Less than 6% of Uganda’s population use social media. While the yearly growth among social media users is said to be explosive, this is a low number by global or even regional standards: in neighbouring Kenya for instance, 21% of the population used social media. But national averages mask important geographic and demographic distinctions. In our research in Arua, a major city in Northern Uganda, we have found that social media is used by 87% of the city’s youth. The difference in numbers is substantial – if not surprising.

Arua is an urban island of relative security within the West Nile Province for people escaping conflict. Caught in a historical tri-state flux between Uganda, DRC, and South Sudan, the province has been a source of extraction and exploitation by colonial and post-colonial regimes. Suffering from underinvestment and few opportunities, it has served as a hotbed for rebellions in the latter part of the 20th century. As the situation stabilised during the 2000s, Arua’s position as a migratory hub was strengthened. Today, Arua fashions itself as vibrant and inclusive. The city is home to 120 000 people; a small number considering that 12 million of Uganda’s 46 million citizens are considered urbanites. But most of these places are, like Arua, small urban centres. Interesting to this research, Arua is a city where disparate socio-political backgrounds, allegiances, and goals are brought together. It is home to internally displaced persons (IDPs), returnees from DRC, migrants from within Uganda, and approximately 12% refugees according to the 2021 Arua City Central Division Census.

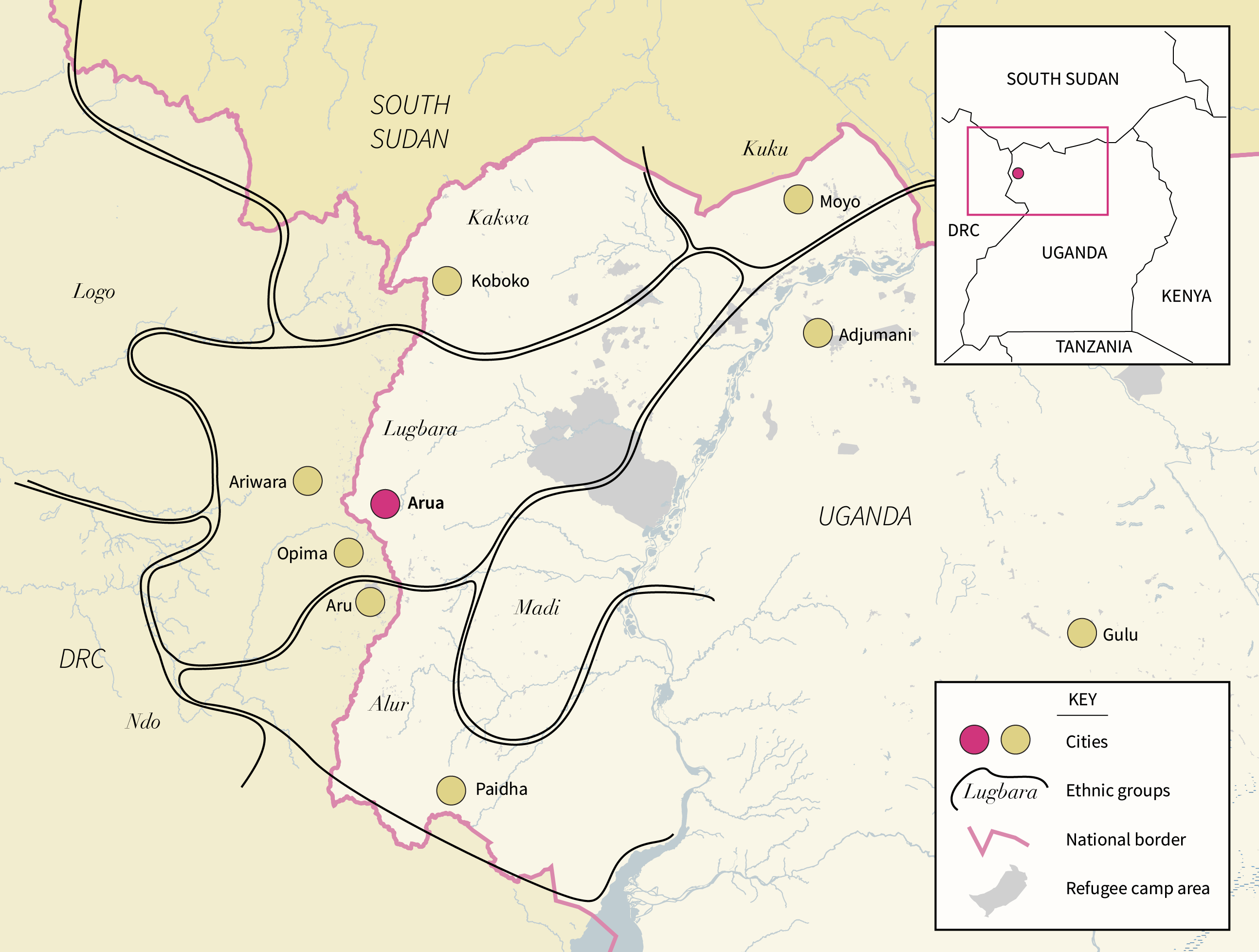

West Nile region, and neighbouring areas in DRC and South Sudan, showing major urban centres (yellow), areas designated for refugee settlements (grey), and cross border identities (black lines).

Uganda, and in particular West Nile, has become an important destination for refugees, most of whom are from South Sudan. According to UNHCR, there were close to 1,5 million refugees and asylum seekers in Uganda by the end of 2022. This makes Uganda the biggest host country on the continent. While a great number settle in camps where they qualify for protection and humanitarian assistance by the government and UNHCR, refugees are free to settle elsewhere in the country upon registration. Many Southern Sudanese who enter West Nile opt to settle in Arua, where markets, work and schooling opportunities are present. Most of the South Sudanese youth that we have engaged in our research come from urban backgrounds and reported feeling more at home in a city than in rural camp settings.

Bodabodas (motorcycles) are popular for transportation of goods and people in Arua. They are also used for illegal cross border trade. Credit: Africraigs/CC BY-SA 4.0.

In our study, we found that among these young refugees from South Sudan the uptake of social media is even higher than among young host groups. Considering that our respondent groups were all young urbanites, it may not be surprising that their use of social media by far outweighs national statistics that include rural and older populations. However, the substantial difference shows that understanding the role social media plays in people’s lives is an important area of research relating to inequalities and displacement in cities such as Arua.

Our research shows that social media is important in a variety of ways to urban youth – much like it is elsewhere in the world. Our respondents used social media to nurture social relations, to look for jobs, and expand their geographic scope of opportunities. The differences in how youth in Arua regarded and used social media related to socio-economic standing rather than their refugee status. To the poorest – those who used social media the least – its allure lay in the untapped economic potentials and promises of a brighter future that new connections might provide. To middle income groups social media was a useful information channel when job hunting, but their experience was that few actually secured jobs this way. To those from better off families, social media was a natural part of their daily social and cultural tapestry, making it hard to gauge its impact; it was always present and one of many tools in decision making processes for a group seeking futures and opportunities outside of Arua, and who were often successful in achieving such goals.

With social media being so widespread and important to Arua’s youth, we have asked ourselves the following: how does social media play into young peoples’ abilities to access social networks and opportunities in the city? How do youth use social media to navigate and plan for possible futures? And how can Oxfam and other aid organisations leverage social media to engage and empower young people, and facilitate for interaction between disparate youth groups? In a series of upcoming blogposts, we will further unpack these questions, and investigate some of the key findings from this research which has yielded interesting and sometimes surprising results.

Acknowledgements

The data for this blog was generated from the project Social Media and the Crisis of Urban Inequality: Transnational analyses of Humanitarian Responses across the Middle East, South Asia and Africa with Dr Romola Sanyal as PI, Action Aid India, Triangle Lebanon, and Urban-A as Co-Is. The work on the project was made possible with support from the Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity programme, administered by the International Inequalities Institute of the London School of Economics and Political Science.