(This article is from 2017)

Did the moon landing really happen? Who killed John F Kennedy? Are Jay-Z and Beyoncé members of the Illuminati?

Conspiracy theories are not a new phenomenon – they have likely been around for as long as humans have lived in complex societies. Yet their contemporary prominence in news and public discourse – where conspiracy theories are disparaged and their believers are negatively stereotyped - is relatively unprecedented. Given this rise in prominence, Bradley Franks’ research on the worldview of conspiracy theorists offers particularly relevant insight. Working with Adrian Bangerter (University of Neuchatel), Martin Bauer, Matthew Hall, and Mark Noort (all associated with our department), Franks sought to understand this conspiratorial worldview by analysing media documents and field observations and conducting interviews with people who believe in conspiracy theories (not an easy task, since universities like LSE are often seen as key players in conspiracies). This is the first systematic attempt to understand conspiracy theories (CTs) by engaging the perspective of those who believe them: so, are CT believers really paranoid, cynical, asocial and politically disengaged, as the stereotype suggests?

Before diving into the perspective of conspiracy theorists, it’s important to note where these beliefs come from. Researchers have previously found that belief in CTs follows disturbing cultural events or collective traumas. CTs are basically a coping mechanism. They’re one way that we make sense of upsetting events. Everything from 9/11 or the death of Princess Diana have spurred conspiracy theories as people attempt to cope with and understand them. These alternative explanations for what happened are comforting because they take a complex and disturbing situation and reduce it to the actions of a conspirator behind the scenes.

This understanding of CTs also includes an idea called “monologicality”, which means that belief in one conspiracy theory predicts beliefs in many others. So if you believe that the moon landing was faked, this idea implies that you probably believe that someone besides Lee Harvey Oswald killed JFK. Overall, this idea implies that our beliefs function as a sort of network which supports and bolsters each other and ultimately help us feel like we understand society. This would mean that belief in conspiracy theories has more to do with the perspective or worldview of someone than the details of the CT itself.

…Which brings us back to Franks’ research: the conspiratorial worldview. Franks and the other researchers identified five key themes in CT-believers’ talk that combine to build a conspiratorial worldview:

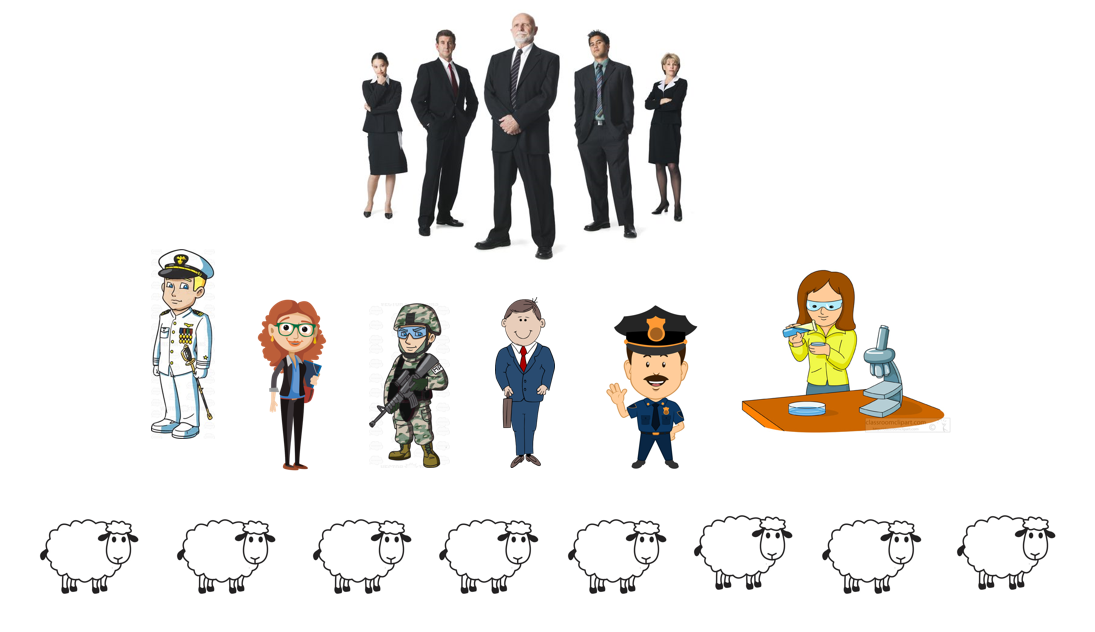

First the outgroup – the other people that CT believes defines themselves in comparison or even opposition to. Franks’ work found that CT believers’ outgroup is organised into three hierarchical groups who are all either involved or complacent in the conspiracy:

-

“Sheep”: these are the masses of people who take the news and official narratives to be the truth.

-

“Middle management”: these are the visible and accessible people who are a part of larger groups who occupy positions of power and expertise, such as police, politicians, universities, the military, scientists, etc. They control the “sheep” (keeping them “sedated”), but answer to the third group, the “evil elites”.

-

“Evil elites”: this last group have true power, which they exercise behind the scenes, and can include government agency, such as MI6 and the CIA, as well as multinational corporations, royalty, specific ethnic groups, and even reptilian aliens.

The self, as CT believers conceive of it, is on a journey of discovery or even enlightenment, with different individuals identifying themselves at different phases of the journey, but all seeing themselves as “truth seekers” (they resist being called “conspiracy theorists”). The importance of the ingroup shows that CT believers are not antisocial loners: they come together with like-minded people on a similar truth-seeking journey, as well as deferring to key “CT heroes” - fearless seekers after and proclaimers of the truth (e.g., Alex Jones, David Icke), who often use alternative media for their proclamations

Between the outgroup, the ingroup, and the self, we have the actors of this worldview. Franks and the other researchers also identified the action central to this worldview. Ingroup members occasionally engage in coordinated political actions, such as protests, joining a commune, meet up groups, etc. Since this ingroup often overlaps with other communities, such as hackers or the Occupy movement, those related political or social actions contribute to this sense of agency and activity.

The last aspect of this worldview is their vision of the future, which includes radical change and the downfall of the evil elites. This last idea brings it all full-circle. The idea of a conspiracy theory is comforting because the worldview that supports and accepts the CT also involves belief in change, in resolution of the societal problem. CT believers see themselves, and especially their ingroup, as a fundamental part of the positive change in the world, again helping to resolve the fundamental unease that sparked this way of thinking. So CT believers are not cynically disengaged from politics, but aiming towards future change.

Franks and colleagues also found that not everyone who believes in CTs does so in the same way. Some people think they are a bit of fun, others just doubt the truth of one official explanation (such as what really happened on 9/11). Others actively believe a particular CT explanation (such as that it was a CIA plot). Still others believe many CTs at once (9/11, the murder of JFK and the death of Princess Diana are all CIA plots, which themselves connect to other plots by financial and pharmaceutical companies). And still others believe in many CTs at once, but think of them as controlled not by the CIA and their like, but by extraterrestrials, lizard beings or even quantum-like energies or dimensions. So not everyone who believes in CTs is monological. The journey to increasingly complex versions of the CT worldview can function as a quasi-religious “conversion” process.

Ultimately, this work from Franks and his colleagues is ground-breaking because of its methodology and topic, but also its key finding. By understanding CT worldviews from the perspective of those who believe them, it demonstrates their internal logic and shows that CT believers do not conform to the popular stereotype of being paranoid, cynical, asocial and politically disengaged.

This summary is based on this academic article:

Franks, B., Bangerter, A., Bauer, M.W., Hall, M. and Noort, M. C. (2017). Beyond “Monologicality”? Exploring Conspiracist Worldviews. Frontiers in Psychology, 8:861. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00861