Youth across the world are getting increasingly mobile. Many imagine, plan for, and live transnational lives, remaining attached to several societies at once. This is particularly true for young refugees and migrants. Social media can play a vital role in establishing new and maintaining existing networks across geographies; as people move, social media holds the potential to stay connected to a global world.

Our study on social media usage in Arua, Uganda, reveals that close to 90% of young people are on social media. This can partially be explained by the fact that national figures covers the entire population, whereas our project focuses on a young urban popualtion. Still, the high share of people on social media highlights the need to better understand how social media is used, and for those working in humanitarian crisis, implications for inequalities in access to information, networks, services and jobs. Our study shows that social media is important for making decisions on intentions to remain or leave the city, and further that differences in the quality and quantity of usage - how often, for what purpose, and between who - social media is used, seems to be linked to socioeconomic factors. As Arua continues to grow, so will likely the disparities in whether and how young people use social media to make important decisions about their own future.

Transcending in-person relations

Studies on social capital show how it extends beyond individual social connections, impacting many important aspects of life including employment, schooling and community activities. Social media extends social capital across distances, connecting people whether familiar or unfamiliar in person, thereby nurturing and broadening social networks beyond physical encounters and relationship.

Our research shows that respondents use social media to actively communicate with family and friends in Arua and elsewhere. These expanded networks can be tactical in that they may support future opportunities in different places, both Arua and the places people came from or are thinking about going.

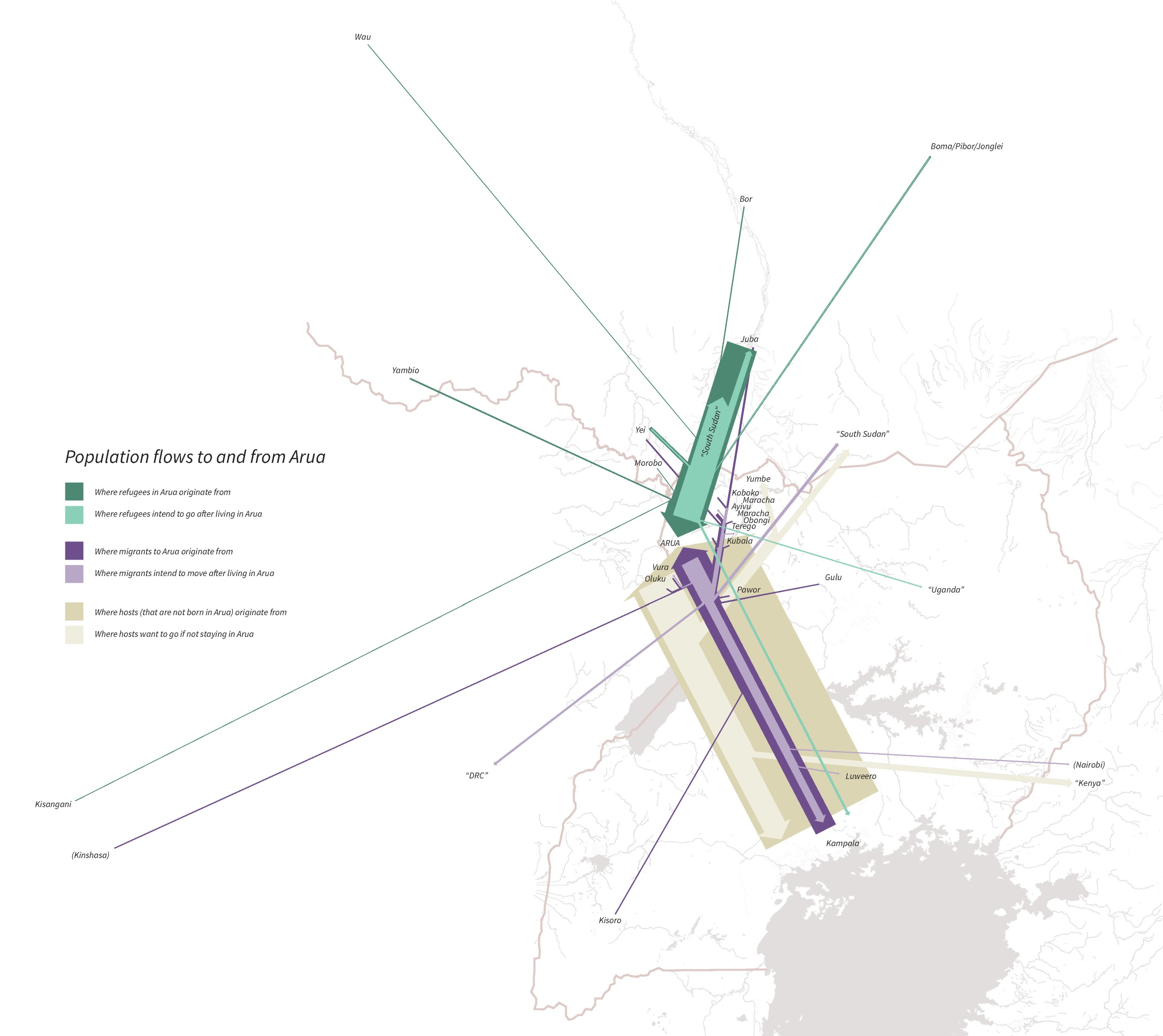

Figure 1 shows where the repondents came from and, for those who intend to leave, where they want to move. Our study shows that 68% of respondents consider Arua as a stopping station or point of departure. The intention to leave is unsurprisingly highest among refugees (90%) followed by migrants (49%), and host population (20%). While most refugees dream of going back to Juba in South Sudan, migrants and hosts indicate their wish of moving to Kampala, other cities in South Sudan as well as Nairobi. This reflects the larger migration situation in the region, and the educational and career aspirations that characterize young people. Additionally, social media can help facilitate the relationships forged in places people have left (e.g. refugee’s family and friends in South Sudan) or to places where they know someone (e.g. people from Arua who have already moved to Kampala).

Figure 1: Map of Uganda and neighbouring countries showing where the repondents in our study cames from, and where they intend to move

Schools as a platform for building social connections

Using social media without an existing network established through in-person meetings may support access to information, certain activities, and to a degree, to build relationships and developing social capital. However, physical meetings are still important for building and strengthening networks. Schools present one central arena for interactions, building social relations and exchange among students.

Our study suggests that students and graduates use social media to keep in touch with networks established at school. These networks are seen to extend beyond cultural, socio-economic and citizens groups. In a context where local youth were expressing some skepticism towards refugees who are perceived to be better off, such school-turned-social-media were still found between local and refugee respondents. This suggest that potential of expanding relationships to a wider socioeconomic group in school and, importantly, maintaining such relationships over time and physical distance.

Access to education and employment

Access to higher education and employment are uneven and limited in Uganda. According to the Global Education Monitoring Report (2019), as of 2016, less than 1% of refugee youth had access to higher education. The national rate of enrollment in primary education is 91% (2013), while that of refugees is 66%. For secondary education, the national rates drop to 22% (2010) while the refugee rates drop to 20%.

In our study, 35% of respondents said they were unemployed, and a majority of young people from poorer households had lower level of education. Within the 35% who were attending school there were more refugees compared to migrants and locals. Interestingly, refugee households generally had a higher income compared to host households. However, the majority of refugee students attended lower education, and a majority of students attended higher education are host population. There was also a tendency for women to be more represented among the unemployed and less represented among students.

Unequal opportunities

The quality of social media use is impacted by digital divides, e.g. between urban and rural areas or gender, and choice and social background of its users. Those from less advantaged families have fewer digital skills, and use the internet less for capital-enhancing activities such as looking up information online, and more for leisure or communication purposes.

Moreover, different user groups tend to reinforce homogeneity on social media channels; those who can afford to be online generally consume content produced by groups with similar socio-economic situations. At the same time, studies suggest that platforms are skewed toward content produced by younger, wealthier, and better-educated citizens.

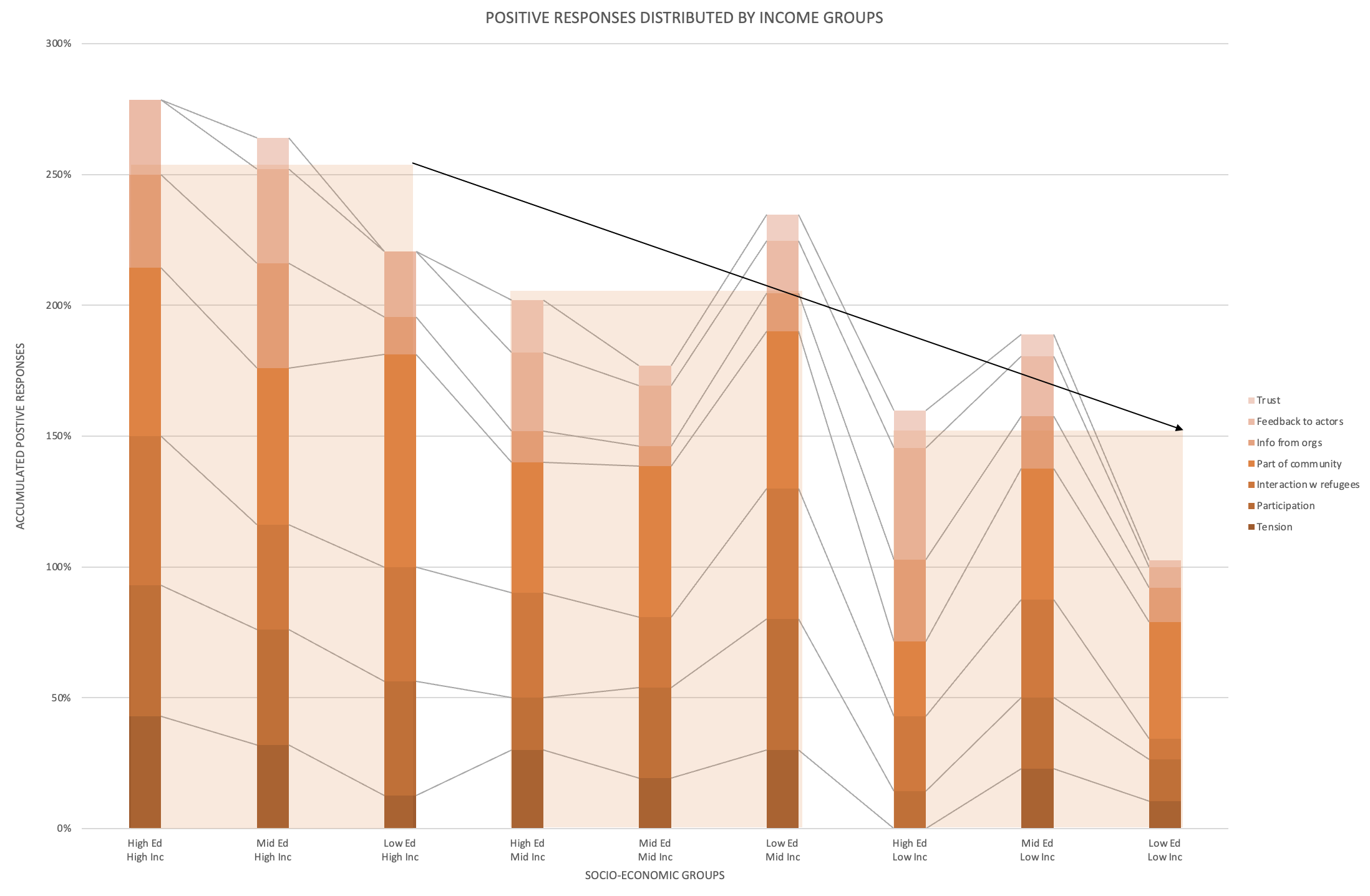

While most of our respondents used social media and digital communication on a daily basis, the way it was used depends on several factors. There was a distinction between social media use in terms of quantity (time spent on social media), quality (what they spent time on), and networks (as a means and an end). Education and income was among the most significant factors for the variation in the quality of social media use, where higher income was positively correlated with higher social media use as well as positive responses to the use of social media (see Figure 1). Those with higher income could afford to be on social media more often and have greater exposure to different information. Language was said to act as a barrier to expanding networks, in this case to Kampala – a favored would-be destination for many of the respondents seeking work and education.

Figure 2 Accumulated positive responses to use of social media across topics distributed by income groups

Planning for the future

It is among students that the respondents most frequently expressed an intention to leave Arua. Regardless of nationality and legal status – our study shows that the vulnerable stay in Arua, and those with various forms of capital, including larger social networks and access to education, have more clearly defined future trajectories elsewhere. Noteworthy, the majority considered social media to be important for decision-making.

The use of social media to inform decisions ranged from looking for jobs or study opportunities elsewhere to a more prosaic use of social media to keep in touch with people in other places and in Arua. Among young Ugandans in our study, there was an expressed desire to be part of the expanded networks for refugees, to a) expand “real life” networks to include refugees in school, then b) be included in such refugees’ social media networks, in order to c) potentially utilize these newfound social media networks to get better jobs, training, or simply move elsewhere.

The findings suggest that social media can help inform choices about the future, and respondents holding more social capital built through physical interactions, including through school and moving, benefit the most.