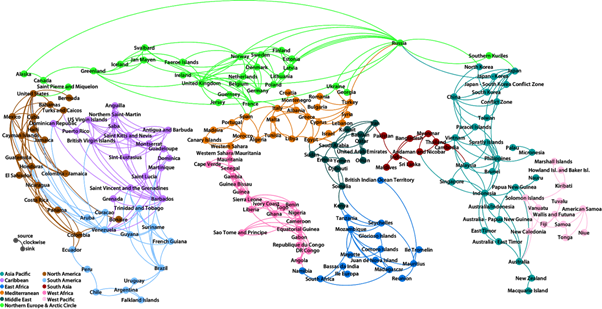

Led by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, the London School of Economics, and the University of Delaware, the study used a particle tracking computer simulation to map the flow of fish larvae across national boundaries. It is the first to estimate the extent of larval transport globally, putting fishery management in a new perspective by identifying hotspots of regional interdependence where cooperative management is needed most.

“Now we have a map of how the world’s fisheries are interconnected, and where international cooperation is needed most urgently to conserve a natural resource that hundreds of millions of people rely on,” said co-author Kimberly Oremus, assistant professor at the University of Delaware’s School of Marine Science and Policy.

The vast majority of the world’s wild-caught marine fish, an estimated 90%, are caught within 200 miles of shore, within national jurisdictions. Yet even these fish can be carried far from their spawning grounds by currents in their larval stage, before they are able to swim. This means that while countries have hard boundaries on their national fisheries, the ocean is made up of highly interconnected networks where most countries depend on their neighbours to properly manage their own fisheries. Understanding the nature of this network is an important step toward more effective fishery management, and is essential for countries whose economies and food security are reliant on fish born elsewhere.

The research shows that ocean regions are connected to each other in what’s known as a “small world network”, meaning that threats in one part of the world could result in a cascade of stresses, affecting one region after another.

“We are all dependent on the oceans,” said co-author James Rising, a researcher in the Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics. “When fisheries are mismanaged or breeding grounds are not protected, it could affect food security half a world away.”

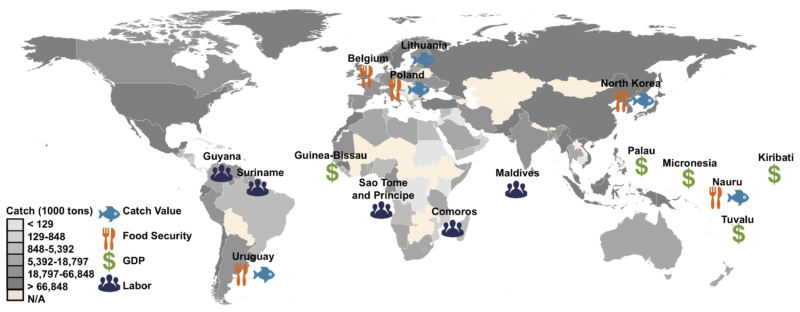

“By modelling dispersal by species, we could connect this ecosystem service to the value of catch, marine fishing jobs, food security and gross domestic product,” Oremus added. “This allowed us to talk about how vulnerable a nation is to the management of fisheries in neighbouring countries.”

They found that the tropics are especially vulnerable to this larval movement—particularly when it comes to food security and jobs.

The authors are experts in the fields of oceanography, fish biology, and economics.

“Data from a wide range of scientific fields needed to come together to make this study possible,” said lead author Nandini Ramesh, a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at the University of California, Berkeley. “We needed to look at patterns of fish spawning, the life cycles of different species, ocean currents, and how these vary with the seasons in order to begin to understand this system.” The study combined data from satellites, ocean moorings, ecological field observations, and marine catch records, to build a computer model of how eggs and larvae of over 700 species of fish all over the world are transported by ocean currents.

A surprising finding of the study was how interconnected national fisheries are, across the globe. “This is something of a double-edged sword,” explained lead author Ramesh, “On one hand, it implies that mismanagement of a fishery can have negative effects that easily propagate to other countries; on the other hand, it implies that multiple countries can benefit by targeting conservation and/or management efforts in just a few regions.”

“Our hope is that this study will be a stepping stone for policy makers to study their own regions more closely to determine their interdependencies,” said Ramesh. “This is an important first step. This is not something people have examined before at this scale.”

For more information about this media release please contact Kieran Lowe on +44 (0) 20 7107 5442 or k.lowe@lse.ac.uk

To interview one of the authors:

Nandini Ramesh, postdoctoral scholar, University of California, Berkeley, nandiniramesh@berkeley.edu, 914-356-1824

James Rising, assistant professorial research fellow, London School of Economics, j.a.rising@lse.ac.uk, +44 (0)2071075027

Kimberly Oremus, assistant professor of marine policy, University of Delaware, oremus@udel.edu, 302-831-1503

More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found online at the Science press package at https://www.eurekalert.org/jrnls/sci. You may also request a copy of the paper by contacting the AAAS Office of Public Programs at 202-326-6440 or scipak@aaas.org.