How much will it cost to cut global greenhouse gas emissions?

Assessing the cost of climate change mitigation

Economists continue to model the scale of investment required to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate the risks of climate change, and the ways in which this can be done. The Paris Agreement on climate change set a target of staying within 2°C of warming, which requires swift and decisive action to cut emissions. The question is: how much will it cost?

In its review of the latest scientific evidence, Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that putting in place mitigation measures to reduce emissions enough to limit probable warming to 2°C entail losses to global GDP of between 1.3% and 2.7% in 2050. In following action to limit probable warming to 1.5°C, losses are between 2.6% and 4.2%. However, cutting emissions in this way would also entail benefits, which are likely to outweigh global mitigation costs over the 21st century.

The overall costs of mitigation look quite small when compared with the strong underlying growth that the global economy is likely to experience. Regardless of the level of mitigation action, global GDP is projected to at least double over 2020–2050. But also, investment in green industries and infrastructure as part of climate change mitigation can boost GDP.

Cost estimates ultimately depend on the assumptions made about the availability and costs of different emission abatement technologies, the scale and pace of emission cuts required and the timescales considered in the models. Innovation changes the structure of the economy. This means the parameters of any model, including the costs of technology or tastes and preferences, that are factored into any assessment would need to correspondingly change. Cost-benefit analyses based on a unique ‘equilibrium model’ with fixed parameters (which most current modelling exercises are still based on) will therefore tell us little about likely future costs (see Section 5.5 of the UK Government’s Green Book 2022). Because they are unable by design to account for innovation dynamics, they will tend to overstate the costs of a low carbon transition and understate the benefits. The focus should therefore shift onto the drivers of innovation and the potential for innovation to sharply lower costs.

As the economist Nicholas Stern wrote in 2018, “The study of public economics has not, in its foundations, ignored processes of change but I think it is fair to say that they have been either on the margins or much less central than they should have been.” Put simply, the future structure of the economy, in terms of technologies, tastes and preferences, behaviours and institutions, is a function of the choices and investments made today and over time. With this in mind, it makes more sense to talk about risks and opportunities and the processes that drive clean innovation and steer the economy, conditional on the specific policies and investments, than it does to make unconditional predictions based on predetermined variables and processes (such as future production possibilities and tastes and preferences).

Why investment requirements should not be confused with true costs

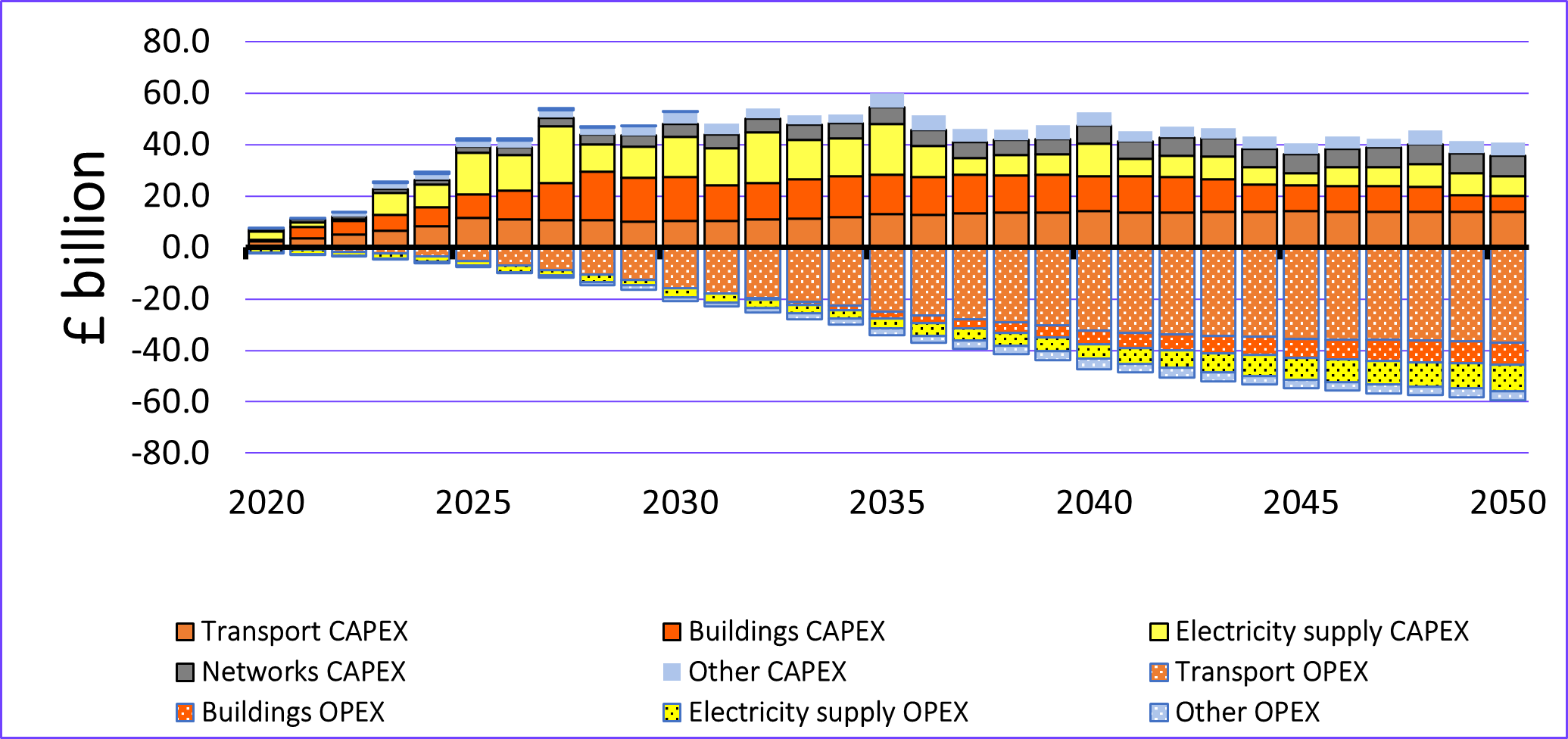

Transitioning to a low-carbon economy will require substantial upfront capital expenditure in sectors such as transport, energy and buildings. Yet this does not reflect the ultimate resource cost. The Climate Change Committee estimates that, before long, operational costs in most sectors in the UK will likely fall (if they have not already) below those of compatible fossil generation. By around 2040, annual operating cost reductions will exceed the additional cost of investing in new low-carbon capital.

Figure 1. Capital and investment costs (CAPEX) and operating cost (OPEX) savings in the Balanced Net Zero Pathway

Source: Climate Change Committee, Sixth Carbon Budget, 2021

There is an economic case for acting sooner rather than later. The IPCC’s modelling finds that while peaking global emissions early (by 2025 at the latest) would entail higher upfront investments, it would also bring long-term gains for the economy, as well as earlier benefits of avoided climate change impacts. Similarly, there is an economic case for increasing the stringency of climate change policies. Taking the example of the UK, research finds that if current climate change policies continue, climate change impacts could cause losses equivalent to 7.4% of UK GDP by 2100, whereas ‘strong’ climate mitigation policies could reduce these greatly, to 2.4% of UK GDP.

Factoring in the ‘co-benefits’ of reducing emissions

A landmark report by the New Climate Economy estimated that the co-benefits of climate action – those in addition to reducing greenhouse gas emissions – in many cases greatly outweigh the costs of reducing emissions. These include benefits to health from dietary change to meet recommended reductions in meat consumption (for the purpose of emissions reduction), and from cleaner air. The economic impact of damage to health caused by local air pollution alone is larger than the estimated cost of decarbonisation. Air pollution generated by fossil fuel-powered transport and infrastructure directly kills nine million people a year. In 2020, fossil fuel pollution killed three times as many people as COVID-19 did, accounting for one in five deaths. Globally, model results for 2030 suggest that health benefits from reduced ozone and exposure to fine particulate pollution (PM2.5) could be as large as 5% of global GDP.

Will it become more affordable to reduce emissions over time?

Estimates of the cost of mitigation ultimately depend on the assumptions made about the availability and costs of different emission abatement technologies, the scale and pace of emission cuts required and the timescales considered. As innovation changes the structure of the economy, and costs of new technologies fall, the parameters of any model used to estimate mitigation costs would need to change correspondingly. This testifies to the limitations of static modelling when looking at long term, non-marginal change subject to uncertainty.

As mentioned earlier, models used to estimate future costs are still entirely dependent on assumptions about low-carbon technological progress during this century. Economists increasingly suggest that existing cost estimates may overstate the true long-term costs of action to cut emissions because they fail to capture future advancements in technologies, and thus falling costs, as well as new innovations developed over time.

While it is difficult to make long-term predictions, the broad trend is that alternative energy sources will become significantly cheaper than fossil fuels. The costs of some key low-carbon technologies have already fallen more than expected, challenging the price competitiveness of fossil fuels even without subsidies.

For example, when the UK Parliament passed the Climate Change Act in 2008, solar power cost between five and ten times as much as coal and gas electricity and offshore wind power was still prohibitively expensive. Since then, the cost of wind has fallen by more than half while solar photovoltaic (PV) costs have declined by more than 90%. The cost of lithium-ion batteries has also fallen nine-fold. For every doubling of solar PV deployment, the price drops by 30%, currently falling by around 10% every year. Today, both solar and wind are cost-competitive relative to hydrocarbons in most parts of the world – even when accounting for the need to cover for the intermittency of supply.

According to the International Energy Agency, which has previously underestimated how fast costs would fall, solar power offers the “cheapest electricity in history” and “renewables will overtake coal to become the largest source of electricity generation worldwide in 2025”.

The costs of electrolising and using hydrogen look set to follow a similar trajectory, while within the last decade, global car manufacturers have moved from reluctance to participation in an innovation race.

The extent to which these costs fall further may depend on the policy commitment to developing and deploying these technologies. Market policies to level the playing field between high- and low-carbon technologies include removing subsidies for fossil fuels (estimated at $260 billion globally in 2016) and imposing a carbon price.

The reality is that the world is not fully rational and fully optimal when it comes to climate policy decision-making. However, providing a clear policy direction can help build investor confidence and encourage research and development and innovation, which may bring costs down in the long run.

This Explainer was updated by Dimitri Zenghelis and Natalie Pearson in September 2022.