The New Politics of Inequality: How It Works - and Fails - in America

I have been working with Dr Llyod Gruber to look at spatial distributions of American partisanship, particularly the ‘clustering’ and solidification of extreme electoral outcomes in certain congressional districts. Where inequality exists, clustering processes are something of an inevitability. The past decades of globalization have accelerated these processes—and their corresponding electoral impacts—to the point where, by the 2016 election, many of the ‘safest’ congressional districts were held by the most extreme members.

Faculty: Lloyd Gruber, Department of International Development

US Centre Research Assistant: Colin Vanelli, Department of International History

Author

Colin Vanelli

LSE International History

I am immensely thankful to the US Centre for their support and for making these opportunities available for myself and for other students.

Dr Gruber’s forthcoming book project proposes that ‘big swinging districts’, which are sufficiently large to encompass multiple competing extreme ‘clusters’, can ameliorate electoral incentives towards extremism and produce relatively more stable electoral outcomes. My job has been to interrogate these claims on a theoretical level, working with the latest field research and models to help develop a solid theoretical model for analysis.

Methodology

My work has largely been in the tradition of a literature review – reading and synthesizing the latest scholarship on partisanship, political geography, and globalization to contribute theoretical depth to Dr Gruber’s model. I have also worked to develop comparative case studies which can elucidate useful findings for the US context, looking at how other electoral systems channel inequality into more productive equity-promoting policy outcomes and thinking through how these lessons can be implemented through policy reform.

Research and some findings

My research focused on a couple key areas. First, the ‘sorting’ mechanisms by which certain neighborhoods and congressional districts tend towards increasingly extreme political outcomes, largely resulting from globalization and broader political-economy influences. These factors combined with America’s unique mechanism for allotting congressional seats (on a local rather than proportional basis) suggest that growing inequality and deepening globalization should produce extremism as an increasingly common structural factor in American politics. As Dr Gruber’s research has shown, this has substantial negative impacts for policy outcomes, because extreme politicians in secure seats face less incentives to compromise on policy positions or to contribute to bi-partisan legislation. As a counterpoint, I examined data and analysis from a number of comparable international contexts, where large electoral districts (sometimes whole-country districts) produce more stable, less polarized policy environments and a more productive tendency towards inequality-addressing measures. While I found the causal mechanism between district size and policy outcomes to be murky, Dr Gruber’s explanation appears to be promising because it overcomes traditionally implicit assumptions about the distribution of economic activity. I found substantial evidence to suggest that congressional districts more exposed to foreign imports disproportionately removed moderate politicians from office in the past few decades, essentially suggesting that districts which are more exposed to globalization-linked industry are disproportionately likely to elect more-extreme politicians. In Dr Gruber’s model, then, ‘big swinging districts’ are likely to encompass entire local economies, resulting in more dynamic electoral competition which is less directly connected to specific industrial processes.

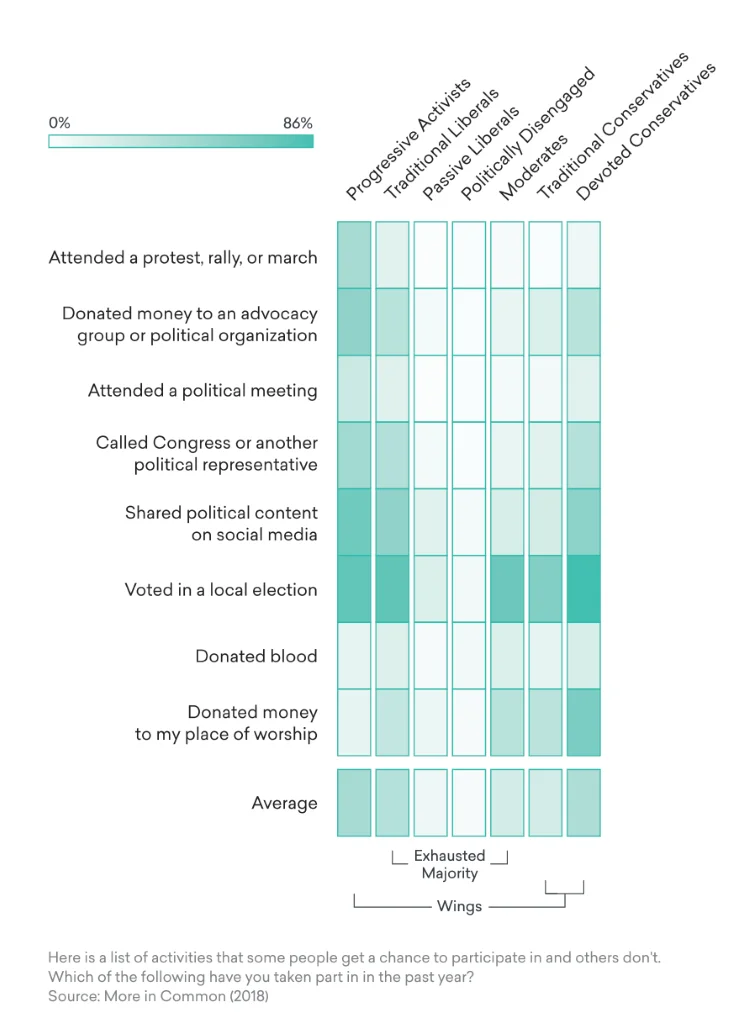

Up to this point, most research has assumed that the tendency towards extreme outcomes means that the median voter in given districts have shifted towards an extreme. However, my aggregation of field research has demonstrated a potential alternative influence: that median voters in polarized districts are increasingly unlikely to vote. In such situations, where the political middle ‘falls out’, political outcomes arise where congressional representation is both unrepresentative of the whole (measured by the median voter’s opinions) but, at the same, ‘secure’ in the sense that they do not face meaningful electoral challengers. The sources of this ‘falling out’ are multiple, but there is evidence that expanding congressional districts—and, as a result, making individual elections more competitive—could counteract the sort of voter apathy which seems to emerge in districts that are increasingly uncompetitive.

Figure 1: The so-called ‘exhausted majority’ is increasingly unlikely to participate in political processes, including voting. (Hawkins et al. "Hidden Tribes: A Study of America's Polarized Landscape" 2018)

This project was part of ongoing work, which will continue to develop during the 2020 election and beyond. As electoral reform is being taken increasingly seriously in the United States, this work fits into ongoing discussions on how to restore political engagement, while at the same time promoting productive policy environments and dynamic political competition throughout the country.

My Personal Experience

On a personal level, I enjoyed working with Dr Gruber immensely. It has been fascinating to experience how academic projects such as these develop and work their way onto paper. I have very much enjoyed engaging with the latest work in the field and benefiting from Dr Gruber’s support and unique mind for big-picture public policy. I am immensely thankful to the US Centre, particularly Saaga and Ade, for their support and for making these opportunities available for myself and for other students.

Please note that this report gives the views and findings of the Undergraduate Research Assistant, and may not necessarily reflect those of their faculty supervisor, the US Centre or the London School of Economics.