In this interview, Silas Scott talks to Professor Nick Couldry about Tierra Común. According to their website, "Tierra Común brings together activists, citizens and scholars who want data to be decolonized. Our specific focus is Latin America, but our horizon is the Global South, and everyone anywhere who rejects data colonialism as the latest manifestation in modernity of the Global North’s desire for domination.

Imagination is our greatest tool. Let’s imagine a future where the terrain of human life does not involve extraction of data that discriminates between us and separates us from our own lives.

Let’s imagine Tierra Común."

What do you feel is so important about data in relation to the global South as opposed to the UK or the United States, for instance?

There's a long history to this. I think the transformations going on with data today, which in recent writing with Ulises Mejias, from Mexico, we call data colonialism, are going on everywhere.

We argued this is a transformation of the whole way of human life, basically, so that human life, instead of being somehow outside the capitalist process, except when you go to work or go into shop and buy something, that actually because data can be gathered from us whatever we're doing literally, when we're just sending a few pictures to friends of what you have just eaten, just literally doing anything at all. That changes the relation between human life and capitalism...the capitalist system for extracting data.

Now that's happening everywhere, but the course is happening against the background of first of all, the fact that the power to extract data remains, as in the past, concentrated in particular parts of the world, which tend to be the old colonial centres.

But now, with China added, China a massive imperial power of 3000 years, so that is one very big change, but also the particular ways that data is being used today will inevitably tend to follow in the grooves of taking advantage of those forms of power.

So, let's say if you're a country in Africa with very weak ICTs, very weak telecoms infrastructure, poor internet connection, but the desperate need that people are connected somewhere or the other for disease, health service all sorts of reasons. You're in a very vulnerable position in terms of accepting what's offered to you by the big tech companies from America or China, which means you're in a very weak position in negotiating the data terms. So, the likelihood is, as things go on that they will increasingly lead to even greater reinforcement of those old colonial inequalities, but in a new way that we call data colonialism because the method is different, it's extracting data from human beings, not extracting gold or whatever out of the land.

You mention China, are you particularly worried about China compared to, say, the US?

Well, I think China is very worrying, but not in the sense that China is somehow evil and we have something better in the United States or the UK because the differences are now much less when you look at it.

And that's one way of reading the current trade wars between China and America, is a way of pretending that there’s still a massive difference between the two countries when China is obviously a capitalist society and it’s much more efficient than America and so on.

So, there are worries about China, but they're not really fundamentally different from the worries about the United States, Britain, Germany, what's happening in Africa and so on, because they're all based around this transformation of just extracting data from human beings.

But just going back to the on the face of it the obvious difference from historical colonialism because this is a really important point.. we're arguing, the comparison we're making, is between the beginnings of historic colonialism and the beginnings of this new colonialism. Now the historic colonialism sometimes started with terrible violence and sometimes the colonized literally gave up the gold, they gave things up thinking the invaders were gods.

There wasn't always violence, so things were much more ambiguous, but when there was violence, there was a very clear reason for that which is that these two sets of human beings had literally never met before. They barely could recognize each other as human beings, and as a result there was no social relations to build from, so you needed violence or you needed to lie to pretend you were doing something different from what you are really doing, and they did both. Whereas now we’ve been on the rack of capitalist social relations for two centuries, so we don't need to be trained very much to give up a lot. So that's why we think there's less surface violence.

But there are many people who argue that actually when you combine this with the colonial legacy, when you combine it with issues around race and algorithms and so on, there's a lot of force going on. That depending on how it's built into people’s lives, for example, if they have a very insecure work situation, the extraction of data comes pretty close to violence and in the long run it may actually become violent. We don't know, but we're in the early days and colonialism took fifty years to really get going, of course, so it's early days. So, I'm not saying there's no violence, but there isn't the same absolute necessity for violence as there was the first time around,even though we think it's fundamentally similar, as a form of appropriation.

You talked about watershed moments in this country, but also in the US: Edward Snowden, and other events of this magnitude. Is there an equivalent in Latin America? Is there a particular moment you can draw upon?

These changes are really global, so I think the Edward Snowden event had massive global impact. It's known all the way across the world. It led, for example, to a big reaction in Brazil that for a while, under Dilma Rousseff who was trying to offer a total new model for governing the Internet and potentially linking up with Germany at that time in 2013 and 2014, which never happened fully, but so Snowden and Cambridge Analytica similarly, had a massive global impact.

Although obviously Facebook is very powerful in Latin America - it has a huge reach, so I think those events really were global events. As to whether there was anything specific in Latin America, I don't think so particularly. There have been many other issues with social media, with Twitter in Mexico and so on. Various more local problems, but I think we can see Latin America is part of the wider world.

We've set up the Tierra Común network though because of my particular interest in Latin America which is just one interesting place in the world to be thinking about these issues, and that's where my expertise in language is, so, that's just the serendipitous reason behind the the network.

Are you at all optimistic about the future? Sometimes when you engage with this material it can be quite scary because it feels that there's nothing to be done, that everything is moving in one direction. Could you offer any thoughts on how things could get better?

Well it is clearly a long-term process. You’ve almost got to think in the longer term. Which also means that we need to think that if we don't resist soon then we have good reasons to lose hope, that this is a big change going on, so we need to think about resistance and that's going to take a while to figure out how and then it will have to be a very long fight.

On the other hand, we argue in the book and the website, that the most important tool human beings always have is their imagination. It is the ability to say, well, this appears to be unstoppable, impossible to think beyond and so on, but we can think, and we can think beyond it. We can imagine the world where this is no longer the same, and therefore that's exactly what we need to start doing. But we can't do that on our own. We can only do that together because human beings can only change big things by thinking together and helping each other develop metaphors, ideas and its partly imagination, and then that fuels practical things.

So, if you imagine someone were to say well, I've left Facebook this afternoon because I can't go on using this platform, this colonialist platform if you call it that. There's plenty of reasons for doing that, but that persons friends will probably say, well, that's no good because I'm relying on you to pick up my Facebook message because I'm organising the kids party for this coming weekend and I'm not going to do it through some other platform so you know and so on and so forth were all embedded in these things. Same thing about Twitter for some of us it's essential, for others it's anathema. But, you know, it's really inconvenient when someone you're dealing with is not using Twitter. We've had these debates within Tierra Común.

But that's part of the way it is, because this is a social order, so we're bound to get hit this way. So, the way to approach it with imagination is to say OK, we need to help each other deal with the costs of stepping down from these platforms, there's going to be a long-term battle. We need to find other ways of connecting. It's something we all need to think about together. That way we can gradually change things and reduce our collective dependence on these platforms, and that's going to be slow. But we shouldn't worry about that because in every movement, resistance in the past has had to use the tools that were lying around, whether it was TV or newspapers or cars or whatever it is. You have to use what you got. There's no choice. You can't change society before you change society as it were. So, you you just have to accept that and just keep going. And so, there are reasons for hope provided we see the reality as it is and start to help each other. Think about that and imagine a different future.

Do you think those platforms, Facebook, Twitter etc. can be reformed, or do you think there's something inherent which cannot be transformed for the better?

Some people, including on the left, have argued that we need to reform them so that we own data socially. Evgeny Morozov argues for socialising the data centres, somehow taking them over for the social good. And there are some countries like Estonia, they've experimented with a more social approach to owning at least public data, public health data. But I'm pretty sceptical as to whether you can take over platforms like Facebook because they were built for one purpose only which was to connect people as the means to extract data to fund, to create advertising, to generate income. I don’t see how you can, it's really set them up on the scale they currently work. Maybe the scale is part of the problem.

There’s a difficult question about search engines. How will we build a public search engine that wasn't Google that was under public control that had some of the power of Google? This is a very, very difficult question. We don't know the answer yet. We clearly need search engines. We can't exist in the world without some way of seeing what's out there. Maybe we don't need quite such a good search engine as Google provides. Maybe something that's a little less good would also be OK.

These are massive social questions, but I am sceptical as to whether the answer is simply to socialise these platforms. I think there's something fundamentally structurally wrong about the way they've been built up and the scale they've been allowed to get to, and that is the problem. So, we have to dismantle them in part.

Relating this all back to the Tierra Común project, what was the initial thinking behind it? When did you decide this was something you wanted to do? Where do you see it going in the future?

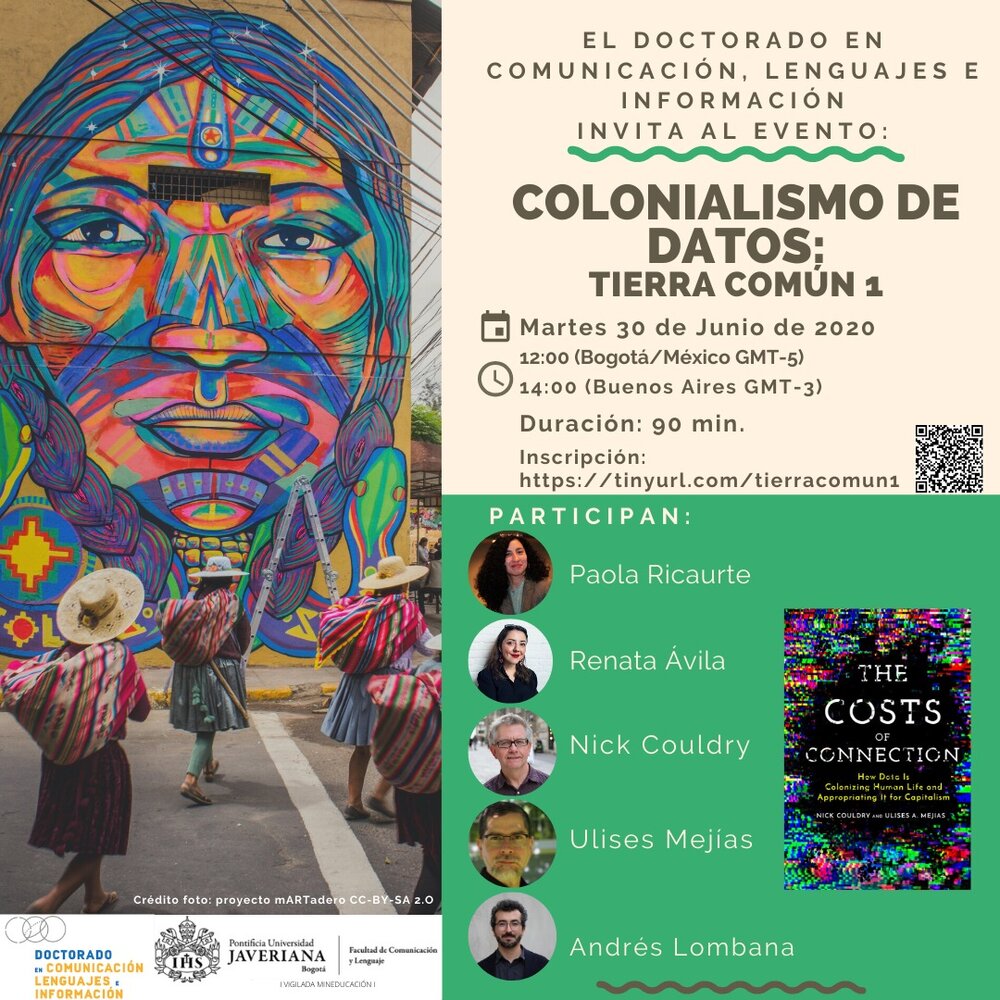

As to how it started, it was very simple really, and I explain this on the blog on the site that I just done a talk in Mexico City last November about data colonialism with Ulises and it seemed to go OK. And I was saying to our host there, Paola Ricaurte, that it would be nice to do some more talks in Latin America, because I've learned Spanish recently and I thought this is a perfect audience for this topic as there’s a lot of interest. And she said, well, it's not going to happen very easily because none of us can afford to fly within Latin America, the tickets are too expensive, we just can't do it.

And I was really shocked by that because living in Europe and I guess it would be the same if you lived in the United States or Canada, we take it for granted that if we feel like going to Copenhagen or Rome because something interesting is happening, we probably can, and it's not a big deal and we can until COVID-19 of course. And I realise, how profound the difference in resources is between Latin America and Europe, and it was quite shocking to realise how naive I’ve been.

But rather than just criticise, just feel guilty, we decided the much more interesting thing to say was OK, let's think of a solution and we suddenly thought that evening, maybe we could just create a website, a really simple idea where events will be archived. They might happen in Ecuador or Colombia or Buenos Aries amongst the people on the ground (subject to COVID-19 which we didn't know about at the time) and people with the money to fly from Europe could fly, fine, they pay for it but no one else would have to pay for it. It will be happening locally, but it will also be recorded and it will go up on this website. It would add to the growing archive of events that think about this massive development that's going on where we really need to have solidarity to think together on,but it wouldn't involve people having to pay for expensive plane tickets.

It seemed a good idea and very very simple.The idea very simply was that if we could do this, by creating a good enough website that people would find attractive with a very simple concept, people will feel that they’re building as they take part. We were going to call it Tierras Nuevas (new lands) but that sounded a little bit too colonial so we changed it to Tierra Común: common Earth- common domain, which is entirely open for anyone to interpret however they want.

So, the events will be Tierra Común 123- ad infinitum. Wherever they happen, they are just Tierra Común-another part of this common earth we find out. We thought with a really simple idea like that that everyone could feel they are included in it. The events, could literally happen anywhere: in a village or university, a hospital wherever you like, but as long as the spirit was right, that people were thinking about the concepts and that it was recorded, it will be part of this bigger space and it was really that simple.

Because I had a bit of teaching to do, I didn't get around to making any progress until end of March. From late March onwards, I started working with Anthony Kelly who’s just finished his PhD in our Department too who's a very good web developer. But we realised suddenly this was urgent for a different reason, which was that none of us were going to be able to meet even if we wanted to and even if we had the money. Because no one could meet because of COVID-19. So, we suddenly realised that this idea of a common territory where people come together to think together in spite of everything else was important. The basic website is built with squarespace, which is a reasonable website developer to use. And using that infrastructure to create a space of the mind, where we could come together and think together and be in front of each other, that's why we did it.

So where do you think the project will go in the future?

Well, the future is completely open. Of course, we do not know where it's going to lead. We thought from the beginning it was an interesting idea because it's completely open. No one owns it. It's not a western idea. It's an idea thought about by two Mexicans and one English person, becuase Ulises another Mexican has joined to support it. The website was built in Britain but with a lot of input from elsewhere. The network that's already forming very fast already has 30 people in it. Membership is growing by the day, most of those of course, are in Latin America that's the plan, but not all will be in Latin America. We've had our first event in Bogota, Columbia.There's another one hopefully in Costa Rica and there could be many more. We will see what people themselves want to create.

We have got an open agenda, but we hope it's going to become a place where people feel they can go to see interesting events around data colonialism and resisting it. Places where if they have a piece of writing they want to put up for reaction, they can do that. Maybe an artwork they want to share that somehow symbolises this struggle-they can put that. We've created pages where that could be done. Maybe they want to archive some teaching resources, they can do that.

Gradually we will create a space that is a focus for people to come together and think together about these massive challenges with the history and archive behind it. If this really takes off and, in a year, builds a lot of people, maybe it will be really the beginnings of a movement, a focal point for movement around these issues. That's the idea, it may not happen, it may happen, we just don't know, but it will be down to what people together are wanting to do, but no one knows this.

I'm very proud of LSE being a part of the beginning of something like this, because the reality is that being a rich institution in the global North, we do have the resources for me to pay a developer to get something like this going and then to market it and things like that. We can help and we can give those supports but it's very much not about the global North, it’s about a space of dialogue that is mainly anchored in the South. I am happy to be part of it in some way, and it will go wherever it goes.

That is really interesting because, as I mentioned, we have the Edward Snowden moment but issues with data are not only relevant to elections across Europe or the United States - it is much wider than that. It would be easy to assume that the issue of data is only something that affects people in the West which of course, as you have explained, is incorrect. But we have a tendency to latch onto those ideas and not think more more wisely about how this affects people across the globe.

Well just to give you some examples, Joao Magalhaes, another PhD student, formally in the Department who got his PhD in December and is now in Berlin. He and I published a piece for Jacobin magazine in May or April about what's happening to social welfare around the world, partly through COVID-19, but also partly through this change - data colonialism. There are signs that because data power gives a massive new means to intervene in the world to big tech companies, big tech companies are positioning themselves as the perfect right hand, if you like to government. This happened with COVID-19 in the idea of Apple and Google coming together with the contact tracing app which only partially succeeded, but there are many other examples of this already going on.

For example, in Latin America where because the welfare system is less well funded than in Europe, because inequality is even greater than in Europe and in America, the philosophy of using data to somehow get at the poorer sections of the population to monitor them more efficiently to help them live their lives better in harmony with the welfare state, is offered in a positive light of course. But this all depends around collecting data, through all of it. And we are arguing that this is a shift in the nature of wefare with big tech being at the core of this. Big tech of course is most of the time being based in the West, not based in those Latin American countries.

Or you could turn to India where the Modi government has been extremely excited by data questions. Four or five years ago it set up the Aadhar system for digital biometric IDs for each person, which is a condition of getting transport tickets, getting on the welfare system, voting and so on. But again, the Indian state is trying to link big tech power to the power of the state. So, you only have to get outside this small bubble of Europe or United States to see they're already very interesting new models of how the state and data corporations work together, which are not necessarily good and that you don't even have to look to China for this. You can look at countries that are regarded still as more or less democratic. But these experiments were already going on, so there's lots really to talk about. And Europe is just one, often a less worrying window on these developments then what's going on in the rest of the world.

I don't worry that the government is necessarily using my personal data, but I can understand with those examples, where organizations are working with the government, they both can have access to your data. They can be using it for all sorts of reasons, which is quite worrying.

If you just imagine, let’s say you are older, maybe you have a health issue. You are worried about how that health issue will affect whether you can stay in your job because it's going to affect your relevant skills. You had to disclose it to your doctor, but once health data starts moving around, of course it's meant to be anonymised, but it's easy to deanonymise. Maybe you use a training device like a Fitbit or something like that which you did it because your employer said well... You want health insurance, don't you? Well that means I have got to check your health, so you're going to have to use a Fitbit and give up this data.

Fitbit is giving its data to all sorts of companies and you can't trust that one of the won’t end up being connected with the state. This could affect your social services, your welfare benefits if maybe you lose your job. You may never get another job, all sorts of things that happen particularly, If you're already vulnerable in some way or other. So, one doesn't have to look very far in the future to see some very dangerous scenarios here.

They don't have to happen through intention either. The government doesn't have to attend intend these things; it just needs to allow various types of corporate environments to grow and for corporate economies to grow. And naturally they will create connections and unless you stop those connections and block them they will happen.

We are worried about Huawei at the moment, but I was laughing hearing some expert on the radio saying, well, actually the idea that Huawei can listen into what you're saying down the phone line is ridiculous because if it’s something you want private, you're probably going to encrypt it or use WhatsApp if it's something that you're nervous about. Most other things are probably very little interest. That may not always be true, but other areas like health data are incredibly sensitive. All health data is dangerous if in the wrong hands, but that's not what Huawei is planning to do and yet we're not worrying about these other things. We are worrying about Huawei building our copper wires and so on. So, it's a distraction, I think.

And of course, it's easy to say that data is particularly good. The argument is that it's particularly helpful because it's reforming and its standardising content which on the surface looks like a particularly helpful tactic of modernisation in order so everyone is transparent and everyone understands the government is able to help people when they need it. But obviously things aren't always that that ideal.

I think what's happening is on the global scale and it's such a big change that it's really, really hard to see it. It is almost beyond our vision. It's just too big that the whole structure of power is changing. Power is now being exercised through data, not through the other means of power like gathering bits of paper, guns and so on. Those continue, of course, but there's much more powerful tool which is gathering data which can be transferred from any point to any other point in a symmetrical way so, it can be aggregated and so on and so forth. This is radically changing the very nature of power and the way power can work, so it's changing how societies can be organized, and what governments can be.

That's a really uncomfortable thought. We tend to want to assume some things are staying constant as we think about the bad or good things in the world. But actually, the biggest thing, how power works, is not staying constant right now but its morphing into higher dimensions, so that's another reason why we need the imagination, because the change is very large and very deep, and it's almost impossible to get a handle on without using the imagination. And you can be sure the politicians are not talking about this. It’s really not in their interest to talk about this and it never will be.

I wonder how many politicians in the UK are actually aware of all of this. Technology and data can sometimes seem quite niche, and because the MPs that represent us aren't necessarily representative of everyone in the country, especially in terms of age and demographics, they may not be tuned into this issue.

You mentioned Huawei. Lots of MPs are very angry about this issue, but I'm not sure they would be so angry about the other issues you touched on because they may not realise what's going on?

I think that's a good point. I mean obviously a lot of these are different, genuinely difficult issues. We have a luxury as academics to read and think about these things and research them and MPs don't have the time to do that, and it's not fair to expect them anymore than in the US. Senators don't have a lot of time, although they do can fund research. They probably should have been better informed than they were when they interviewing Mark Zuckerberg, but it is difficult. At the same time, these sort of crude stereotypes of China is bad- US is good is really so far from the truth of what is actually going on in terms of the technology that they're almost silly. They get in the way of seeing what's going on. So, it is really important to have this debate.

It's important the Tierra Común website is not aimed just at academics. It has been started by some academics, but already in the network we have quite a few people who are activists on these issues and it's going to be open. We hope for citizens in any country who speak the three languages of their website: Spanish, English and Portuguese to get involved and to attend events, suggest ideas. It's really important that so called ordinary citizens- If there is such a thing- can take part because this has to be a civic movement.It has to go way beyond universities if it's going to make any difference at all to governments and society. Hence the idea of something as simple and open as this Tierra Común, common earth, common territory.

I think that’s a really good note on which to wrap things up, because this is a really nice way to be optimistic about something that can be quite scary.

I am optimistic because I know that until November (2019), I didn't have this idea, we had it two of us together. Seeing a problem that now exists. People seem to like it. We've done it. We can do much more than we can yet imagine.

So, we just want to keep going and right now will be our challenge to do things that are difficult that we didn't know we could do, and some of them are good. Not all of them, but some of them can be good. So, let's make the most of the good things that we can do together. And I'm proud to be part of this.