For those of us in academia, the term ‘Impact’ can be a strange word implying that our research needs to have an immediate response from the wider public and, preferably, feed into Government policy. For many historians, though, Impact is more of a ‘slow burn’ as work is picked up and disseminated through a variety of sources. Here, Jane Humphries, Centennial Professor in the Department, talks about the translation of her 2010 book ‘Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution’ into Japanese, and the effect it had on Japanese artist, Sawako Utsumi.

When my friend and fellow economic historian Nobuko Hara, Professor emeritus at Hosei University, Tokyo, proposed translating my 2010 book Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution into Japanese I had reservations. Japanese economic historians are very interested in the social as well as the economic aspects of industrialization and look to the British experience as a classic case study. Indeed, they have, through their own research, contributed extensively to the historiography of the British industrial revolution. But I was not convinced that this attention would sustain readership of such a specialized book let alone that a translation could reach a broader Japanese audience. Moreover, the monograph is based on contemporary life accounts by working people. These are often vivid and engaging, but sometimes innocent of grammar and involve local dialects, regional vocabulary, and anachronistic speech, none of which would have figured in an English language course! Translation would prove challenging. Nobuko had no such qualms. She secured a publishing contract from her University Press and recruited several other distinguished Japanese economic historians to help with the translation, including Dr. Chiaki Yamamoto (Osaka University, Osaka), Dr. Takeshi Nagashima (Senshu University, Tokyo), Dr. Makoto Akagi (Matsuyama University, Ehime) and Kentaro Saito (Osaka University of Economics, Osaka).

Translation did throw up a few problems. In one instance, when working on a section about Lucy Luck who grew up in an early New Poor Law workhouse, both Nobuko and Professor Saito were baffled by the appearance of a character who Lucy called ‘Black Garner’. They wanted to know who this could be. All was cleared up when I explained that it was the nickname of the relieving officer who In Lucy's case was particularly uncaring and hard, a man who lived up (down?) to his sobriquet. Nobuko and her helpers triumphed over many problems of this kind and my book appeared in Japanese last year.

The translation is not only personally gratifying. It also gives Japanese historians access to the treasure-trove of British working-class autobiographies which provide a distinctive lens on the British experience of industrialization and shows how such sources can support an analytical narrative of life in these turbulent times. But what of my concern about interest in and readership of a text focussed entirely on Britain? Here my experience is heart-warming and should encourage other economic historians contemplating translations.

The Japanese edition has sold well and already garnered reviews, which reach out beyond economic history. One review appeared in the Tosho-shinbun (in English, Book Review Journal), a well-known general review in Japan, and was written by Professor Nonomura Toshiko who is a historian of child rearing and education at Kyushu university. The review, titled "The child labour study in British Industrial Revolution linked to child labour problem in modern world", sought parallels between the past and the present and canvassed readers concerned with modern child exploitation. Other reviews will appear in the Journal of Ohara Institute for Social Research (forthcoming, next March) and in History and Political Economy, which is the journal of the Political Economy and Economic History Society, (forthcoming). Nobuko is confident that reviews will also appear in titles covering the study of child poverty and gender history. She sees interest within and beyond economic history as grounded in the similarities and differences of the treatment of children during industrialization in Britain and Japan, as well as in the persistence of links between family structures and the deprivation of children. Child labour was utilised sparingly during Japanese industrialization compared with Britain, which given the labour intensity of the Japanese experience seems strange. Some authors have suggested that children in Japan were withheld from early work because they were more treasured and protected than in many parts of Europe, a difference, which if true is intriguing. However, some of the relationships uncovered in Childhood, for example, the deprivation of children growing up in households headed by women, persist in to this day in Western Europe and modern Japan. Hopefully the appearance of the translation will inspire researchers to investigate these and other issues in the future.

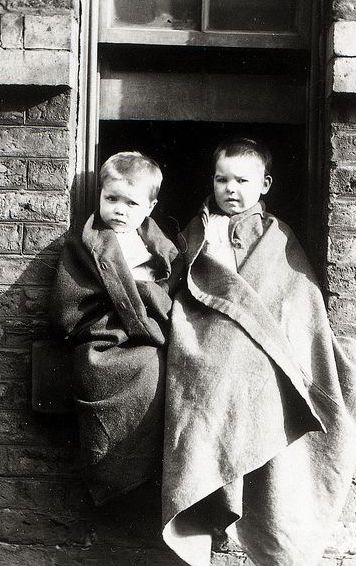

However, perhaps the most interesting feedback, has been a response in a completely different medium from academic scholarship. In an article in the Modern Tokyo Times in early December, journalist Lee Jay Walker reported on the artistic interpretation of Childhood and Child Labour by Japanese artist Sawako Utsumi. In her latest art installation, Utsumi sought to engage with the issue of child poverty and its treatment through depictions of the materiality of deprivation. These include paintings of stark and brutal- looking workhouses and factories confronting diminutive figures who cower in the foregrounds. Most movingly, the exhibition includes a creative rendition of an early photograph (above) of two children wrapped in rough blankets and looking out with sad eyes from a small window in a monotonous brick wall. Reimagined by Utsumi (below), the children acquire an ethereal quality. Swathed in softer material that anticipates the shrouds for which so many workhouse children were destined, they appear as the sacrificial lambs of industrialization. In the accompanying article in the Modern Tokyo Times, Lee Jay Walker uses the personal experiences of British working-class children in the industrial revolution to reflect more generally on the deprivation of children in the past and in the present, a deprivation that she/he suggests often encompasses groups considered privileged and always remains hidden in plain sight. This imaginative response, the product of a serendipitous collaboration in which I was a ‘sleeping partner’, presents economic history with fresh energy to a new audience, something which we should all celebrate.

Jane Humphries’ book is available to buy on Amazon: Childhood and Child Labour, and was the subject of a BBC4 documentary, which can be watched on You Tube. Or you can view clips of the stunning animations the BBC website.

A blog detailing Sawako Utsumi’s project can be read here, and her personal website, showing other artwork, is here.