It’s not just about the money: a reappraisal of Medieval English agricultural wages

Contents

What happens to a country’s economy when half its population dies within a few years? The Black Death did exactly this to England from 1348 to 1350, and it is a question historians have been puzzling over for more than a century. While such shocks are almost universally bad for economies in the short term, some have emphasised the plague’s positive effects on England’s long-run economic trajectory, referring to the period as a so-called "golden age" of labour.

Such views are generally based on an understanding that wages rose in the aftermath of the Black Death. However, the evidence that underpins our understanding of medieval wages is problematic. Myself and my co-authors (Dr Vincent Delabastita, Radboud University and Dr Spike Gibbs, University of Mannheim) are currently collecting new data and new methods to provide fresh insights on, not only the impacts of the Black Death, but also the long-run story of England’s historical transition to modern economic growth.

While historians have long appreciated that information on wages and standards of living are among the best evidence to explore the dynamics of preindustrial economies, recent scholarship has pushed wages to the very centre of key debates. Wage evidence has become the fulcrum upon which several grand theories, like the Little and Great Divergences - periods of socio-economic shifts in the Western world - and the "Malthusian" nature of pre-modern economies (the theory, initially put forward by Thomas Malthus in 1798, and since tested by many scholars, that the relationship between population and resources was the ultimate determinant of living standards and economic vitality) now pivot. Yet, there remains a degree of arbitrariness surrounding both the data and the assumptions that form the basis of many wage series.

In medieval England, as in most pre-modern societies, wages could be paid by the day, on an annual basis, or anywhere in between.

We can’t assume medieval labourers were always paid a "fair" wage

The specific issue that our research addresses is the fact that, in medieval England, as in most pre-modern societies, wages could be paid by the day, on an annual basis, or anywhere in between. Often, they were paid both in cash and "in-kind", usually in grain but also sometimes in accommodation, food, clothing or even tools. In medieval England, many workers received the majority of their wages as in-kind payments.

Until now, it has been very difficult to accurately estimate the value of these payments. Some studies have avoided this issue by focusing entirely on payments in-kind (as I myself did in an earlier study), which means we miss the modest (but not insignificant) proportion of wages paid in cash. Other studies concentrate on workers paid solely in cash. This, however, forces us to consider only a very narrow group of workers, usually men employed by the day in agriculture or building trades.

More recent work has been very innovative in estimating the value of in-kind payments using a Consumer Price Index (CPI) basket of goods. However, it is difficult to build accurate consumer baskets for the Middle Ages, especially if we want to study the evolution of living standards over time, as consumption patterns could change quickly and significantly.

More problematic, however, is the assumption that the value of in-kind payment provided to labourers was equivalent to the value of the requisite staples in a "respectable" CPI basket. To put it another way, using CPI baskets in this manner assumes that these labourers were always paid a "fair" or "living" wage which provided full insurance against market price fluctuations, not only for grains, but for all other items in the CPI basket as well. Historically, we know this was not the case. Many thousands starved in the Great Famine of 1316 to 1318 and the very purpose of post-plague labour legislation in 1349 and 1351 was designed to force labourers to accept wages at pre-plague rates, even though living costs had risen dramatically. Indeed, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 was at least partially motivated by long-standing dissatisfaction with 14th century labour relations.

The case of the carter and his in-kind earnings

The importance of in-kind earnings problem can be illustrated with the example of a single individual. In 1296, a carter – who made a living transporting goods on a horse-drawn cart - working for the whole year at the manor of Peasenhall, in Suffolk, was paid with a composite wage comprised of an in-kind grain "livery" and a cash payment. The carter earned 4.31 quarters (~280 litres) of maslin (a 50:50 mixture of wheat and rye) and 3 shillings (s) for a year’s work.

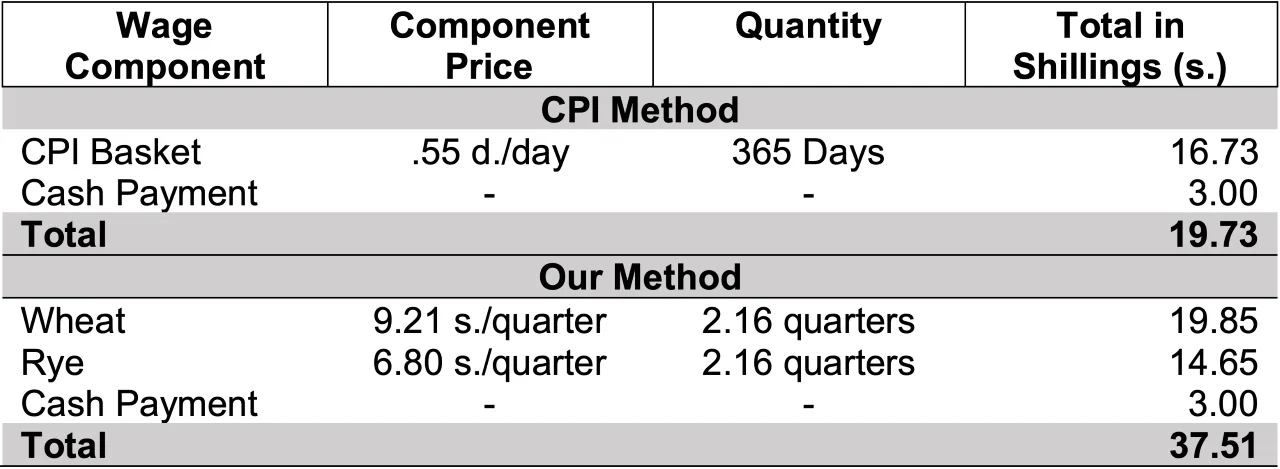

The CPI basket method assumes that the value of the in-kind portion of the wage was equivalent to the cost of a consumer price index (CPI) basket of consumables required for a respectable standard of living for one year. The cost of such a basket for that time is estimated at .55 pence (d) per day. This method yields a total annual wage of 19.73 s (.55d x 365 + 3s) for this particular carter. However, is this a truly accurate picture of the carter’s wage?

Our method takes the same 3s of cash, but instead of using the CPI estimation, adds this to the actual value of the grain paid to the labourer. The quantities and local prices are laid out clearly in the Peasenhall account and this can be compared with existing national grain-price series. This works out as follows:

Our calculations yield a total gross annual wage of 37.51 s that is 90 per cent higher than the result obtained with the CPI method.

Therefore, in our research, we apply a robust historical method where we systematically gather wage payments made to men, women and children working in medieval English agriculture. We then accurately cost the in-kind components of their wages. This facilitates the creation of a far more accurate wage series for medieval England which avoids the distorting effects of proxies like CPI baskets.

We are also exploring the economics of in-kind payments. Why, in a monetised economy, did such non-monetary payments persist for so long? Were they encouraged by a scarcity of cash, intended as insurance against volatile changes in grain prices, used by employers to circumvent the post-Black Death labour legislation, or merely a recognition of the practical reality that many servants-in-husbandry lived in? Our project, which aims to create an accurate wage series of medieval England based entirely on historical data collected both regionally and over time, will help us to answer all these questions which are central to our understanding of the massive economic and societal changes that occurred in the late Middle Ages.

Image credit: British Library Add MS 42130, fo 171v.

Download a PDF version of this article