Over 650 people from around the world – from El Salvador to Cape Town, from Jerusalem to Moscow – attended the second Urban Age Debate on Humanising the City on 27 April 2021. Focusing on the interactions between the design of public space and its impact on social life, the virtual event featured presentations from three architects and urban practitioners – Rozana Montiel of Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura in Mexico City, Amanda Levete of AL_A in London and Elizabeth Diller of DS+R in NYC – and a discussion with leading urban author and commentator Suketu Mehta. The event was chaired by LSE Cities Director Ricky Burdett and introduced by Executive Director of the Alfred Herrhausen Gesellschaft Anna Herrhausen, co-organisers of the Urban Age Debates series ‘Cities in the 2020s’.

Key Takeaway 1: Re-imagining forgotten and underused urban spaces offers potential for connection and integration

The Covid-19 pandemic has amplified the value of public space for our well-being as urban citizens at a time that investment in the open public realm has been challenged. The projects presented by the speakers revealed how simple architectural gestures have transformed forgotten or underused spaces and structures into places of connection and integration.

Suketu Mehta argued in favour of even the smallest interventions which can add value and complexity to urban life. Describing the pedestrianisation of a busy traffic junction into a people-friendly Diversity Plaza in Jackson Heights, New York City, Mehta noted “Jackson Heights really lacks any kind of public space, there aren't any big parks, and there aren't even small parks. Diversity Plaza just got a few benches, really nothing much has been done to it. But if you want to know what's happening with the Bangladeshi elections or relationships between Tibetans and Chinese, you can go to Diversity Plaza and find little groups of immigrants debating the politics of their homelands. It's an incredibly human space in the big city.”

Diversity Plaza, Jackson Heights, Queens, New York City: 'an incredibly human space in the big city'. Credit

Diversity Plaza, Jackson Heights, Queens, New York City: 'an incredibly human space in the big city'. Credit

The High Line project in New York City reimagined a two-kilometre stretch of obsolete industrial rail infrastructure into a linear park, becoming the city’s most popular attraction with views of the urban landscape from eight metres 'up in the air'. The vision for the project, Diller explained, was “To take this piece of unused property, and bring green space into an area that was really underserved by green space, but also with an argument to serve as a catalyst”.

On a smaller scale, Rozana Montiel’s surgical interventions in social housing complexes in Mexico – the conversion of a redundant sewage canal in Fresnillo and a gated courtyard in Mexico City – demonstrated the value of retrofitting underused space. Describing the impact of the Fresnillo project, Montiel stated “Unclaimed urban spaces can be transformed into inclusive places, rich in function and diversity. Places of resilience where despite the surrounding violence, young people can teach their dance classes and children can play”.

Key Takeaway 2: Unplanned and unexpected uses of public space contribute to social life

Versatility has been key to successful public spaces, allowing and promoting unplanned and unexpected uses add excitement and spontaneity to urban life, while many purpose-designed spaces are overly prescriptive and constrain human behaviour.

Levete exploited the opportunity of re-engineering the entrance to the imposing Victoria and Albert Museum in London by turning a disused boiler yard into a shared space that links the museum to the city. “The way the public have used the courtyard has been transformative. It’s changed the way people see the museum and it’s changed the way the institution sees itself,” Levete noted, reflecting that “It’s sometimes the things that you don’t do that allow the unexpected to happen, and the space to be appropriated by the public”.

Diller expressed a similar sentiment when her studio learnt that their project for Zaryadye Park had stimulated unexpected uses from Muscovites: “There was an invitation for the public to come in and use the public space in a kind of un-inhibiting way, very different from other parks in Moscow. People are feeling so free in this space that they can really enjoy the space and each other. So to us, it was a victory”.

DS+R's design for Zaryadye Park in Moscow includes a floating bridge above the Moskva River. Photo by Iwan Baan.

DS+R's design for Zaryadye Park in Moscow includes a floating bridge above the Moskva River. Photo by Iwan Baan.

Key Takeaway 3: The public realm of city is a democratic and contested right that reflects opposing interests, 'Urban space is public and democratic like air and water, until it is cut up and privatized' (Liz Diller)

Architects have traditionally focused on the design of the built environment in cities with limited understanding of the complex structure of public space as a social, environmental and cultural artefact.

Suketu Mehta highlighted the division between the disciplines that claim responsibility over the public realm, “I’ve seen now that language itself seems to have become splintered. Architects talk in a particular kind of language, sociologists talk in a different language, writers talk in a different language”. To his mind, this distortion contributes to “The construction of vanity projects being declared as an essential service. It’s an example of how not to humanise the city”.

Underscoring the role of the designer in shaping cities, Diller stated at the outset that “The work of my studio has always been guided by the principle that urban space is public and democratic like air and water, until it is cut up and privatized. All of us are responsible to protect the public realm”. She further explained “Architecture is so slow and geo-fixed, and society is changing so fast. How can we think forward in terms of building, how can we imagine architecture of distinction without generic form going forward? That's our first obligation”.

Commenting on the role of designers in shaping public life in the city, Levete expressed the view that “It is our responsibility as architects to spark these conversations, to provoke debate about these topics and bring the private and public sector together”. Nonetheless, Mehta cautioned the panel of the dangers of limiting the discussion of the public realm to rich urban areas and excluding discussion of more peripheral areas like suburbs, or public institutions that promote cohesion.

Key Takeaway 4: The significance of the relationship between the physical and the social in public space has been made more evident during Covid-19 lockdowns

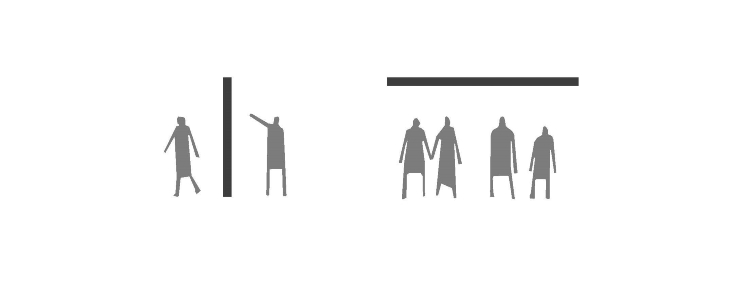

Given the restrictions imposed on using the public spaces of the city during lockdown, Burdett asked the speakers whether there had been, perversely, an ‘intensification of the urban experience’ which had in effect magnified the ‘relationship between the world of the social and physical’. Montiel argued that her studio has always prioritised this relationship through the concept of ‘placemaking’. In Montiel's Common Unity project in Mexico City, “Through placemaking, we built with the community, not only for it. Our design replaced [rigid] barriers with [porous] boundaries. Placemaking is understanding that the value of architecture is not only laying bricks, but activating a social construction”.

By re-orienting vertical barriers like gates and fences horizontally to create a roof and enclosure, Rozana Montiel framed an environment which promotes social interaction and cohesion in the Common Unity project in Mexico City. Illustration image by Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura, photo by Sandra Pereznieto.

By re-orienting vertical barriers like gates and fences horizontally to create a roof and enclosure, Rozana Montiel framed an environment which promotes social interaction and cohesion in the Common Unity project in Mexico City. Illustration image by Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura, photo by Sandra Pereznieto.

Levete connected the ‘perfect storm’ of growth in online shopping and the impact of pandemic lockdowns on the economic viability of the typical inner city high-street. She focused on the plight of department stores which are increasingly going out of business and becoming redundant as a building type. Levete emphasised that demolition constituted wastage, and argued that even large, deep buildings like department stores could play a key role in revitalising inner city areas. Her creative concept for retrofitting an empty building into a community food hub was based on the notion that, "Food brings people together. Integrating the urban and nature has never been more important and I hope this project speaks to the potential for creating new social typologies that capture the mood and the character of our time”.

Section of a derelict department store turned community food hub. Image by AL_A.

Section of a derelict department store turned community food hub. Image by AL_A.

Key Takeaway 5: The future of public space in the city is dynamic, diverse, and complex

The pandemic has intensified and diversified the uses of public space as urban residents sought refuge from constrained and often cramped living spaces. Whether these changes will endure over the next decade remains to be seen, but this debate highlighted how designers can integrate the new uses of public space into long-term change.

Montiel closed her presentation with seven principles learned through her projects to humanise the city: “We must seek content in context, change barriers into boundaries, start with a shift of perception, approach the landscape as the program, re-signify materials, work with temporality and hold beauty as a basic right. The city is humanised when the space becomes a place”.

Suketu Mehta concludes, “We need to think of how to humanise three types of places: the bazaar, like Amanda re-envisioned, the park or the playground, and the library, as Eric Klinenberg has pointed out, are palaces for the people. In the post-pandemic world, we more greatly than ever need to connect”.

Follow @LSECities on Twitter and subscribe to the LSE Cities newsletter to keep up-to-date about the Urban Age Debates as the event series continues in May with the next virtual debate: Localising Transport.

Speakers

Elizabeth Diller (@DSRNY) is a partner of the architectural practice Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) based in New York City. Diller has been committed to an exploration of how democracy and the public realm intersect, realising spatially-inventive and socially-progressive projects in cities across the world including the High-Line in New York City and Zaryadye Park in Moscow, as well as educational and cultural buildings that prioritise connection with the city and the creation of social space.

Rozana Montiel (@rozanamontiel) leads the Mexico City-based architecture studio Rozana Montiel | Estudio de Arquitectura which has investigated how elegant, modest architecture can contribute to the creation of socially-inclusive urban spaces. She has transformed abandoned open spaces in a public housing project into active social facilities through the Common Unity project in Mexico City and completed a rural housing project for earthquake victims in Ocuilan, Mexico.

Amanda Levete (ala.uk.com) is one of the United Kingdom’s most respected architects who has consistently pushed the boundaries of architectural, technical and social innovation. A regular commentator on design and urban society, she is the principal of AL_A, which re-engaged the Victoria & Albert Museum in London with the city through its award-winning Exhibition Road project, re-animated Lisbon’s waterfront with the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, and is exploring the potential of regenerating inner cities across the United Kingdom.

Suketu Mehta (@suketumehta) is a writer, critic and urbanist who focusses on the social and ethnic complexity of the contemporary city, and the deep connections between urban form and cultural vibrancy. Author of ‘Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found’, winner of the Kiriyama Prize and finalist for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize, Mehta explores how cities sustain diverse urban communities, delving deep into the dynamics of migrant communities in the global cites such as New York City, Mumbai, and Rio de Janeiro.

Chair

Ricky Burdett (@BURDETTR) is a Professor of Urban Studies at the London School of Economics, Director of LSE Cities, a global research centre at LSE, and co-founder of the Urban Age.

Welcome

Anna Herrhausen is the Executive Director of the Alfred Herrhausen Gesellschaft and the head of Deutsche Bank’s Art, Culture and Sports department.

Note: quotes have been edited for clarity and cohesion.