Rise of Egyptian cotton market tripled rural slave population between 1848-68

Contents

When the American Civil War (1861–1865) led to a global cotton shortage, Egypt began to emerge – along with India and Brazil – as a major cotton producer. Although it was India that replaced the United States as the world’s top producer, Egypt’s cotton was prized because of its superior quality. The long fibres of the variety of cotton grown in Egypt were closer in quality to US cotton than the “short staple” variety grown in India.

The Nile Delta with its fertile and year-long irrigated soil provides ideal growing conditions for cotton. Crucially, Egypt was also able to supply the other essential ingredient to farm the crop — labour. The gruelling work of growing and harvesting the crop could be fulfilled through both slavery and the lesser-known system of state coercion of local labour.

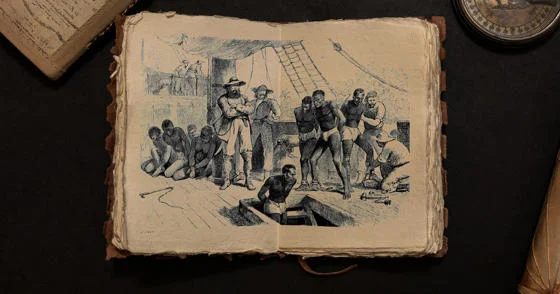

Slavery had been a long-standing medieval institution in Egypt, with black slaves being transported in caravans via trans-Saharan land routes and then sold competitively on the open market. About 94 per cent of slaves were black and from the Nilotic Sudan – which includes current day Sudan and South Sudan and extends to Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. The trans-Saharan slave trade was distinct from its transatlantic cousin which relied mainly on slaves from western and central sub-Saharan Africa.

These population censuses are unique because they are the earliest precolonial censuses from a non-Western country to include information about every household member.

Dr Mohamed Saleh, Associate Professor of Economic History at LSE, explains: “The trans-Saharan slave trade was far smaller than the transatlantic slave trade, but it was a much older institution and persisted for longer.”

The other coercive system of labour in Egypt was state coercion which forced peasants to work through violence and intimidation.

Egyptian cotton trade relied on slave and state coerced labour

Dr Saleh has investigated the impact of Egypt’s cotton boom on these two types of labour. As part of his research he digitised, for the first time, two nationally representative samples of the Egyptian population censuses of 1848 and 1868 from the original Arabic manuscripts at the National Archives of Egypt. These allow a comparison of the rural labour force before and during the cotton boom.

Dr Saleh explained, “These population censuses are unique because they are the earliest precolonial censuses from a non-Western country to include information about every household member. They enumerate not only men, but also women, children and importantly for my research, slaves.

“They are also the only surviving individual level record of the slave population in Egypt, and possibly the Middle East.

“In the United States the first census that provided information at the individual level took place in 1850.”

Dr Saleh’s research reveals that while the majority of Egypt’s rural labour force prior to the cotton boom, in 1848, were self-employed peasants (51 per cent) and wage agricultural labourers (10 per cent), eight per cent were subject to coercion. Rural slavery was rarer, with slaves constituting one per cent of the population in 1848.

However, the cotton boom caused the number of slaves to surge, with the rural slave population tripling between 1848 and 1868, from 39,762 to 144,592, to make up three per cent of the rural workforce.

Middle class landowners relied on slaves rather than coercive labour because they did not have access to the tools of state violence.

Middle class landowners fuelled use of slave labour

Interestingly, the rising demand for slaves came from the rural middle class – village headmen from areas outside large estates — rather than from the landed elite. In contrast the elite met their demands for labour through the coercion of local peasants.

“Middle class landowners relied on slaves rather than coercive labour because they did not have access to the tools of state violence,” says Dr Saleh. However, they did have access to money, so they could afford to purchase imported slaves on the open market.”

Dr Saleh’s work shows how the two institutions of state coercion and slavery reinforced one another. In areas where there was more state coercion of the peasantry, there was also a higher demand for slaves among the rural middle classes.

“If you have a fixed amount of people available for labour in your village and then the state comes in and takes many of them out of the labour market by coercing them to work on the landed elites’ estates, then you have fewer workers to recruit. This is how state coercion increased the demand for slaves,” explains Dr Saleh.

The trans-Saharan slave trade ended in 1877 when, under pressure because the country had defaulted on its international debt, a weakened Isma'il Pasha, the Khedive or ruler of Egypt, acquiesced to the demands of the British Abolitionists.

Abolitionists ended slavery but were not aware of state coerced labour

However, forced labour in Egypt did not end with the end of slavery. British Abolitionists, familiar with the transatlantic slave trade, had little knowledge about state coercion of the local peasantry because it was a localised institution that existed in the Middle East and was more subtle than the slave trade.

“The abolitionists in Britain, and Europe more generally, were focused on abolishing the trans-Saharan slave trade because of their work on and familiarity with the transatlantic slave trade. This meant that they didn’t pay much attention to the coercion of the locals,” says Dr Saleh.

“I think one implication here is that you need local expertise to understand what institutions are significant in their context. In terms of magnitude the local coercion of local peasantry was far larger than slavery.”

But state coercion did not increase after abolition, as might have been expected.

“In fact, Egyptian parliamentary minutes show that rural middle-class Members of Parliament started to become more critical of state coercion in the wake of abolition.” says Dr Saleh. “This is not because they were necessarily progressive, but because they didn’t like the fact that the landed elite had a complete monopoly over the coercion of state locals. They wanted access to local labour and that’s why they pushed against state coercion.

“Indeed, abolition had the effect of raising agricultural wages as the demand for wage labourers increased among the rural middle class, and the ex-slaves workforce gradually disappeared.”

Mohamed Saleh was speaking to Sue Windebank, Senior Media Relations Manager at LSE.

Download a PDF version of this article