About LSE

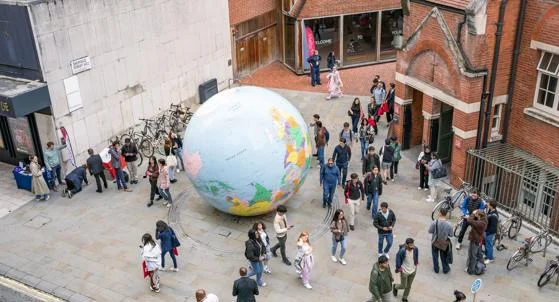

Welcome to the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), a world-leading university, specialising in social sciences. LSE was ranked top in the UK for 2025 and 2026 by the Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide. Based in the heart of London, we are a global community of people and ideas that transform the world.

Our top news

Celebrating LSE's 130th anniversary

Since 1895, the London School of Economics has shaped society and driven global change. Join us as we celebrate 130 years of LSE’s impact and enduring legacy.

LSE named as top university in the UK

The Times and The Sunday Times Good University Guide 2026 has ranked LSE as the number one university in the country

LSE academic Philippe Aghion awarded Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

He was awarded the prize for work on innovation-driven economic growth.

Introducing LSE

Pioneering people from 1895 to today

Introducing LSE

LSE was founded by social reformers in 1895 for "the betterment of society" and has been shaping the world ever since

Five global challenges at LSE

LSE, a world-leading social sciences university, is uniquely placed to help society navigate five major challenges the world is facing

League tables and rankings

LSE is ranked first in the UK and in London

LSE named as top university in the UK

The Times and The Sunday Times Good University Guide 2026 has ranked LSE as the number one university in the country

LSE leads in entrepreneurship, public engagement and professional development

The latest Knowledge Exchange Framework highlights LSE strengths in key areas

Awards and honours

Recent achievements at LSE

LSE academic Philippe Aghion awarded Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

He was awarded the prize for work on innovation-driven economic growth.

2026 New Year Honours for LSE academics

LSE academics Professor Tony Travers and Professor Jonathan Wadsworth are recognised in the 2026 New Year Honours for their impact on public service and economics.

Our strategic priorities

Education and Student Experience

Browse education news, hear from our students and explore all that LSE offers

LSE Research

Browse research news, blogs and films, search our repository of publications, or find a social science expert in your area of interest.

LSE 2030

Our strategy to shape the world