Bonds of freedom: the long fight beyond abolition

Contents

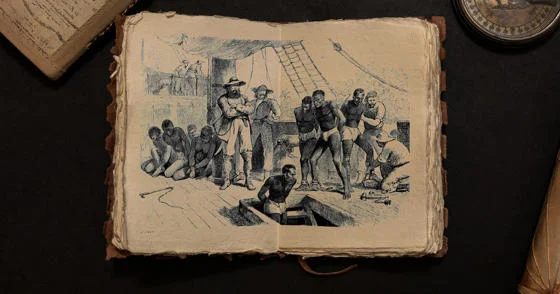

The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act 1807 marked a moment important in name only for the approximately three million people - almost a quarter of the entire transatlantic trade - trafficked across the Atlantic after this date. Following the Act, the suppression of slaving ships left many enslaved Africans in a state of limbo throughout much of the 19th century, as a tangle of international treaties complicated the concept of freedom and a network of courts, spread across colonies and slave societies, was tasked with ruling on the legality of each capture.

As liberated Africans found themselves entered into bonded labour for periods of up to 14 years, a narrative emerges of people forced to petition for their freedom, as well as setting up systems of living that worked for them as they navigated and created their own versions of freedom in the countries they arrived in.

Abolition and its afterlives

Jake Subryan Richards, Assistant Professor in the Department of International History at LSE, recounts the story of the long fight for freedom of African captives rescued from the illegal slave trade in his new book, The Bonds of Freedom: liberated Africans and the end of the slave trade. Dr Richards travelled to 14 archives across four continents to produce a meticulously researched work, highlighting the forgotten story of people seized from slave ships by maritime patrols, “liberated”, then forced into bonded labour between 1807 and 1880.

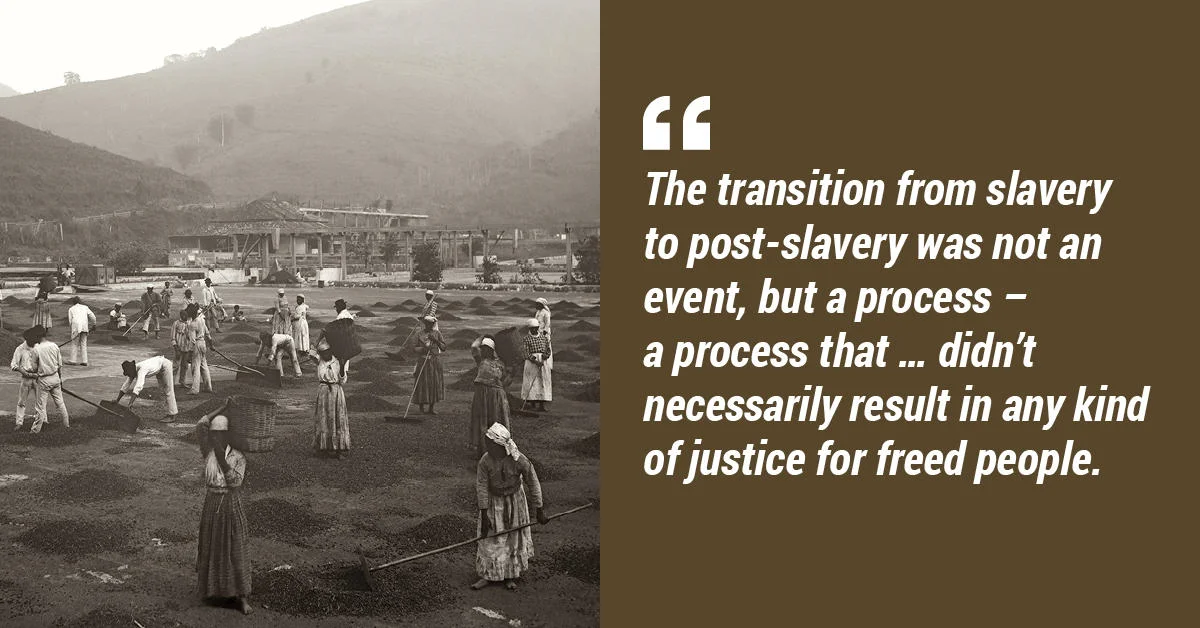

Dr Richards explains his motivation to work in this area: “The transition from slavery to post-slavery was not an event, but a process – a process that took a long time to unfold. The process didn’t necessarily result in any kind of justice for freed people who had to fight for any kind of improvement in their situation. I wanted to contribute to the understanding of slavery and emancipation in the 19th century.

“What abolition entailed in practice was a series of challenges and iniquities. The liberated Africans were denied full freedom and instead had to fight to survive forced labour that the law subjected them to. They had to petition to get their freedom from forced labour and prove how long they had worked. Even after this ordeal they weren’t given rights as citizens or rights to property. Many of these stories don’t follow a neat heroic narrative and get forgotten. I’d like my book to be part of changing this conversation.”

Petitioning for personhood: Librada’s story

One of the human stories highlighted in Bonds of Freedom is that of Librada, a woman who was trafficked to Cuba and given a Spanish name – her birth name is unknown. Archival research by Dr Richards reveals that Librada petitioned for the freedom of both herself and her son, Alfredo, who was born in Cuba. As the child of a liberated African, Alfredo was in theory born free, but Librada had no paperwork to prove his status. Without legal proof of their free status, children were vulnerable to kidnapping. For this reason, mothers were one of the first groups of liberated Africans to begin the process of petitioning for their free status to be recognised by law.

Research across four continents

The story of Librada and Alfredo is just one such story uncovered by Dr Richards as part of his extensive research across Europe, Africa, North and South America and the Caribbean. Particularly valuable sources emerged in Brazil, Sierra Leone and Cuba, and Dr Richards acknowledges the importance of the archives and the archivists themselves in helping him to assemble his research:

“One of the real achievements of modernity is the principle of free public access to the past in many countries. The archivists are incredibly knowledgeable about the records they had. A lot of the materials are uncatalogued in archives, so sometimes I was having to say to archivists, ‘I know some freed people worked in building the first public prison in Brazil,’ or ‘I know some of these liberated Africans were re-enslaved outside Sierra Leone and had to be rescued again. What happened to them?’ And they would guide me to different places I could look, or different materials I could order to see if I could find records. The local archivists I met were incredibly generous.”

Naval crews and also private ships, known as privateers, were offered the opportunity to win prize money if they captured slaving ships.

The economics of "freedom"

As Dr Richards discovered, people who were liberated from slave ships ended up spread across multiple countries and continents. Despite being located across the world in this manner what most of the liberated Africans found they still had in common was that their rights and freedoms were very far from what they might have expected as “free” men and women.

The system of prize law, which prior to 1807 had existed as part of warmaking at sea in order to financially reward those who captured a ship and its cargo, was now adapted to suppress the slave trade.

“Naval crews and also private ships, known as privateers, were offered the opportunity to win prize money if they captured slaving ships and brought them to a port where a court could decide if that capture was lawful. In doing so, they received money for the value of the ship and also the value of the cargo, and that included the human cargo, that being the captive people,” explains Dr Richards.

“That positioned the captive people as being exchangeable for money, and then also being in the position of having to earn their freedom by working for the people who liberated them. This created a tension between a system of abolition, as freeing people from slaving ships on the one hand, and subjecting them to new forms of control and of bonded labour, on the other.”

Bonded labour took many forms throughout the numerous countries where liberated Africans settled. Some plantation owners were able to request workers directly from the judges who presided over court cases on lawful capture of ships. As part of the British Empire and Spanish Empire, some enslaved people were offered the opportunity for manumission and land rights in exchange for fighting for these Empires against rebels – land rights that often did not materialise in the way that they were promised: “Empires came up with lots of legal systems for managing the exit of people from slavery into new forms of control that came with lots of duties and not the kind of rights that we would associate with freedom.”

Aside from work on plantations and fighting for Empires, other bonded labour included liberated Africans working on major infrastructure projects such as the Arsenal da Marinha and the Casa de Correção, the first public prison, both in Rio de Janeiro. Others worked on the railway running out of Havana towards the sugar plantations, allowing expansion of sugar exports from Cuba and in turn, deepening the reliance on slave labour. This railway also became a site of resistance where workers organised and launched an attack, fully aware of the significant damage such an action would inflict on the sugar industry.

Beyond “liberation”: practices of freedom and building new lives

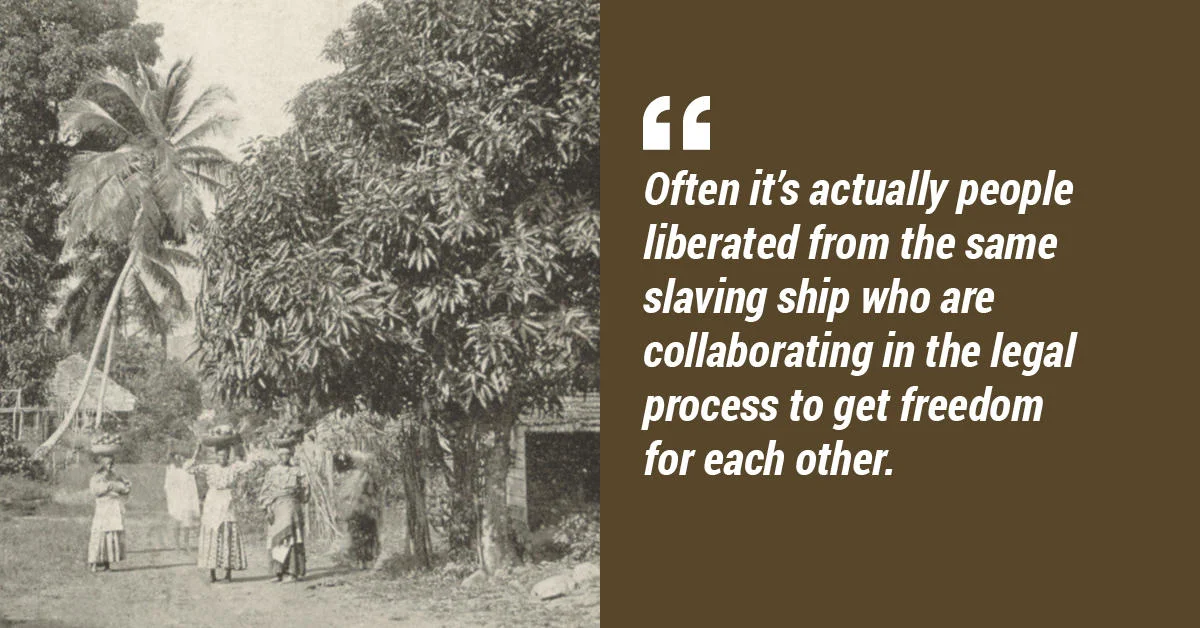

The records kept in archives serve not only to show where enslaved Africans settled and the types of work they did, but also how people grouped together to petition for freedom and begin to shape their lives in these new countries by establishing their own businesses.

“I looked at individual petitions and what I found from looking at the dating and language on them was striking. Initially, it looked like three or four petitions by individual people, but when you look at them together you find that actually it’s three or four people collaborating together. They’re often petitioning on the same day and using the same language to mutually corroborate each other’s claim to freedom. I found that often it’s actually people liberated from the same slaving ship who are collaborating in the legal process to get freedom for each other. The shipmate relationship is a very important bond these people shared.”

Dr Richards also found he could build a picture of what liberated Africans were aiming to achieve by uncovering papers showing they were partnering to set up mutual credit associations that would be recognised in law in order to lend each other money to create their own businesses which included selling food in the markets of Rio or farming outside Freetown. “These become the kinds of ways in which people make freedom meaningful in their own lives.”

As liberated Africans navigated complicated legal systems of gaining and protecting their freedom, sometimes involving capture, freedom and recapture, and navigating bonded labour, many stories emerge of people creating their own future and visions of political power both individually and together as shipmates across continents, creating a globally connected story.

“The afterlives of slavery are not just national stories. History is interlinked and can’t be separated, and to see that connection across the Atlantic, across the globe, is an important point of remembering why history matters.”

Dr Jake Subryan Richards was speaking to Helen Flood, Media Relations Officer at LSE.

Banner image: Lela Harris