How the model of apprenticeship helped to reshape the English economy

Contents

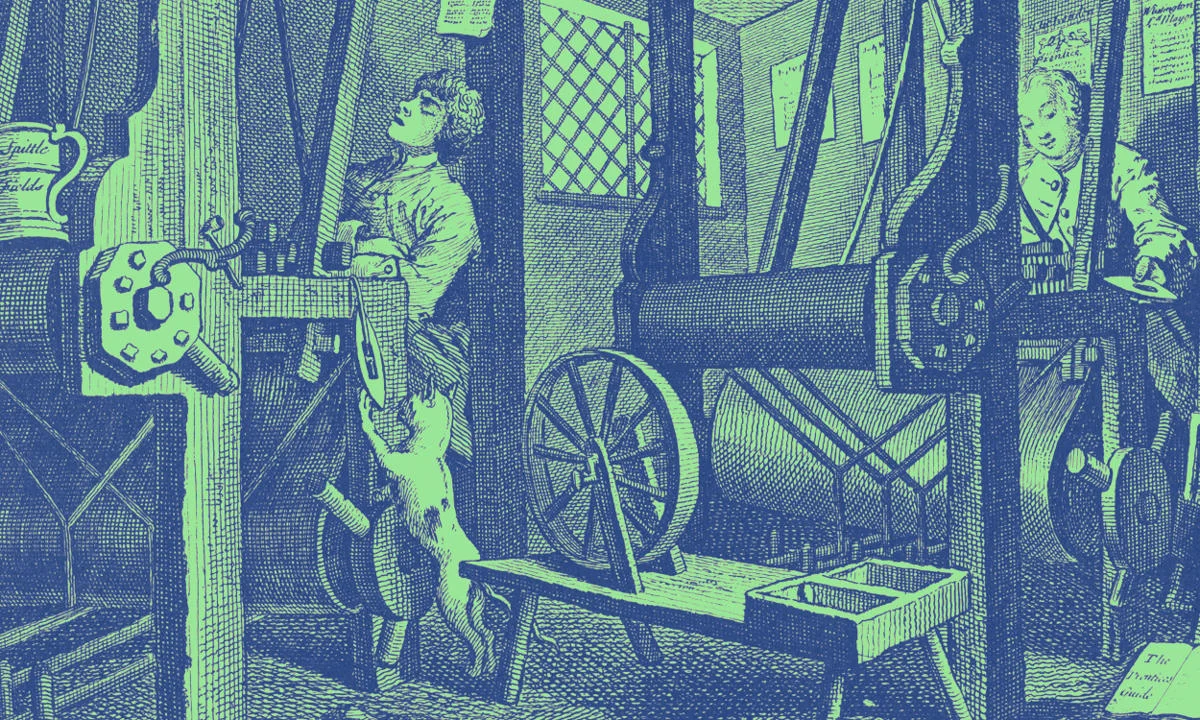

In premodern England, a series of profound transformations dramatically changed the location of the workforce from countryside to cities and the nature of work from agriculture to skilled trades and industry. These shifts resulted in a sharp rise in GDP per capita and set the stage for industrialisation, the expansion of the empire and the modern economy that followed. At the heart of this upheaval was the apprenticeship system.

From farm to city: a workforce on the move

Between 1550 and 1750, the workforce in premodern England experienced a marked change in the numbers of workers moving away from agricultural work in rural areas and towards manufacturing work in cities. Patrick Wallis, a professor in the Department of Economic History at LSE and author of The Market for Skill: apprenticeship and economic growth in early modern England, presented the significant role apprenticeships played in this transformation, and what this meant for both the apprentices and the masters, at a recent Research Showcase event.

“The challenge of this premodern growth is not inconsiderable. It means moving people out of agriculture into industry and services so they're not doing the jobs that their parents once did. It means moving workers from the countryside into the cities by the tens of thousands, and it means spreading new techniques and new ways of working so that people have to share the intellectual property rather than keep it locked into a particular family or firm,” he explained.

![[At this time] the apprenticeship system was dominated by London, with three quarters of these workers undertaking their training in the capital.](/all-images/apprenticeships-industrial-revolution-1200-x-6283.x0772abba.jpg?w=1200&h=628&q=85&f=webp)

Three ways apprenticeships transformed opportunity

Apprenticeship aided the transformation of England in numerous ways, with Professor Wallis, highlighting three distinct mechanisms in his talk. Firstly, apprenticeship formed the bridge between farming and industry, allowing workers from outside a craft or trade to acquire skills that would otherwise have been closed off to them if fathers had simply trained their sons to continue their work in farming and agriculture. Secondly, it bridged the countryside and cities by providing apprentices with a confirmed destination and housing security. Thirdly, it spread innovation by picking out the most talented masters to provide apprenticeships and training, and who spread innovative skills and new ideas to their apprentices. These apprentices went on to set up their own businesses, and perhaps take on apprentices of their own.

The story of Robert Burdett

By way of illustration, Professor Wallis introduced the audience to landowners Sir Thomas and Lady Jane Burdett of Derbyshire and their children, including their second son, Robert.

“In 1629 Robert is made an apprentice to a merchant in London called Nathan Wright who will train Robert for the next seven years . . . they have no connection to Nathan Wright but they know that they can find a good master. Wright will become an incredible success as one of the directors of the East India Company and Robert becomes a leading merchant in London so he achieves the movement from land to trade, from countryside to city.”

Professor Wallis went on to explain that had Robert not been a natural fit for the position of merchant both Robert and Nathan could have chosen to end the apprenticeship early, with Robert returning to his family home and a position on their farm. Happily, for both parties, that was not the case on this occasion.

The Burdett family were particularly well-to-do, but Professor Wallis’s research shows that new apprentices came from all social classes, from gentry to farm labourers from all over England.

In researching this topic, Professor Wallis explored the records of 750,000 apprentices to identify distinct patterns and trends. He found that the apprenticeship system was dominated by London, with three quarters of these workers undertaking their training in the capital. A large share of these workers came from agriculture and from all levels from gentry to labourers, with almost all of London’s working male population involved in the system of apprenticeship at some point.

Masters of innovation

Professor Wallis’s research also led him to explore the world of the masters, and the opportunities they provided for the apprentices who trained under them. “Most of the training is in the hands of very few masters . . . fewer than 10 per cent of masters will train more than five apprentices over their career . . . Thomas Tompion, arguably Britain’s greatest watchmaker and clockmaker, trained 23 apprentices. This is a man with a lot of intellectual property and he shares it. George Graham, one of Tompion’s apprentices, trains 16.”

Contracts, incentives and freedom to leave

The apprenticeship system worked due to both institutions and incentives. As Professor Wallis sets out, the old institutions of Guilds were not central to the apprenticeship system which was at its core a labour market contract. Any suspicions that masters were looking for cheap and easy-to-find labour are debunked both by the success spread by masters and also the ease by which apprentices could leave training contracts if they desired. Indeed, one in ten contracts were adjusted or ended this way and some of the money invested could be recouped. In turn, masters could end contracts with apprentices who turned out not to have an aptitude for their craft.

There was a great incentive for young workers to serve an apprenticeship at this time as access to work in manufacturing and services was restricted, and apprenticeships provided a way in, alongside labour market rights for the worker. Additionally, starting work as an apprentice had a back-up option of returning to farm work later in life, while working in agriculture and taking up an apprenticeship as an older worker wouldn’t be.

As industry developed and larger companies began to dominate in the 19th and 20th centuries, in-demand skills moved away from highly specialised expertise to general skills such as maths and engineering, and the workforce moved on in the same way with apprenticeships being offered by these bigger companies who would expect their workers to remain with the company for many years rather than setting up on their own, reflecting the modern style of apprenticeship we know today.

This Research Showcase talk was written up by Helen Flood, Media Relations Officer at LSE.