How far should we trust the voice of AI?

Contents

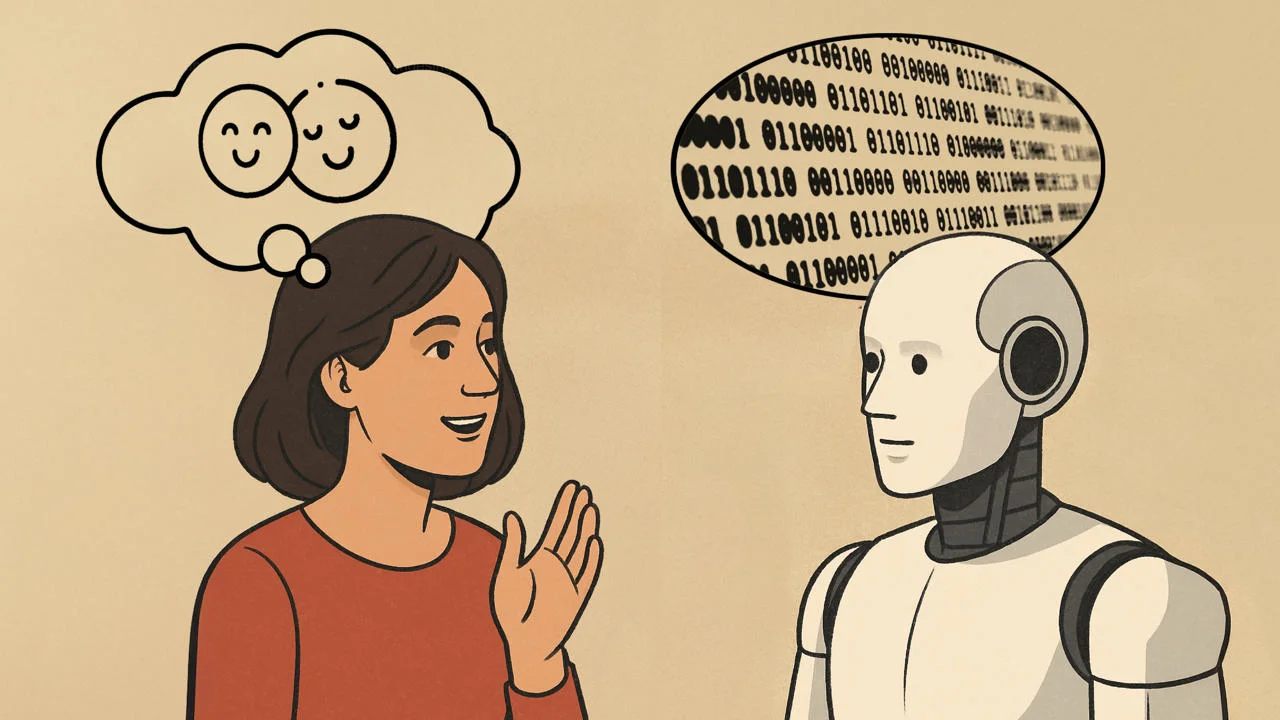

Once the stuff of science fiction, talking machines are now a part of daily life. Whether answering questions via a smart speaker or navigating us through traffic, voice-based artificial intelligence (AI) has quickly become a dominant mode of human-computer interaction.

As these voice-enabled systems grow more sophisticated, they raise a pressing question: are we starting to believe they are more intelligent, more autonomous – even more human – than they truly are?

Research led by Dr Anuschka Schmitt, Assistant Professor of Information Systems in the Department of Management at LSE, has explored this phenomenon through the lens of what academics call ‘‘agency attribution’’– our tendency to perceive machines as independent agents when they begin to sound and act like us. Her team’s paper, ‘‘The role of AI-based artifacts’ voice capabilities for agency attribution’’, was published in the Journal of the Association for Information Systems. Its findings are stark: the more natural and lifelike the voice, the more likely we are to overestimate what the system can actually do.

Dr Schmitt explains: "The latest developments enable us to have an eerily lifelike audio conversation with ChatGPT or create a realistic podcast in seconds by uploading documents to Google’s NotebookLM, so it’s technology that’s evolving very quickly.

"Reviewing previous research and real-world use cases, we observed that people were ascribing agency to voice-based systems. Even before large language models became widespread, there were clear signs that users might attribute more capability to these systems than they actually possess."

The concern is not merely philosophical. In critical environments such as healthcare or financial services, misplaced attributions to AI can have significant consequences. "Voice-based interaction creates a more natural and effortless experience," she says. "But that same naturalness can make the system appear more capable and reliable than it truly is."

Why talking feels more human - even with AI

Voice interfaces draw upon a deeply human mode of communication. "Voice is arguably the most natural and effortless modality," Dr Schmitt explains. "We usually learn to speak and listen before we read or write. The way something is said can shape our mood, influence our behaviour, and reveal personal characteristics such as emotion, identity or intent."

That power – so intuitive to human communication – is not lost on AI designers. Subtle elements, such as pitch, rhythm, pacing and even pauses, are carefully engineered to make voices sound persuasive and personable. "We spent a considerable amount of time understanding the full range of vocal cues and how they are incorporated into AI systems," she says. "It’s rarely one feature alone. Rather, it’s the combination of these that makes a voice sound convincingly human."

This phenomenon is supported by the psychological principle of stimulus generalisation: the idea that humans often apply past experiences to interpret new but similar stimuli. "If a voice sounds human, we instinctively draw on the same cognitive patterns we use in human interactions," Dr Schmitt says. "Even when we know it is a machine, we may still respond as though it were a person."

We risk placing too much trust in AI

This attribution of agency can lead to a form of overreliance on AI – especially when the system appears more intelligent or autonomous than it is. "In high-stakes scenarios, such as surgery or financial advice, we want users to develop calibrated trust," she warns. "Designing a system with a highly human-sounding voice may inadvertently cross an ethical line by fostering too much trust."

Nor is the issue purely functional. Voice-based AI can, intentionally or not, perpetuate cultural and gender-based biases. "Studies have shown that certain tasks are assigned voices according to stereotypical gender roles – male for security functions, female for domestic assistance," Dr Schmitt notes. "These are deliberate design choices with real-world implications."

The effects of such design choices vary considerably across user groups. "Individual differences – such as technological familiarity, hearing ability or cultural associations – affect how a voice is perceived," she adds. "Designers must consider these variables, not only to enhance accessibility but to avoid reinforcing social inequalities."

Ethical design of AI

So what might ethical voice design look like? One possibility is transparency: ensuring that AI systems remind users they are not human. "This could be particularly important in contexts involving vulnerable groups – children, for example, or patients receiving therapeutic support," says Dr Schmitt.

Yet the commercial pressure to create systems that feel seamless and trustworthy can discourage such disclosures. "There is no one-size-fits-all guideline," she concedes. "But designers should at least ask: is this design cue ethically desirable? Could it lead to long-term harm or misunderstanding?"

The study stops short of calling for regulatory intervention but suggests that greater awareness is needed among both developers and users.

At a time when AI systems are becoming increasingly autonomous and dialogue-based interaction more widespread, the question of how these systems communicate is becoming more urgent. "When something sounds polished, human, and intelligent, we tend to assign it credibility – even if we know the voice belongs to a machine," says Dr Schmitt.

That tendency, she argues, demands a choice. "Do we wish to design systems that prioritise appearing humanlike and trustworthy? Or should we focus on helping people think critically about what they are hearing?"

In essence, voice makes AI more accessible, but also more persuasive. Dr Schmitt’s research highlights how this power must be used wisely.

Dr Anushka Schmitt was speaking to Joanna Bale, Senior Media Relations Manager at LSE.

AI, technology and society special edition

At LSE our researchers are using technology’s revolutionary power to understand our world better, looking at AI and technology’s potential to do good, and limiting its potential to do harm.

Browse upcoming events, short films, articles and blogs on AI, technology and society on our dedicated hub.

Join us on campus or online wherever you are in the world for LSE Festival: Visions of the Future, a week of special events 16-21 June 2025, free and open to all.

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a world-leading university, specialising in social sciences and named University of the Year by the Good University Guide 2025. Based in the heart of London, we are a global community of people and ideas that transform the world.